Roman Civil War (68-69 AD)

The Year of the Four Emperors was a year in the history of the Roman Empire, AD 69, in which four emperors ruled in succession: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian.

The suicide of the Roman The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterranean Sea in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, and was ruled by emperors. The first two centuries of the Roman Empire saw a period of unprecedented stability and prosperity known as the Pax Romana ('Roman Peace'). The Empire was later ruled by multiple emperors who shared control over the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. emperor Nero in 68 was followed by a brief period of civil war, the first Roman civil war since Mark Antony's death in 30 BC. Between June of 68 and December of 69, Ancient Rome witnessed the successive rise and fall of Galba, Otho, and Vitellius until the final accession of Vespasian, first of the Imperial Flavian dynasty, in July 69. The social, military and political upheavals of the period had Empire-wide repercussions, which included the outbreak of the Revolt of the Batavi.

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterranean Sea in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, and was ruled by emperors. The first two centuries of the Roman Empire saw a period of unprecedented stability and prosperity known as the Pax Romana ('Roman Peace'). The Empire was later ruled by multiple emperors who shared control over the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. emperor Nero in 68 was followed by a brief period of civil war, the first Roman civil war since Mark Antony's death in 30 BC. Between June of 68 and December of 69, Ancient Rome witnessed the successive rise and fall of Galba, Otho, and Vitellius until the final accession of Vespasian, first of the Imperial Flavian dynasty, in July 69. The social, military and political upheavals of the period had Empire-wide repercussions, which included the outbreak of the Revolt of the Batavi.

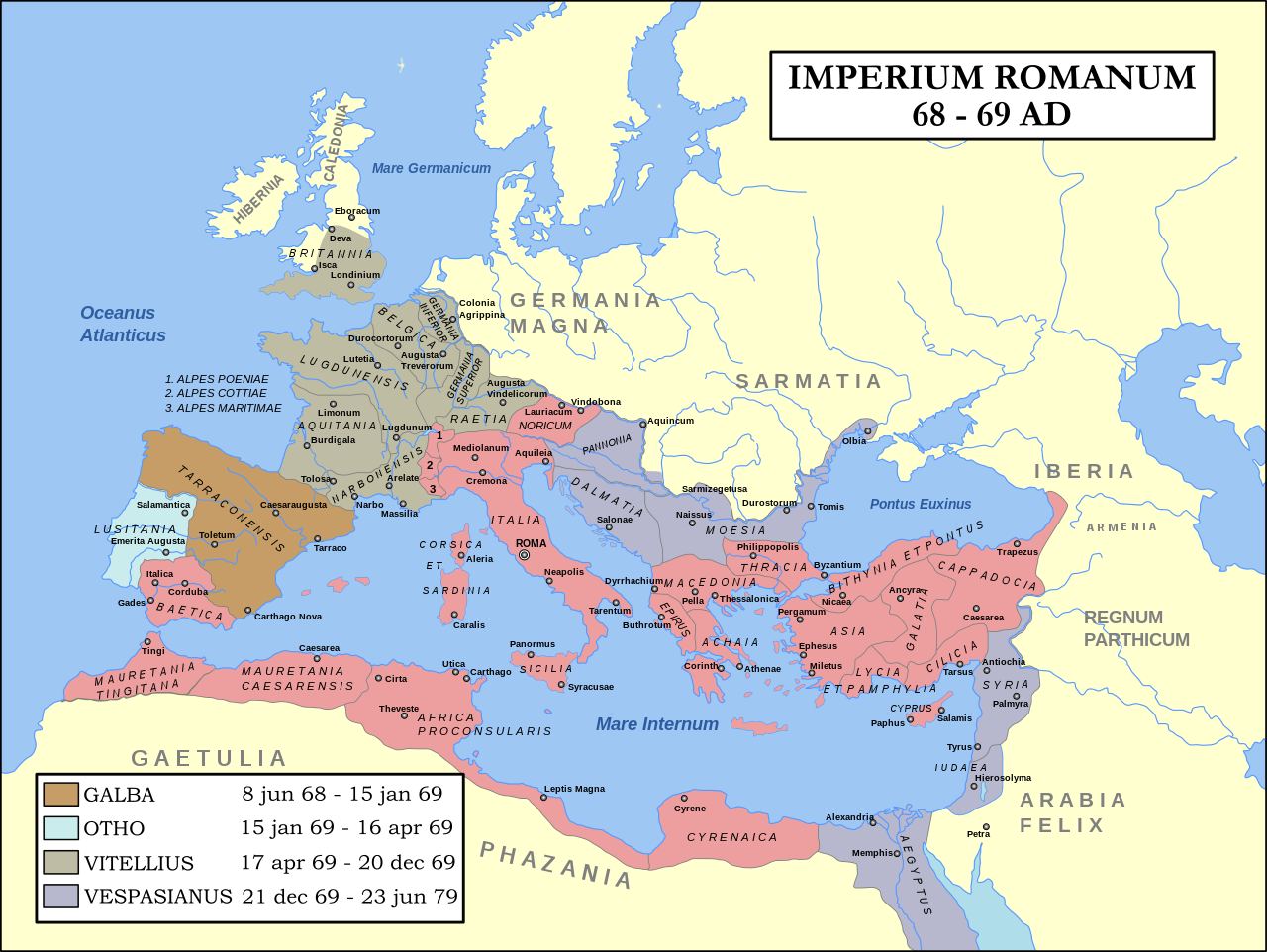

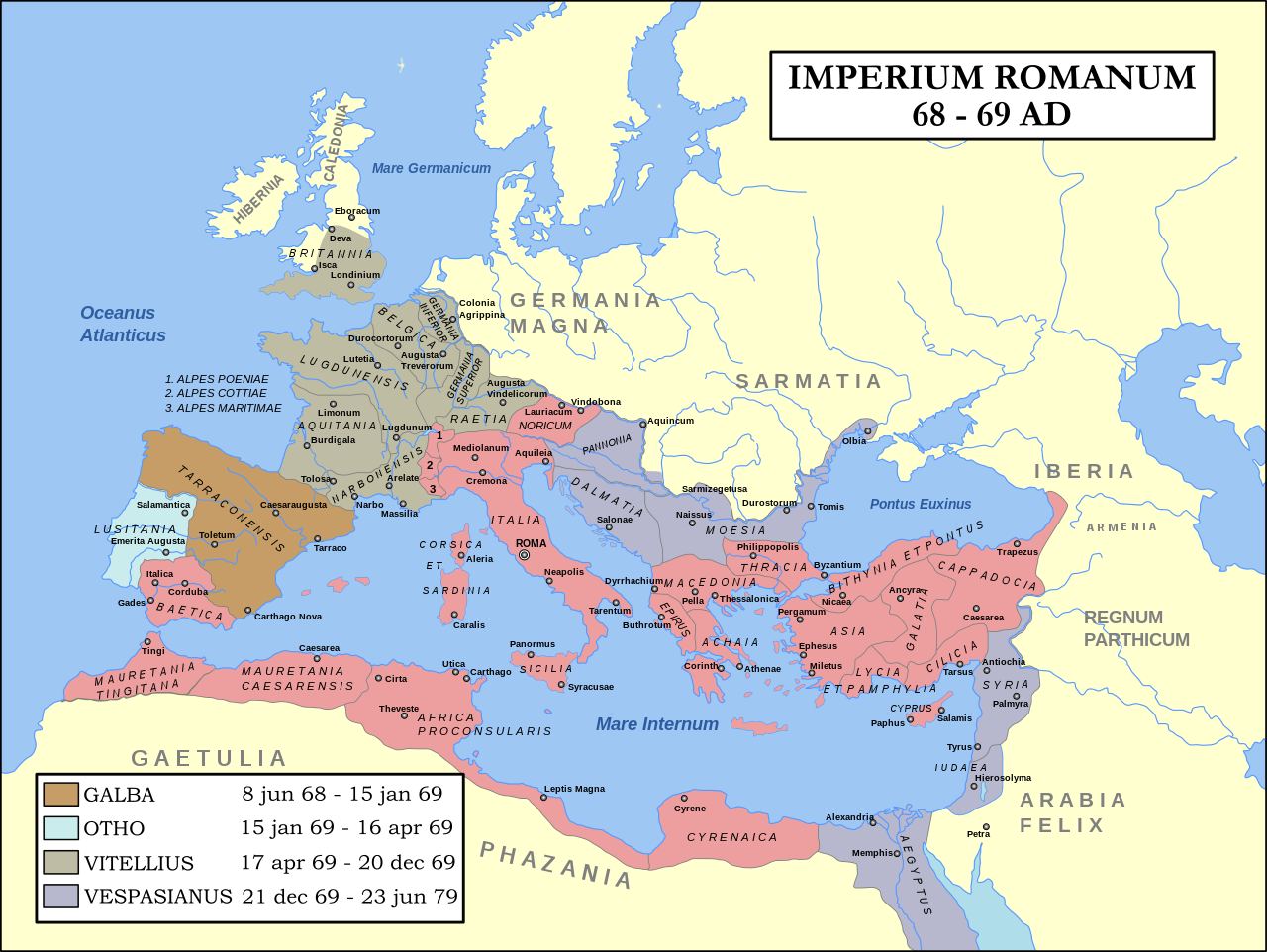

Map of the Roman Empire during 69AD, the Year of the Four Emperors. Coloured areas indicate provinces loyal to one of four warring generals

Map of the Roman Empire during 69AD, the Year of the Four Emperors. Coloured areas indicate provinces loyal to one of four warring generals.

( Click image to enlarge)

Succession

Nero to Galba

In 65, the Pisonian conspiracy attempted to restore the Republic, but failed. A number of executions followed, leaving Nero with few political allies left in the Senate. In late 67 or early 68, Caius Julius Vindex, governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, rebelled against Nero's tax policy, with the purpose of substituting Servius Sulpicius Galba, governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, for Nero.

Vindex's revolt in Gaul was unsuccessful. The legions stationed at the border to Germania marched to meet Vindex and confront him as a traitor. Led by Lucius Verginius Rufus, the Rhine army defeated Vindex in battle and Vindex killed himself. Galba was at first declared a public enemy by the Senate.

In June 68, the Praetorian Guard prefect, Nymphidius Sabinus, as part of a plot to become emperor himself, incited his men to transfer their loyalty from Nero to Galba. Nero was suddenly powerless and the Senate declared him an enemy of the state. He fled the city and committed suicide. Galba was recognized as emperor and welcomed into the city at the head of a single legion, VII Galbiana, later known as VII Gemina.

Galba to Otho

This turn of events did not give the German legions the reward for loyalty that they had expected but rather accusations of having obstructed Galba's path to the throne. Their commander, Rufus, was immediately replaced by the new emperor. Aulus Vitellius was appointed governor of Germania Inferior. The loss of political confidence in Germania's loyalty also resulted in the dismissal of the Imperial Batavian Bodyguards and rebellion.

Galba did not remain popular for long. On his march to Rome, he either destroyed or took enormous fines from towns that did not accept him immediately. In Rome, Galba cancelled all the reforms of Nero, including benefits for many important persons. Like his predecessor, Galba had a fear of conspirators and executed many senators and equites without trial. The soldiers of the Praetorian Guard were not happy either. After his safe arrival in Rome, Galba refused to pay them the rewards that the prefect Nymphidius had promised them in the new emperor's name. Moreover, at the beginning of the civil year of 69 on January 1, the legions of Germania Inferior refused to swear allegiance and obedience to Galba. On the following day, the legions acclaimed their governor Vitellius as emperor.

Hearing the news of the loss of the Rhine legions, Galba panicked. He adopted a young senator, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus, as his successor. By doing this, he offended many, above all Marcus Salvius Otho, an influential and ambitious nobleman who desired the honor for himself. Otho bribed the Praetorian Guard, already very unhappy with the emperor, winning them to his side. When Galba heard about the coup d'état, he went to the streets in an attempt to stabilize the situation. It proved a mistake, because he could not attract any supporters. Shortly afterwards, the Praetorian Guard killed him in the Forum along with Lucius.

- Otho's legions: XIII Gemina and I Adiutrix

Otho to Vitellius

The Senate recognized Otho as emperor that same day. They saluted the new emperor with relief. Although ambitious and greedy, Otho did not have a record for tyranny or cruelty and was expected to be a fair emperor. However, Otho's initial efforts to restore peace and stability were soon checked by the revelation that Vitellius had declared himself Imperator in Germania and had dispatched half of his army to march on Italy.

Vitellius had behind him the finest legions of the empire, composed of veterans of the Germanic Wars, such as I Germanica and XXI Rapax. These would prove to be the best arguments in his bid for power. Otho was not keen to begin another civil war and sent emissaries to propose a peace and convey his offer to marry Vitellius' daughter. It was too late to reason; Vitellius' generals were leading half of his army toward Italy. After a series of minor victories, Otho suffered defeat in the Battle of Bedriacum. Rather than flee and attempt a counter-attack, Otho decided to put an end to the anarchy and committed suicide. He had been emperor for a little more than three months.

- Vitellius' legions: I Germanica, V Alaudae, I Italica, XV Primigenia, I Macriana liberatrix, III Augusta, and XXI Rapax

- Otho legions: I Adiutrix

Vitellius to Vespasian

On the news of Otho's suicide, the Senate recognized Vitellius as emperor. With this recognition, Vitellius set out for Rome; however, he faced problems from the start of his reign. The city remained very skeptical when Vitellius chose the anniversary of the Battle of the Allia (in 390 BC), a day of bad auspices according to Roman superstition, to accede to the office of Pontifex Maximus.

Events seemed to prove the omens right. With the throne tightly secured, Vitellius engaged in a series of banquets (Suetonius refers to three a day: morning, afternoon, and night) and triumphal parades that drove the imperial treasury close to bankruptcy. Debts quickly accrued and money-lenders started to demand repayment. Vitellius showed his violent nature by ordering the torture and execution of those who dared to make such demands. With financial affairs in a state of calamity, Vitellius took the initiative of killing citizens who named him as their heir, often together with any co-heirs. Moreover, he engaged in the pursuit of every possible rival, inviting them to the palace with promises of power only to order their assassination.

Meanwhile, the legions stationed in the African province of Egypt and the Middle Eastern provinces of Iudaea (Judea/Palestine) and Syria acclaimed Vespasian as emperor. Vespasian had received a special command in Judaea by Nero in 67 with the task of putting down the Great Jewish Revolt. He gained the support of the governor of Syria, Gaius Licinius Mucianus. A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus. Vespasian himself travelled to Alexandria, where he was acclaimed emperor on July 1, thereby gaining control of the vital grain supplies from Egypt. His son Titus remained in Judaea to deal with the Jewish rebellion. Before the eastern legions could reach Rome, the Danubian legions of the provinces of Raetia and Moesia also acclaimed Vespasian as Emperor in August, and led by Marcus Antonius Primus invaded Italy. In October, the forces led by Primus won a crushing victory over Vitellius's army at the Second Battle of Bedriacum.

Surrounded by enemies, Vitellius made a last attempt to win the city to his side, distributing bribes and promises of power where needed. He tried to levy by force several allied tribes, such as the Batavians, but they refused. The Danube army was now very near Rome. Realizing the immediate threat, Vitellius made a last attempt to gain time by sending emissaries, accompanied by Vestal Virgins, to negotiate a truce and start peace talks. The following day, messengers arrived with news that the enemy was at the gates of the city. Vitellius went into hiding and prepared to flee, but decided on one last visit to the palace, where Vespasian's men caught and killed him. In seizing the capital, they burned down the temple of Jupiter.

The Senate acknowledged Vespasian as emperor on the following day. It was December 21, 69, the year that had begun with Galba on the throne.

- Vitellius legions: XV Primigenia

- Vespasian legions: III Augusta, I Macriana liberatrix

Vespasian met no direct threat to his imperial power after the death of Vitellius. He became the founder of the stable Flavian dynasty that succeeded the Julio-Claudians. He died of natural causes in 79. The Flavians, each in turn, ruled from 69 to 96.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Year of the Four Emperors", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.