World War I (1914-1918)

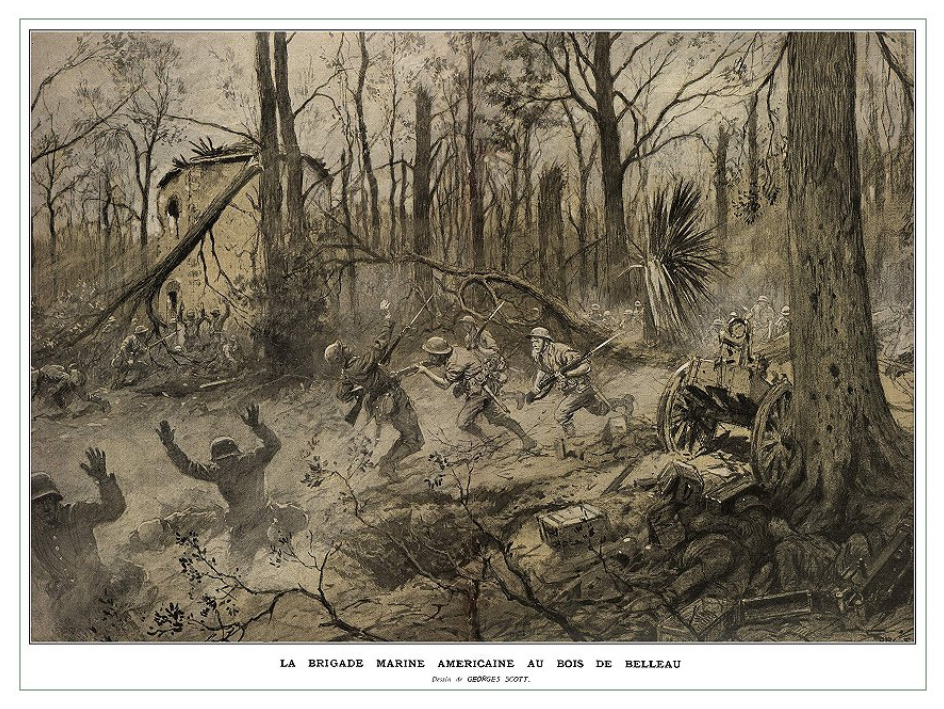

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun (Bataille de Verdun), fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916, was the largest and longest battle of the First World War on the Western Front between the German and French armies. The battle took place on the hills north of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France. The German 5th Army attacked the defences of the Fortified Region of Verdun (RFV, Région Fortifiée de Verdun) and those of the French Second Army on the right bank of the Meuse. Inspired by the experience of the Second Battle of Champagne in 1915, the Germans The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. planned rapidly to capture the Meuse Heights, an excellent defensive position with good observation for the artillery to bombard Verdun. The Germans hoped that the French would commit their strategic reserve to recapture the position and suffer catastrophic losses in a battle of annihilation, not costly for the Germans because of their tactical advantage.

The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. planned rapidly to capture the Meuse Heights, an excellent defensive position with good observation for the artillery to bombard Verdun. The Germans hoped that the French would commit their strategic reserve to recapture the position and suffer catastrophic losses in a battle of annihilation, not costly for the Germans because of their tactical advantage.

Poor weather delayed the beginning of the German attack until 21 February, but the Germans enjoyed initial success, capturing Fort Douaumont in the first three days of the offensive. Afterwards the German advance slowed, despite many French casualties. By 6 March, 20 1⁄2 French divisions were in the RFV and a more extensive defence in depth had been constructed. Pétain ordered that no withdrawals were to be made and that counter-attacks were to be conducted, despite exposing French infantry to fire from the German artillery. By 29 March, French artillery on the west bank had begun a constant bombardment of German positions on the east bank, which caused many German infantry casualties.

In March, the German offensive was extended to the left (west) bank of the Meuse, to gain observation of the ground from which French artillery had been firing over the river onto the Meuse Heights. The Germans were able to advance at first but French reinforcements contained the attacks short of their objectives. In early May, the Germans changed tactics and made local attacks and counter-attacks, which gave the French an opportunity to begin an attack against Fort Douaumont. Part of the fort was occupied, until a German counter-attack recaptured the fort and took numerous prisoners. The Germans changed tactics again, alternating their attacks on both banks of the Meuse and in June captured Fort Vaux. The Germans continued the offensive beyond Vaux, towards the last geographical objectives of the original plan, at Fleury-devant-Douaumont and Fort Souville. The Germans drove a salient into the French defences, captured Fleury and came within 4 km (2.5 mi) of the Verdun citadel.

In July 1916, the German offensive was reduced to provide artillery and infantry reinforcements for the Somme front and during local operations, the village of Fleury changed hands sixteen times from 23 June to 17 August. A German attempt to capture Fort Souville in early July was repulsed by artillery and small arms fire. To supply reinforcements for the Somme front, the German offensive was reduced further and attempts were made to deceive the French into expecting more attacks, to keep French reinforcements away from the Somme. In August and December, French counter-offensives recaptured much of the ground lost on the east bank and recovered Fort Douaumont and Fort Vaux.

The Battle of Verdun lasted for 303 days and became the longest and one of the most costly battles in human history. An estimate in 2000 found a total of 714,231 casualties, 377,231 French and 337,000 German, for an average of 70,000 casualties a month; other recent estimates increase the number of casualties to 976,000 during the battle, with 1,250,000 suffered at Verdun during the war.

Background

Strategic Developments

After the German invasion of France French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. had been halted at the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914, the war of movement ended at the Battle of the Yser and the First Battle of Ypres. The Germans built field fortifications to hold the ground captured in 1914 and the French began siege warfare to break through the German defences and recover the lost territory. In late 1914 and in 1915, offensives on the Western Front had failed to gain much ground and been extremely costly in casualties. According to his memoirs written after the war, the Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, believed that although victory might no longer be achieved by a decisive battle, the French army could still be defeated if it suffered a sufficient number of casualties. Falkenhayn offered five corps from the strategic reserve for an offensive at Verdun at the beginning of February 1916 but only for an attack on the east bank of the Meuse. Falkenhayn considered it unlikely the French would be complacent about Verdun; he thought that they might send all their reserves there and begin a counter-offensive elsewhere or fight to hold Verdun while the British

French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. had been halted at the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914, the war of movement ended at the Battle of the Yser and the First Battle of Ypres. The Germans built field fortifications to hold the ground captured in 1914 and the French began siege warfare to break through the German defences and recover the lost territory. In late 1914 and in 1915, offensives on the Western Front had failed to gain much ground and been extremely costly in casualties. According to his memoirs written after the war, the Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, believed that although victory might no longer be achieved by a decisive battle, the French army could still be defeated if it suffered a sufficient number of casualties. Falkenhayn offered five corps from the strategic reserve for an offensive at Verdun at the beginning of February 1916 but only for an attack on the east bank of the Meuse. Falkenhayn considered it unlikely the French would be complacent about Verdun; he thought that they might send all their reserves there and begin a counter-offensive elsewhere or fight to hold Verdun while the British The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. launched a relief offensive. After the war, the Kaiser and Colonel Tappen, the Operations Officer at Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, General Headquarters), wrote that Falkenhayn believed the last possibility was most likely.

The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. launched a relief offensive. After the war, the Kaiser and Colonel Tappen, the Operations Officer at Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, General Headquarters), wrote that Falkenhayn believed the last possibility was most likely.

By seizing or threatening to capture Verdun, the Germans anticipated that the French would send all their reserves, which would have to attack secure German defensive positions, which were supported by a powerful artillery reserve and be destroyed. In the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive (1 May – 19 September 1915), the German and Austro-Hungarian Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. Austria-Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. Armies attacked Russian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. Austria-Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. Armies attacked Russian Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. defences frontally, after pulverising them with large amounts of heavy artillery. During the Second Battle of Champagne (Herbstschlacht autumn battle) of 25 September – 6 November 1915, the French suffered "extraordinary casualties" from the German heavy artillery, which Falkenhayn considered offered a way out of the dilemma of material inferiority and the growing strength of the Allies. In the north, a British relief offensive would wear down British reserves, to no decisive effect but create the conditions for a German counter-offensive near Arras.

Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. defences frontally, after pulverising them with large amounts of heavy artillery. During the Second Battle of Champagne (Herbstschlacht autumn battle) of 25 September – 6 November 1915, the French suffered "extraordinary casualties" from the German heavy artillery, which Falkenhayn considered offered a way out of the dilemma of material inferiority and the growing strength of the Allies. In the north, a British relief offensive would wear down British reserves, to no decisive effect but create the conditions for a German counter-offensive near Arras.

Hints about Falkenhayn's thinking were picked up by Dutch military intelligence and passed on to the British in December. The German strategy was to create a favourable operational situation without a mass attack, which had been costly and ineffective when it had been tried by the Franco-British, by relying on the power of heavy artillery to inflict mass losses. A limited offensive at Verdun would lead to the destruction of the French strategic reserve in fruitless counter-attacks and the defeat of British reserves in a futile relief offensive, leading to the French accepting a separate peace. If the French refused to negotiate, the second phase of the strategy would begin in which the German armies would attack terminally weakened Franco-British armies, mop up the remains of the French armies and expel the British from Europe. To fulfil this strategy, Falkenhayn needed to hold back enough of the strategic reserve for the Anglo-French relief offensives and then conduct a counter-offensive, which limited the number of divisions which could be sent to the 5th Army at Verdun, for Unternehmen Gericht (Operation Judgement).

The Fortified Region of Verdun (RFV) lay in a salient formed during the German invasion of 1914. The Commander-in-Chief of the French Army, General Joseph Joffre, had concluded from the swift capture of the Belgian Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country as it exists today was established following the 1830 Belgian Revolution. Belgium has also been the battleground of European powers, earning the moniker the "Battlefield of Europe", a reputation reinforced in the 20th century by both world wars. fortresses at the Battle of Liège and at the Siege of Namur in 1914 that fixed defences had been made obsolete by German siege guns. In a directive of the General Staff of 5 August 1915, the RFV was to be stripped of 54 artillery batteries and 128,000 rounds of ammunition. Plans to demolish forts Douaumont and Vaux to deny them to the Germans were made and 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb) of explosives had been laid by the time of the German offensive on 21 February. The 18 large forts and other batteries around Verdun were left with fewer than 300 guns and a small reserve of ammunition while their garrisons had been reduced to small maintenance crews. The railway line from the south into Verdun had been cut during the Battle of Flirey in 1914, with the loss of Saint-Mihiel; the line west from Verdun to Paris was cut at Aubréville in mid-July 1915 by the German 3rd Army, which had attacked southwards through the Argonne Forest for most of the year.

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country as it exists today was established following the 1830 Belgian Revolution. Belgium has also been the battleground of European powers, earning the moniker the "Battlefield of Europe", a reputation reinforced in the 20th century by both world wars. fortresses at the Battle of Liège and at the Siege of Namur in 1914 that fixed defences had been made obsolete by German siege guns. In a directive of the General Staff of 5 August 1915, the RFV was to be stripped of 54 artillery batteries and 128,000 rounds of ammunition. Plans to demolish forts Douaumont and Vaux to deny them to the Germans were made and 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb) of explosives had been laid by the time of the German offensive on 21 February. The 18 large forts and other batteries around Verdun were left with fewer than 300 guns and a small reserve of ammunition while their garrisons had been reduced to small maintenance crews. The railway line from the south into Verdun had been cut during the Battle of Flirey in 1914, with the loss of Saint-Mihiel; the line west from Verdun to Paris was cut at Aubréville in mid-July 1915 by the German 3rd Army, which had attacked southwards through the Argonne Forest for most of the year.

These books are available for download with Apple Books on your Mac or iOS device

Région Fortifiée de Verdun

For centuries, Verdun, on the Meuse river, had played an important role in the defence of the French hinterland. Attila the Hun failed to seize the town in the fifth century and when the empire of Charlemagne was divided under the Treaty of Verdun (843), the town became part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 awarded Verdun to France. At the heart of the city was a citadel built by Vauban in the 17th century. A double ring of 28 forts and smaller works (ouvrages) had been built around Verdun on commanding ground, at least 150 m (490 ft) above the river valley, 2.5–8 km (1.6–5.0 mi) from the citadel. A programme had been devised by Séré de Rivières in the 1870s to build two lines of fortresses from Belfort to Épinal and from Verdun to Toul as defensive screens and to enclose towns intended to be the bases for counter-attacks. Many of the Verdun forts had been modernised and made more resistant to artillery, with a reconstruction programme begun at Douaumont in the 1880s. A sand cushion and thick, steel-reinforced concrete tops up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) thick, buried under 1–4 m (3.3–13.1 ft) of earth, were added. The forts and ouvrages were sited to overlook each other for mutual support and the outer ring had a circumference of 45 km (28 mi). The outer forts had 79 guns in shell-proof turrets and more than 200 light guns and machine-guns to protect the ditches around the forts. Six forts had 155 mm guns in retractable turrets and fourteen had retractable twin 75 mm turrets.

In 1903, Douaumont was equipped with a new concrete bunker (Casemate de Bourges), containing two 75 mm field guns to cover the south-western approach and the defensive works along the ridge to Ouvrage de Froidterre. More guns were added from 1903–1913, in four retractable steel turrets. The guns could rotate for all-round defence and two smaller versions, at the north-eastern and north-western corners of the fort, housed twin Hotchkiss machine-guns. On the east side of the fort, an armoured turret with a 155 mm short-barrelled gun faced north and north-east and another housed twin 75 mm guns at the north end, to cover the intervals between forts. The fort at Douaumont formed part of a complex of the village, fort, six ouvrages, five shelters, six concrete batteries, an underground infantry shelter, two ammunition depots and several concrete infantry trenches. The Verdun forts had a network of concrete infantry shelters, armoured observation posts, batteries, concrete trenches, command posts and underground shelters between the forts. The artillery comprised c. 1,000 guns, with 250 in reserve and the forts and ouvrages were linked by telephone and telegraph, a narrow-gauge railway system and a road network; on mobilisation, the RFV had a garrison of 66,000 men and rations for six months.

Prelude

German Offensive Preparations

Verdun was isolated on three sides and railway communications to the French rear had been cut except for a light railway; German-controlled railways lay only 24 km (15 mi) to the north of the front line. A corps was moved to the 5th Army to provide labour for the preparation of the offensive. Areas were emptied of French civilians and buildings requisitioned, thousands of kilometres of telephone cable were laid, thousands of tons of ammunition and rations were stored under cover with hundreds of guns installed and camouflaged. Ten new rail lines with twenty stations were built and vast underground shelters (Stollen) were dug 4.5–14 m (15–46 ft) deep, each to accommodate up to 1,200 German infantry. The III Corps, VII Reserve Corps and XVIII Corps were transferred to the 5th Army, each corps being reinforced by 2,400 experienced troops and 2,000 trained recruits. V Corps was placed behind the front line, ready to advance if necessary when the assault divisions were moving up and the XV Corps, with two divisions, was in the 5th Army reserve, ready to advance to mop up as soon as the French defence collapsed.

Special arrangements were made to maintain a high rate of artillery-fire during the offensive, 33 1⁄2 munitions trains per day were to deliver ammunition sufficient for 2,000,000 rounds to be fired in the first six days and another 2,000,000 shells in the next twelve. Five repair shops were built close to the front to reduce delays for maintenance; factories in Germany were made ready, rapidly to refurbish artillery needing more extensive repairs. A redeployment plan for the artillery was devised, for field guns and mobile heavy artillery to be moved forward, under the covering fire of mortars and the super-heavy artillery. A total of 1,201 guns were massed on the Verdun front, two thirds of which were heavy and super-heavy artillery, which had been obtained by stripping the modern German artillery from the rest of the Western Front and substituting it with older types and captured Russian guns. The German artillery could fire into the Verdun salient from three directions, yet remain dispersed.

German Plan of Attack

The 5th Army divided the attack front into areas, A occupied by the VII Reserve Corps, B by the XVIII Corps, C by the III Corps and D on the Woëvre plain by the XV Corps. The preliminary artillery bombardment was to begin in the morning of 12 February. At 5:00 p.m., the infantry in areas A to C would advance in open order, supported by grenade and flame-thrower detachments. Wherever possible, the French advanced trenches were to be occupied and the second position reconnoitred, for the artillery fire on the second day. Great emphasis was placed on limiting German infantry casualties, by sending them to follow up destructive bombardments by the artillery, which was to carry the burden of the offensive in a series of large "attacks with limited objectives", to maintain a relentless pressure on the French. The initial objectives were the Meuse Heights, on a line from Froide Terre to Fort Souville and Fort Tavannes, which would provide a secure defensive position from which to repel French counter-attacks. Relentless pressure was a term added by the 5th Army staff and created ambiguity about the purpose of the offensive. Falkenhayn wanted land to be captured, from which artillery could dominate the battlefield and the 5th Army wanted a quick capture of Verdun. The confusion caused by the ambiguity was left to the corps headquarters to sort out.

Control of the artillery was centralised by an Order for the Activities of the Artillery and Mortars, which stipulated that the corps Generals of Foot Artillery were responsible for local target selection, while co-ordination of flanking fire by neighbouring corps and the fire of certain batteries, was determined by the 5th Army headquarters. French fortifications were to be engaged by the heaviest howitzers and enfilade fire. The heavy artillery was to maintain long-range bombardment of French supply routes and assembly areas; counter-battery fire was reserved for specialist batteries firing gas shells. Co-operation between the artillery and infantry was stressed, with accuracy of the artillery being given priority over rate of fire. The opening bombardment was to build up slowly and Trommelfeuer (a rate of fire so rapid that the sound of shell-explosions merged into a rumble) would not begin until the last hour. As the infantry advanced, the artillery would increase the range of the bombardment to destroy the French second position. Artillery observers were to advance with the infantry and communicate with the guns by field telephones, flares and coloured balloons. When the offensive began, the French were to be bombarded continuously, harassing fire being maintained at night.

French Defensive Preparations

In 1915, 237 guns and 647 long tons (657 t) of ammunition in the forts of the RFV had been removed, leaving only the heavy guns in retractable turrets. The conversion of the RFV to a conventional linear defence, with trenches and barbed wire began but proceeded slowly, after resources were sent west from Verdun for the Second Battle of Champagne (25 September – 6 November 1915). In October 1915, building began on trench lines known as the first, second and third positions and in January 1916, an inspection by General Noël de Castelnau, Chief of Staff at French General Headquarters (GQG), reported that the new defences were satisfactory, except for small deficiencies in three areas. The fortress garrisons had been reduced to small maintenance crews and some of the forts had been readied for demolition. The maintenance garrisons were responsible to the central military bureaucracy in Paris and when the XXX Corps commander, General Chrétien, attempted to inspect Fort Douaumont in January 1916, he was refused entry.

Douaumont was the largest fort in the RFV and by February 1916, the only artillery left in the fort were the 75 mm and 155 mm turret guns and light guns covering the ditch. The fort was used as a barracks by 68 technicians under the command of Warrant-Officer Chenot, the Gardien de Batterie. One of the rotating 155 mm (6.1 in) turrets was partially manned and the other was left empty. The Hotchkiss machine-guns were stored in boxes and four 75 mm guns in the casemates had already been removed. The drawbridge had been jammed in the down position by a German shell and had not been repaired. The coffres (wall bunkers) with Hotchkiss revolver-cannons protecting the moats, were unmanned and over 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) of explosive charges had been placed in the fort to demolish it.

In late January 1916, French intelligence had obtained an accurate assessment of German military capacity and intentions at Verdun but Joffre considered that an attack would be a diversion, because of the lack of an obvious strategic objective. By the time of the German offensive, Joffre expected a bigger attack elsewhere but ordered the VII Corps to Verdun on 23 January, to hold the north face of the west bank. XXX Corps held the salient east of the Meuse to the north and north-east and II Corps held the eastern face of the Meuse Heights; Herr had 8 1⁄2 divisions in the front line, with 2 1⁄2 divisions in close reserve. Groupe d'armées du centre (GAC, General De Langle de Cary) had the I and XX corps with two divisions each in reserve, plus most of the 19th Division; Joffre had 25 divisions in the strategic reserve. French artillery reinforcements had brought the total at Verdun to 388 field guns and 244 heavy guns, against 1,201 German guns, two thirds of which were heavy and super heavy, including 14 in (360 mm) and 202 mortars, some being 16 in (410 mm). Eight specialist flame-thrower companies were also sent to the 5th Army.

Castelnau met De Langle de Cary on 25 February, who doubted the east bank could be held. Castelnau disagreed and ordered General Frédéric-Georges Herr the corps commander, to hold the right (east) bank of the Meuse at all costs. Herr sent a division from the west bank and ordered XXX Corps to hold a line from Bras to Douaumont, Vaux and Eix. Pétain took over command of the defence of the RFV at 11:00 p.m., with Colonel Maurice de Barescut as chief of staff and Colonel Bernard Serrigny as head of operations, only to hear that Fort Douaumont had fallen. Pétain ordered for the remaining Verdun forts to be re-garrisoned. Four groups were established, under the command of generals Guillaumat, Balfourier and Duchêne on the right bank and Bazelaire on the left bank. A "line of resistance" was established on the east bank from Souville to Thiaumont, around Fort Douaumont to Fort Vaux, Moulainville and along the ridge of the Woëvre. On the west bank, the line ran from Cumières to Mort Homme, Côte 304 and Avocourt. A "line of panic" was planned in secret as a final line of defence north of Verdun, through forts Belleville, St. Michel and Moulainville. I Corps and XX Corps arrived from 24–26 February, increasing the number of divisions in the RFV to 14 1⁄2. By 6 March, the arrival of the XIII, XXI, XIV and XXXIII corps had increased the total to 20 1⁄2 divisions.

Aftermath

Falkenhayn wrote in his memoir that he sent an appreciation of the strategic situation to the Kaiser in December 1915,

The string in France has reached breaking point. A mass breakthrough—which in any case is beyond our means—is unnecessary. Within our reach there are objectives for the retention of which the French General Staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have. If they do so the forces of France will bleed to death.

- Falkenhayn

The German strategy in 1916 was to inflict mass casualties on the French, a goal achieved against the Russians from 1914 to 1915, to weaken the French Army to the point of collapse. The French Army had to be drawn into circumstances from which it could not escape, for reasons of strategy and prestige. The Germans planned to use a large number of heavy and super-heavy guns to inflict a greater number of casualties than French artillery, which relied mostly upon the 75 mm field gun. In 2007, Foley wrote that Falkenhayn intended an attrition battle from the beginning, contrary to the views of Krumeich, Förster and others but the lack of surviving documents had led to many interpretations of Falkenhayn's strategy. At the time, critics of Falkenhayn claimed that the battle demonstrated that he was indecisive and unfit for command; in 1937, Förster had proposed the view "forcefully". In 1994, Afflerbach questioned the authenticity of this "Christmas Memorandum" in his biography of Falkenhayn; after studying the evidence that had survived in the Kriegsgeschichtliche Forschungsanstalt des Heeres (Army Military History Research Institute) files, he concluded that the memorandum had been written after the war but that it was an accurate reflection of much of Falkenhayn's thinking in 1916.

Krumeich wrote that the Christmas Memorandum had been fabricated to justify a failed strategy and that attrition had been substituted for the capture of Verdun, only after the city was not taken quickly. Foley wrote that after the failure of the Ypres Offensive of 1914, Falkenhayn had returned to the pre-war strategic thinking of Moltke the Elder and Hans Delbrück on Ermattungsstrategie (attrition strategy), because the coalition fighting Germany was too powerful to be decisively defeated by military means. German strategy should aim to divide the Allies, by forcing at least one of the Entente powers into a negotiated peace. An attempt at attrition lay behind the offensive against Russia in 1915 but the Russians had refused to accept German peace feelers, despite the huge defeats inflicted by the Austro-Germans that summer.

With insufficient forces to break through the Western Front and to overcome the Entente reserves behind it, Falkenhayn attempted to force the French to attack instead, by threatening a sensitive point close to the front line. Falkenhayn chose Verdun as the place to force the French to begin a counter-offensive, which would be defeated with huge losses to the French, inflicted by German artillery on the dominating heights around the city. The 5th Army would begin a big offensive with limited objectives, to seize the Meuse Heights on the right bank of the river, from which German artillery could dominate the battlefield. By being forced into a counter-offensive against such formidable positions, the French Army would "bleed itself white". As the French were weakened, the British would be forced to launch a hasty relief offensive, which would be another costly defeat. If such defeats were not enough to force negotiations on the French, a German offensive would mop up the remnants of the Franco-British armies and break the Entente "once and for all".

In a revised instruction to the French army of January 1916, the General Staff (GQG) had stated that equipment could not be fought by men. Firepower could conserve infantry but a battle of material prolonged the war and consumed the troops which had been preserved in earlier battles. In 1915 and early 1916, German industry quintupled the output of heavy artillery and doubled the production of super-heavy artillery. French production had also recovered since 1914 and by February 1916, the army had 3,500 heavy guns. In May 1916, Joffre implemented a plan to issue each division with two groups of 155 mm guns and each corps with four groups of long-range guns. Both sides at Verdun had the means to fire huge numbers of heavy shells to suppress the opposing defences before taking the risk of having infantry move in the open. At the end of May, the Germans had 1,730 heavy guns at Verdun against 548 French, which were sufficient to contain the Germans but not enough for a counter-offensive.

German infantry found that it was easier for the French to endure preparatory bombardments, since French positions tended to be on dominating ground, not always visible and sparsely occupied. As soon as German infantry attacked, the French positions "came to life" and the troops began machine-gun and rapid field artillery fire. On 22 April, the Germans had suffered 1,000 casualties and in mid-April, the French fired 26,000 field artillery shells during an attack to the south-east of Fort Douaumont. A few days after taking over at Verdun, Pétain told the air force commander, Commandant Charles Tricornot de Rose, to sweep away the German air service and to provide observation for the French artillery. German air superiority was challenged and eventually reversed, using eight-aircraft Escadrilles for artillery-observation, counter-battery and tactical support.

The fighting at Verdun was less costly to both sides than the war of movement in 1914, which cost the French c. 850,000 and the Germans c. 670,000 men from August to December. The 5th Army had a lower rate of loss than armies on the Eastern Front in 1915 and the French had a lower average rate of loss at Verdun than the rate over three weeks during the Second Battle of Champagne (September–October 1915), which were not fought as battles of attrition. German loss rates increased relative to French rates from 1:2.2 in early 1915 to close to 1:1 by the end of the battle and rough parity continued during the Nivelle Offensive in 1917. The main cost of attrition tactics was indecision, because limited-objective attacks under an umbrella of massed heavy artillery-fire could succeed but created battles of unlimited duration.

Pétain used a "Noria" (rotation) system, to relieve French troops at Verdun after a short period, which brought most troops of the French army to the Verdun front but for shorter periods than for the German troops. French will to resist did not collapse, the symbolic importance of Verdun proved a rallying point and Falkenhayn was forced to conduct the offensive for much longer and commit far more infantry than intended. By the end of April, most of the German strategic reserve was at Verdun, suffering similar casualties to the French army. The Germans believed that they were inflicting losses at a rate of 5:2; German military intelligence thought that French casualties up to 11 March, had been 100,000 men and Falkenhayn was confident that German artillery could easily inflict another 100,000 losses. In May, Falkenhayn estimated that the French had lost 525,000 men against 250,000 German casualties and that the French strategic reserve had been reduced to 300,000 troops. Actual French losses were c. 130,000 by 1 May and the Noria system had enabled 42 divisions to be withdrawn and rested, when their casualties reached 50 percent. Of the 330 infantry battalions of the French metropolitan army, 259 (78 percent) went to Verdun, against 48 German divisions, 25 percent of the Westheer (western army). Afflerbach wrote that 85 French divisions fought at Verdun and that from February to August, the ratio of German to French losses was 1:1.1, not the third of French losses assumed by Falkenhayn. By 31 August, 5th Army losses were 281,000 and French casualties numbered 315,000 men.

In June 1916, the amount of French artillery at Verdun had been increased to 2,708 guns, including 1,138 seventy-five mm field guns; the French and German armies fired c. 10,000,000 shells, with a weight of 1,350,000 long tons (1,370,000 t) from February–December. The German offensive had been contained by French reinforcements, difficulties of terrain and the weather by May, with the 5th Army infantry stuck in tactically dangerous positions, overlooked by the French on the east bank and the west bank, instead of secure on the Meuse Heights. Attrition of the French forces was inflicted by constant infantry attacks, which were vastly more costly than waiting for French counter-attacks and defeating them with artillery. The stalemate was broken by the Brusilov Offensive and the Anglo-French relief offensive on the Somme, which had been expected to lead to the collapse of the Anglo-French armies. Falkenhayn had begun to remove divisions from the armies on the Western Front in June, to rebuild the strategic reserve but only twelve divisions could be spared. Four divisions were sent to the 2nd Army on the Somme, which had dug a layered defensive system based on the experience of the Herbstschlacht. The situation before the beginning of the battle on the Somme was considered by Falkenhayn to be better than before previous offensives and a relatively easy defeat of the British offensive was anticipated. No divisions were moved from the 6th Army, which had 17 1⁄2 divisions and a large amount of heavy artillery, ready for a counter-offensive when the British offensive had been defeated.

The strength of the Anglo-French offensive surprised Falkenhayn and the staff officers of OHL despite the losses inflicted on the British; the loss of artillery to "overwhelming" counter-battery fire and the policy of instant counter-attack against any Anglo-French advance, led to far more German infantry casualties than at the height of the fighting at Verdun, where 25,989 casualties had been suffered in the first ten days, against 40,187 losses on the Somme. The Brusilov Offensive had recommenced as soon as Russian supplies had been replenished, which inflicted more losses on Austro-Hungarian and German troops during June and July, when the offensive was extended to the north. Falkenhayn was called on to justify his strategy to the Kaiser on 8 July and again advocated sending minimal reinforcements to the east and to continue the "decisive" battle in France, where the Somme offensive was the "last throw of the dice" for the Entente. Falkenhayn had already given up the plan for a counter-offensive near Arras, to reinforce the Russian front and the 2nd Army, with eighteen divisions moved from the reserve and the 6th Army front. By the end of August only one division remained in reserve. The 5th Army had been ordered to limit its attacks at Verdun in June but a final effort was made in July to capture Fort Souville. The effort failed and on 12 July, Falkenhayn ordered a strict defensive policy, permitting only small local attacks, to try to limit the number of troops the French took from the RFV to add to the Somme offensive.

Falkenhayn had underestimated the French, for whom victory at all costs was the only way to justify the sacrifices already made; the pressure imposed on the French army never came close to making the French collapse and triggering a premature British relief offensive. The ability of the German army to inflict disproportionate losses had also been exaggerated, in part because the 5th Army commanders had tried to capture Verdun and attacked regardless of loss; even when reconciled to Falkenhayn's attrition strategy, they continued to use the costly Vernichtungsstrategie (strategy of annihilation) and tactics of Bewegungskrieg (manoeuvre warfare). Failure to reach the Meuse Heights, forced the 5th Army to try to advance from poor tactical positions and to impose attrition by infantry attacks and counter-attacks. The unanticipated duration of the offensive made Verdun a matter of German prestige as much as it was for the French and Falkenhayn became dependent on a British relief offensive and a German counter-offensive to end the stalemate. When it came, the collapse of the southern front in Russia and the power of the Anglo-French attack on the Somme reduced the German armies to holding their positions as best they could. On 29 August, Falkenhayn was sacked and replaced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, who ended the German offensive at Verdun on 2 September.

Casualties

In 1980, Terraine gave c. 750,000 Franco-German casualties in 299 days of battle; Dupuy and Dupuy gave 542,000 French casualties in 1993. Heer and Naumann calculated 377,231 French and 337,000 German casualties, a monthly average of 70,000 casualties in 2000. Mason wrote in 2000 that there had been 378,000 French and 337,000 German casualties. In 2003, Clayton quoted 330,000 German casualties, of whom 143,000 were killed or missing and 351,000 French losses, 56,000 killed, 100,000 missing or prisoners and 195,000 wounded. Writing in 2005, Doughty gave French casualties at Verdun, from 21 February to 20 December 1916 as 377,231 men of 579,798 losses at Verdun and the Somme; 16 percent of Verdun casualties were known to have been killed, 56 percent wounded and 28 percent missing, many of whom were eventually presumed dead. Doughty wrote that other historians had followed Churchill (1927) who gave a figure of 442,000 casualties by mistakenly including all French losses on the Western Front. (In 2014, Philpott recorded 377,000 French casualties, of whom 162,000 men had been killed, German casualties were 337,000 men and a recent estimate of casualties at Verdun from 1914 to 1918 was 1,250,000 men).

In the second edition of The World Crisis (1938), Churchill wrote that the figure of 442,000 was for other ranks and the figure of "probably" 460,000 casualties included officers. Churchill gave a figure of 278,000 German casualties of whom 72,000 were killed and expressed dismay that French casualties had exceeded German by about 3:2. Churchill also stated that an eighth needed to be deducted from his figures for both sides to account for casualties on other sectors, giving 403,000 French and 244,000 German casualties. Grant gave a figure of 434,000 German casualties in 2005. In 2005, Foley used calculations made by Wendt in 1931 to give German casualties at Verdun from 21 February to 31 August 1916 as 281,000, against 315,000 French casualties. Afflerbach used the same source in 2000 to give 336,000 German and 365,000 French casualties at Verdun, from February to December 1916.

In 2013, Jankowski wrote that since the beginning of the war, French army units had produced états numériques des pertes every five days for the Bureau of Personnel at GQG. The health service at the Ministry of War received daily counts of wounded taken in by hospitals and other services but casualty data was dispersed among regimental depots, GQG, the État Civil, which recorded deaths, the Service de Santé, which counted injuries and illnesses and the Renseignements aux Familles, which communicated with next of kin. Regimental depots were ordered to keep fiches de position to record losses continuously and the Première Bureau of GQG began to compare the five-day field reports with the records of hospital admissions. The new system was used to calculate losses since August 1914, which took several months but the system had become established by February 1916. The états numériques des pertes were used to calculate casualty figures published in the Journal Officiel, the French Official History and other publications.

The German armies compiled Verlustlisten every ten days, which were published by the Reichsarchiv in the deutsches Jahrbuch of 1924–1925. German medical units kept detailed records of medical treatment at the front and in hospital and in 1923 the Zentral Nachweiseamt published an amended edition of the lists produced during the war, incorporating medical service data not in the Verlustlisten. Monthly figures of wounded and ill servicemen that were treated were published in 1934 in the Sanitätsbericht. Using such sources for comparisons of losses during a battle is difficult, because the information recorded losses over time, rather than place. Losses calculated for particular battles could be inconsistent, as in the Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914–1920 (1922). In the early 1920s, Louis Marin reported to the Chamber of Deputies but could not give figures per battle, except for some by using numerical reports from the armies, which were unreliable unless reconciled with the system established in 1916.

Some French data excluded those lightly wounded but some did not. In April 1917, GQG required that the états numériques des pertes discriminate between the lightly wounded, treated at the front over a period of 20–30 days and severely wounded evacuated to hospitals. Uncertainty over the criteria had not been resolved before the war ended, Verlustlisten excluded lightly wounded and the Zentral Nachweiseamt records included them. Churchill revised German statistics, by adding 2 percent for unrecorded wounded in The World Crisis, written in the 1920s and the British official historian added 30 percent. For the Battle of Verdun, the Sanitätsbericht contained incomplete data for the Verdun area, did not define "wounded" and the 5th Army field reports exclude them. The Marin Report and Service de Santé covered different periods but included lightly wounded. Churchill used a Reichsarchiv figure of 428,000 casualties and took a figure of 532,500 casualties from the Marin Report, for March to June and November to December 1916, for all the Western Front.

The états numériques des pertes give French losses in a range from 348,000 to 378,000 and in 1930, Wendt recorded French Second Army and German 5th Army casualties of 362,000 and 336,831 respectively, from 21 February to 20 December, not taking account of the inclusion or exclusion of lightly wounded. In 2006, McRandle and Quirk used the Sanitätsbericht to adjust the Verlustlisten by an increase of c. 11 percent, which gave a total of 373,882 German casualties, compared to the French Official History record by 20 December 1916, of 373,231 French losses. A German record from the Sanitätsbericht, which explicitly excluded lightly wounded, compared German losses at Verdun in 1916, which averaged 37.7 casualties for each 1,000 men, with the 9th Army in Poland 1914 average of 48.1 per 1,000, the 11th Army average in Galicia 1915 of 52.4 per 1,000 men, the 1st Army Somme 1916 average of 54.7 per 1,000 and the 2nd Army average on the Somme of 39.1 per 1,000 men. Jankowski estimated an equivalent figure for the French Second Army of 40.9 men per 1,000, including lightly wounded. With a c. 11 percent adjustment to the German figure of 37.7 per 1,000 to include lightly wounded, following the views of McRandle and Quirk, the loss rate is analogous to the estimate for French casualties.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles "World War", "World War I", and "Battle of Verdun", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.