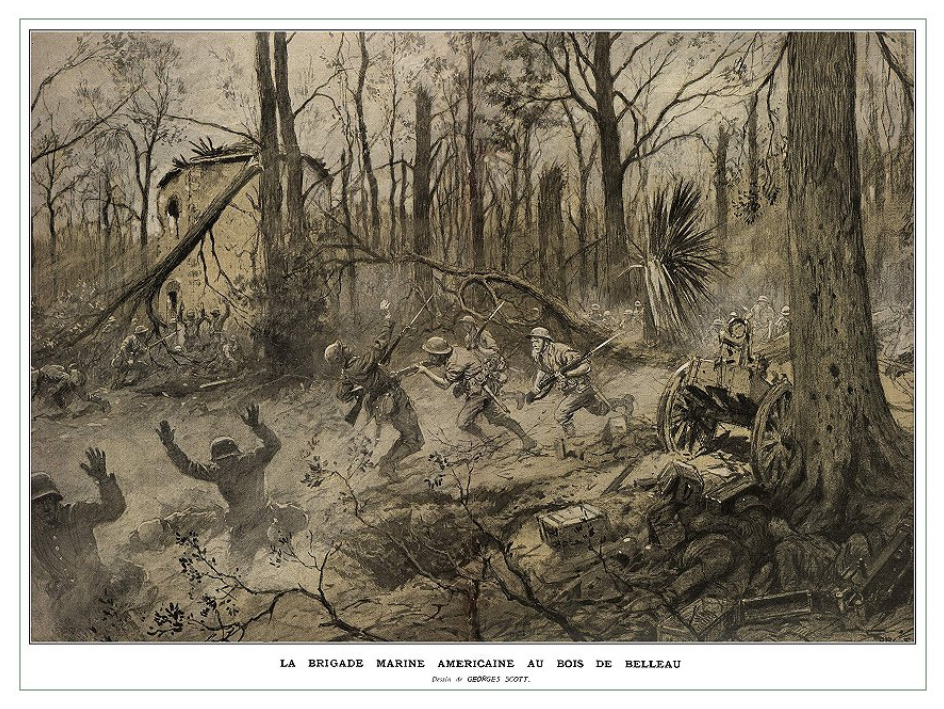

World War I (1914-1918)

Battle of Albert

The Battle of Albert (1–13 July 1916), comprised the first two weeks of Anglo-French offensive operations in the Battle of the Somme. The Allied preparatory artillery bombardment commenced on 24 June and the Anglo-French infantry attacked on 1 July, on the south bank from Foucaucourt to the Somme and from the Somme north to Gommecourt, 2 mi (3.2 km) beyond Serre.

The French French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. Sixth army and the right wing of the British

French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. Sixth army and the right wing of the British The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. Fourth Army inflicted a considerable defeat on the German 2nd Army but from the Albert–Bapaume road to Gommecourt the British attack was a disaster, where most of the c. 60,000 British casualties of the day were incurred. Against the wishes of General Joseph Joffre, General Sir Douglas Haig abandoned the offensive north of the road, to reinforce the success in the south, where the Anglo-French forces pressed forward through several intermediate lines, until close to the German

The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. Fourth Army inflicted a considerable defeat on the German 2nd Army but from the Albert–Bapaume road to Gommecourt the British attack was a disaster, where most of the c. 60,000 British casualties of the day were incurred. Against the wishes of General Joseph Joffre, General Sir Douglas Haig abandoned the offensive north of the road, to reinforce the success in the south, where the Anglo-French forces pressed forward through several intermediate lines, until close to the German The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. second position.

The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. second position.

The French Sixth Army advanced across the Flaucourt plateau on the south bank and reached Flaucourt village by the evening of 3 July, taking Belloy-en-Santerre and Feullières on 4 July and piercing the German third line opposite Péronne at La Maisonette and Biaches by the evening of 10 July. German reinforcements were then able to slow the French advance and defeat attacks on Barleux. On the north bank, XX Corps was ordered to consolidate the ground captured on 1 July, except for the completion of the advance to the first objective at Hem next to the river, which was captured on 5 July. Some minor attacks took place and German counter-attacks at Hem on 6–7 July nearly retook the village. A German attack at Bois Favières delayed a joint Anglo-French attack from Hardecourt to Trônes Wood by 24 hours until 8 July.

British attacks south of the road between Albert and Bapaume began on 2 July, despite congested supply routes to the French XX Corps, British XIII Corps, XV Corps and III Corps. La Boisselle near the road was captured on 4 July, Bernafay and Caterpillar woods were occupied from 3–4 July and then fighting to capture Trônes Wood, Mametz Wood and Contalmaison took place until early on 14 July, when the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July) began. German reinforcements reaching the Somme front were thrown into the defensive battle as soon as they arrived and had many casualties, as did the British attackers. Both sides were reduced to piecemeal operations, which were hurried, poorly organised, sent troops unfamiliar with the ground into action with inadequate reconnaissance. Attacks were poorly supported by artillery-fire, which was not adequately co-ordinated with the infantry and sometimes fired on ground occupied by friendly troops. Much criticism has been made of the British attacks as uncoordinated, tactically crude and wasteful of manpower, which gave the Germans an opportunity to concentrate their inferior resources on narrow fronts.

The loss of about 60,000 British casualties in one day was never repeated but from 2 to 13 July, the British had about 25,000 more casualties; rate of loss changed from about 60,000 to 2,083 per day. From 1 to 10 July, the Germans had 40,187 casualties against a British total of about 85,000 men from 1 to 13 July. The effect of the battle on the defenders has received less attention in English-language writing. The strain imposed by the British attacks after 1 July and the French advance on the south bank led General Fritz von Below to issue an order of the day on 3 July, forbidding voluntary withdrawals ("The enemy should have to carve his way over heaps of corpses.") after Falkenhayn had sacked General Paul Grünert, the 2nd Army chief of staff and Günther von Pannewitz, the commander of XVII Corps, for ordering the corps to withdraw to the third position close to Péronne. The German offensive at Verdun had already been reduced on 24 June, to conserve manpower and ammunition; after the failure to capture Fort Souville at Verdun on 12 July, Falkenhayn ordered a "strict defensive" and the transfer of more troops and artillery to the Somme front, which was the first strategic effect of the Anglo-French offensive.

Strategic Developments

The Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn intended to split the British and French alliance in 1916 and end the war, before the Central Powers were crushed by Allied material superiority. To obtain decisive victory, Falkenhayn needed to find a way to break through the Western Front and defeat the strategic reserves, which the Allies could move into the path of a breakthrough. Falkenhayn planned to provoke the French into attacking, by threatening a sensitive point close to the existing front line. Falkenhayn chose to attack towards Verdun over the Meuse Heights, to capture ground which overlooked Verdun and make it untenable. The French would have to conduct a counter-offensive, on ground dominated by the German army and ringed with masses of heavy artillery, inevitably leading to huge losses and bringing the French army close to collapse. The British would have no choice but to begin a hasty relief-offensive, to divert German attention from Verdun but would also suffer huge losses. If these defeats were not enough, Germany would attack both armies and end the western alliance for good.

The unexpected length and cost of the Verdun offensive and the underestimation of the need to replace exhausted units there, depleted the German strategic reserve placed behind the 6th Army, which held the front between Hannescamps 11 mi (18 km) south-west of Arras and St Eloi, south of Ypres and reduced the German counter-offensive strategy north of the Somme to one of passive and unyielding defence. On the Eastern Front the Brusilov Offensive began on 4 June and on 7 June a German corps was sent to Russia Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. from the western reserve, followed quickly by two more divisions. After the failure to capture Fort Souville at Verdun on 12 July, Falkenhayn was obliged to suspend the offensive and reinforce the defences of the Somme front, even though the 5th Army was on the brink of the strategic objectives of the offensive.

Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. from the western reserve, followed quickly by two more divisions. After the failure to capture Fort Souville at Verdun on 12 July, Falkenhayn was obliged to suspend the offensive and reinforce the defences of the Somme front, even though the 5th Army was on the brink of the strategic objectives of the offensive.

The Anglo-French plan for an offensive on the Somme front had been decided at the Chantilly Conference of December 1915 as part of a general Allied offensive by the British, French, Italians The Kingdom of Italy was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946. The state resulted from a decades-long process, the Risorgimento, of consolidating the different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state. That process was influenced by the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered Italy's legal predecessor state. and Russians. Anglo-French intentions were quickly undermined by the German offensive at Verdun which began on 21 February 1916. The original proposal was for the British to conduct preparatory offensives in 1916 before a great Anglo-French offensive from Lassigny to Gommecourt, in which the British would participate with all the forces they still had available. The French would attack with 39 divisions on a front of 30 mi (48 km) and the British with c. 25 divisions on 15 mi (24 km) on the northern French flank. The course of the battle at Verdun led the French gradually to reduce the number of divisions for operations on the Somme, until it became a supporting attack for the British on a 6 mi (9.7 km) front with only five divisions. The original intention had been for a rapid eastwards advance to the higher ground beyond the Somme and Tortille rivers, during which the British would occupy the ground beyond the upper Ancre. The combined armies would then attack south-east and north-east, to roll up the German defences on the flanks of the breakthrough. By 1 July, the strategic ambition of the Somme offensive had been reduced in scope from a decisive blow against Germany, to relieving the pressure on the French army at Verdun and contributing with the Russian and Italian armies, to the common Allied offensive.

The Kingdom of Italy was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946. The state resulted from a decades-long process, the Risorgimento, of consolidating the different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state. That process was influenced by the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered Italy's legal predecessor state. and Russians. Anglo-French intentions were quickly undermined by the German offensive at Verdun which began on 21 February 1916. The original proposal was for the British to conduct preparatory offensives in 1916 before a great Anglo-French offensive from Lassigny to Gommecourt, in which the British would participate with all the forces they still had available. The French would attack with 39 divisions on a front of 30 mi (48 km) and the British with c. 25 divisions on 15 mi (24 km) on the northern French flank. The course of the battle at Verdun led the French gradually to reduce the number of divisions for operations on the Somme, until it became a supporting attack for the British on a 6 mi (9.7 km) front with only five divisions. The original intention had been for a rapid eastwards advance to the higher ground beyond the Somme and Tortille rivers, during which the British would occupy the ground beyond the upper Ancre. The combined armies would then attack south-east and north-east, to roll up the German defences on the flanks of the breakthrough. By 1 July, the strategic ambition of the Somme offensive had been reduced in scope from a decisive blow against Germany, to relieving the pressure on the French army at Verdun and contributing with the Russian and Italian armies, to the common Allied offensive.

Tactical Developments

1 July

The First day on the Somme was the opening day of the Battle of Albert (1–13 July 1916). Nine corps of the French Sixth Army, the British Fourth and Third armies, attacked the German 2nd Army of General von Below, from Foucaucourt on the south bank to Serre, north of the Ancre and at Gommecourt 2 mi (3.2 km) beyond. The objective of the attack was to capture the German first and second positions from Serre south to the Albert–Bapaume road and the first position from the road south to Foucaucourt. The German defence south of the road mostly collapsed and the French had "complete success" on both banks of the Somme, as did the British from Maricourt on the army boundary, where XIII Corps took Montauban and reached all its objectives and XV Corps captured Mametz and isolated Fricourt. The III Corps attack either side of the Albert–Bapaume road was a disaster, making a substantial advance next to the 21st Division on the right and only a short advance at Lochnagar Crater and to the south of La Boisselle, with the largest number of casualties of the day being incurred by the 34th Division. Further north, X Corps captured part of the Leipzig Redoubt, failed opposite Thiepval and had a great but temporary success on the left, where the 36th Division overran the German front line and captured Schwaben and Stuff redoubts.

German counter-attacks during the afternoon, recaptured most of the lost ground and fresh attacks against Thiepval were defeated, with more great loss to the British. On the north bank of the Ancre, the attack of VIII Corps was another disaster, with large numbers of British troops being shot down in no man's land. The VII Corps diversion at Gommecourt was also costly, with only a partial and temporary advance south of the village. The German defeats from Foucaucourt to the Albert–Bapaume road, left the German defence south of the Somme incapable of resisting another attack and a substantial German retreat began, from the Flaucourt plateau towards Péronne, while north of the river, Fricourt was abandoned. The British army had suffered its highest number of casualties in a day and the elaborate defences built by the Germans, had collapsed from Foucaucourt south of the Somme, to the area just south of the Albert–Bapaume road on the north side of the river, throwing the defence into a crisis and leaving the Poilus "buoyant". A German counter-attack north of the Somme was ordered but took until 3:00 a.m. on 2 July to begin.

2–13 July

It took until 4 July for the British relieve the divisions shattered by the attack of 1 July and resume operations south of the Albert–Bapaume road. The number of German defenders in the area was underestimated but British Intelligence reports of a state of chaos in the German 2nd Army and piecemeal reinforcement of threatened areas, were accurate. The British changed tactics after 1 July and used the French method of smaller, shallower and artillery-laden attacks. Operations were conducted to advance south of the Albert–Bapaume road, towards the German second position, in time for a second general attack on 10 July, which due to the effect of the German defence and Anglo-French supply difficulties in the Maricourt Salient, was postponed to 14 July. German counter-attacks were as costly as British-French attacks and the loss of the most elaborately fortified German positions, like those at La Boisselle, prompted determined German efforts to recapture them. A combined Anglo-French attack was planned for 7 July, then postponed until 8 July, after a German counter-attack at Bois Favière captured part of the wood. The inherent difficulties of coalition warfare, were made worse by the German defensive effort and several downpours of rain, which turned the ground to mud and filled shell-holes with water, making movement difficult, even in areas not under fire.

In the afternoon of 1 July, Falkenhayn arrived at the 2nd Army headquarters and found that part of the second line, south of the Somme, had been abandoned for a new shorter line. Falkenhayn sacked the Chief of Staff Major-General Paul Grünert and appointed Colonel von Loßberg, who extracted a promise from Falkenhayn to stop operations at Verdun and arrived on the Somme front at 5:00 a.m. on 2 July. Loßberg studied the battlefield from a hill north of Péronne then toured units, reiterating the ruling that no ground be abandoned regardless of the tactical situation. Loßberg and General Fritz von Below agreed that the defence should be conducted by a thin forward line, supported by immediate counter-attacks (Gegenstösse) which if unsuccessful, were to be followed by deliberate counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe). A new telephone system was to be installed parallel to the battlefront, out of artillery range with branches running forward to headquarters. A beginning was made on revising the artillery command organisation, by uniting divisional and heavy artillery headquarters in each divisional sector. Artillery-observation posts were withdrawn from the front line and placed several hundred yards/metres behind, where visibility was not as restricted by smoke and dust thrown about by shell-explosions. The flow of reinforcements was too slow to establish a line of reserve divisions behind the battlefront, a practice which had been a great success in the Herbstschlacht (Second Battle of Champagne September–October 1915). German reserves were sent into action in companies and battalions, as soon as they arrived, which disorganised formed units and reduced their effectiveness; many of the best trained and experienced men in the German divisions on the Somme, were lost and could not be replaced.

Aftermath

Prior and Wilson contradicted a version of the "traditional" narrative of the First Day of the Somme, which had been established in the writings of John Buchan, Basil Liddell Hart, Charles Cruttwell, Martin Middlebrook, Correlli Barnett and many others. Of 80 British battalions which attacked on 1 July, 53 crept into no man's land, ten rushed the German front line from the British front trench and only twelve advanced at a steady pace. The slow advances of some of the twelve battalions took place behind a creeping barrage and were the most successful attacks of the day. Prior and Wilson wrote that the deciding factor in the success of British infantry battalions was the destructive effect of British artillery; if German gunners and machine-gun crews survived the bombardment, no infantry tactic could overcome their fire power. Ernst von Hoeppner wrote that German air units were overwhelmed by the number and aggression of British and French air crews, who gained air supremacy and reduced the Fliegertruppen "to a state of impotence". Hoeppner wrote that Anglo-French artillery-observation aircraft were their most effective weapon, operating in "perfect accord" with their artillery and "annihilating" the German guns, although the French aviators were superior to the British. Low-altitude flying for machine-gun attacks on German infantry had little practical effect but the depression of German infantry morale was much greater, leading to a belief that return fire had no effect on Allied aircraft and that all aeroplanes seen were British or French, which led to more demands from the infantry for air protection by the Fliegertruppen, despite their unsuitable aircraft.

By 3 July, Joffre, Haig and Rawlinson accepted that the offensive north of the Albert–Bapaume road could not quickly be resumed. Gough had reported that the positions of X Corps and VIII Corps were full of dead and wounded and that several of the divisions shattered on 1 July had not been relieved. Before the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July), the Fourth Army made 46 attacks using 86 battalions, which lost another c. 25,000 casualties. On average 14 percent of the Fourth Army attacked each day and in the largest attack on 7 July, only 19 of 72 battalions (26 percent) were engaged. Artillery support was criticised, since corps artillery rarely co-operated with that of neighbouring corps. Prior and Wilson called the British attacks a succession of narrow-front operations without adequate artillery preparation, which allowed the Germans to concentrate more men and fire power against the attacks, when broader-front attacks would have made the Germans disperse their resources. The British were still able to capture Trônes Wood, Mametz Wood, Contalmaison and La Boisselle in twelve days and added 20 sq mi (52 km2) to the 3 sq mi (7.8 km2) captured on 1 July. The German defence south of the Albert–Bapaume road had been disorganised by the British exploitation of the success of 1 July. Much of the German artillery in the area had been destroyed and the German resort to unyielding defence and instant counter-attacks led them to throw in reserves "helter-skelter", rather than hold them back for better-prepared attacks. Prior and Wilson wrote that the Germans should have slowly withdrawn to straighten the line and conserve manpower, rather than sacking staff officers for the withdrawal of 2 July and issuing a no-retreat order.

Philpott wrote that in the English-speaking world, 1 July had become a metaphor of "futility and slaughter", with 56,886 British casualties contrasted with 1,590 French losses. The huge losses of the French armies in 1915 and the refinement of French offensive tactics that took place before the opening of the battle are overlooked, as is the disarray of the Germans after their defences were smashed and the garrisons killed or captured. The Anglo-French had gained a local advantage by the afternoon of 1 July, having breached the German defences either side of the Somme. The 13 mi (21 km) gap left the German second line between Assevillers and Fricourt vulnerable to a new attack but the "break-in" was not at the anticipated place and so exploitation was reduced to improvised attacks. German reserves on the Somme had been committed and reinforcements sent forward but unexpected delays had occurred, particularly to the 5th Division, which was caught in the railway bombing at St Quentin. Signs of panic were seen on the south bank and a rapid withdrawal was made to the third position at Biaches and La Maisonette. The French XX Corps on the north bank was held back as the troops on either side pressed forward, the British managing a small advance at La Boisselle.

Philpott wrote that the meeting between Joffre, Haig and Foch on 3 July was far less cordial than in other accounts but that over the next day a compromise was agreed, that the British would transfer their main effort south of the Albert–Bapaume road. Foch was instructed by Joffre to co-ordinate the Anglo-French effort on the Somme. The German policy of unyielding defence and counter-attack slowed the British advance but exposed German troops to British artillery directed by air observation, which increased in effectiveness during the period. British attacks have been criticised as amateurish, poorly co-ordinated, in insufficient strength and with inadequate artillery support but most German counter-attacks were also poorly organised and defeated in detail. After the first few days, battalions had been withdrawn from German divisions to the south and sent to the Somme and on the south bank the XVII Corps (Gruppe von Quast) had battalions from eleven divisions under command. Despite their difficulties, the British captured elaborately fortified and tenaciously defended German positions relatively quickly by local initiatives from regimental officers; by 13 July the Anglo-French had captured 19,500 prisoners and 94 guns. The crisis in the French defence of Verdun had been overcome, with a relaxation of German pressure on 24 June and a "strict defensive" imposed by Falkenhayn on 12 July after the failure at Fort Souville. The battles at Verdun and the Somme had a reciprocal effects and for the rest of 1916, both sides tried to keep their opponents pinned down at Verdun to obstruct their efforts on the Somme.

Harris wrote that the difference between the Franco-British success in the south and British failure in the north on 1 July, particularly given the number of British casualties on the first day, had been explained by reference to greater French experience, better artillery and superior infantry tactics. On the first day, the French artillery had been so effective, that infantry tactics were irrelevant in places; on the south bank, the French attack took the defenders by surprise. Harris noted that the British had also succeeded in the south and the victory was in the area expected to be least successful. Harris wrote that it was common to ignore the influence of the opponent and that the Germans were weakest in the south, with fewer men, guns and fortifications, based on terrain less easy to defend and had made their principal defensive effort north of the Somme, where the Anglo-French had also made their main effort. Low ground on the south bank left the Germans at a tactical disadvantage against Anglo-French air power, which kept the skies clear of German aircraft, as artillery-observation and contact-patrol aircraft spotted for French artillery and kept headquarters relatively well informed. Harris wrote that the objective in the south was the German first position, which had been exceptionally damaged by the Allied artillery.

Harris blamed Haig for the decision to attempt to take the second German position, north of the Albert–Bapaume road on the first day, although he was unconvinced that the extra depth of the final objective led to the British artillery unduly to dilute the density of bombardment of the first position. Harris also criticised the breadth of the attack and laid blame on Rawlinson and his chief of staff as well; Harris called this the main reason for the dissipation of British artillery over too great an area. The French had attacked cautiously, behind a wall of heavy artillery-fire and achieved their objectives with minimal casualties; Harris wrote that Haig could easily have adopted a similar approach. By 2 July, seven German divisions were en route to the Somme front and another seven by 9 July; Falkenhayn had suspended the Verdun offensive on 12 July and abandoned his plan to use the Sixth Army for a counter-offensive at Arras, once the British attacks on the Somme had been destroyed. Haig urged that the British attacks on Trônes Wood, Mametz Wood and Contalmaison be hurried but the Fourth Army headquarters delegated responsibility to the corps, which attacked piecemeal, using little of the Fourth Army artillery strength.

Narrow-front attacks invited counter-attack but German efforts proved as ineffective and costly as many British attacks. The British lost another c. 25,000 casualties but Harris wrote that hurried, poorly co-ordinated attacks were not necessarily wrong. Delay would have benefitted the German defenders more than the attackers and the main fault of the British was to take until 4 July to attack again, which failed to exploit all of the German disorganisation caused by the attack of 1 July. The Franco-British had gained the initiative by mid-July, although joint operations on the Somme proved extremely difficult to organise. British attacks south of the Albert–Bapaume road from 2–13 July, denied the Germans time to reorganise and forced them into piecemeal reactions, the German infantry finding themselves in a "meat grinder". Reaching positions suitable for an attack on Bazentin Ridge, was a substantial success for the Fourth Army.

Duffy wrote that the British losses on 1 July 1916, were greater than those of the Crimean, Boer and Korean wars combined and that the "unique volunteer culture" of the Pals battalions had been killed with the men. Not all of the events of 1 July were British defeats, since the German plan for a counter-offensive in the Sixth Army was abandoned and the Verdun offensive was suspended on 12 July. German newspapers reported that the Somme battle was part of a concerted offensive and that unity of action by Germany's enemies had been achieved. British prisoners taken north of the Albert–Bapaume road said that the attacks had failed, because the arrival of reinforcements had been unpredictable, German barbed wire had been astonishingly resilient and the resistance of German troops in the front and second lines was a surprise. German machine-gunners held their fire until British troops were within 30–50 yd (27–46 m), causing surprise, disorganisation and mass casualties; British officers were excoriated for inexperience and incompetence. The variation of British infantry tactics and formations was not noticed by German witnesses, who described massed formations, unlike those of the French and German armies.

All of the prisoners stated that machine-guns caused the most casualties and that where they had reached the German positions, they had been cut off by artillery barrages in no man's land and German infantry emerging from underground shelters behind them. Duffy wrote that the German high command had been shaken by the opening of the Somme offensive and the sackings ordered by Falkenhayn. A sense of crisis persisted, with rumours of breakthroughs being taken seriously. The power and persistence of the Anglo-French attacks surprised the German commanders and by 9 July, fourteen reinforcing divisions had been committed to the battle. Rumours, that conditions in the battle were worse than in 1915 circulated amongst the German soldiery, who were sent into action piecemeal rather than in their normal units. The German system of devolved command left battalions isolated, when they were split up to resist attacks being made in "overwhelming force". British historians called 2–13 July a period of failure, in which 46 attacks cost c. 25,000 men but to the Germans, the period from 1–14 July was one where they lost the initiative and were constantly kept off balance.

Sheldon called the officers sacked by Falkenhayn scapegoats; the survivors of the attacks of 1 July had to hang on until reserves arrived, who lost many casualties when sent to the most threatened areas. On the French front, a German regimental commander explained that the loss of Curlu, was caused by the regiment not being sent forward until the destructive bombardment had begun, that there was not enough material to build defences and that the accommodation of the troops was changed frequently. Night work became essential and a lack of rest reduced the efficiency of the troops, separation of the battalions of the regiment in the week before 1 July disrupted internal administration and the machine-gun detachments and infantry companies were attached to other units, which made it impossible to command the regiment as a tactical unit.

Sheldon judged the German loss of the initiative to have begun before 1 July, when the preliminary bombardment prevented the defenders from moving or being supplied. On the south bank, the first day was a disaster, with over-extended infantry units suffering many casualties and many machine-guns and mortars being destroyed by the French artillery. The French had ten heavy batteries per 0.62 mi (1 km) of front, the advantage of aircraft observation and eighteen observation balloons opposite one German division, which suppressed the German artillery by 11:00 a.m. Sheldon wrote that the change of emphasis by the British to limited local attacks was the only way to keep pressure on the German defence and honour the commitment made at Chantilly. This loyalty meant that the British had to make a slow advance, over ground which offered considerable scope for the German defenders.

Casualties

French casualties on 1 July were 1,590 British casualties on 1 July were 57,470 and c. 25,000 more were lost from 2–13 July. German casualties on 1 July were c. 12,000 men and from 1–10 July increased to 40,187 men. Fayolle recorded that 19,500 prisoners had been taken by the Anglo-French armies. The 7th Division lost 3,824 casualties from 1–5 July. The 12th Division lost 4,721 casualties from 1–8 July. By the time of its relief on 11 July the 17th Division had lost 4,771 casualties. The 18th Division was relieved by the 3rd Division on 8 July, having lost 3,400 casualties since 1 July. By noon on 11 July the 23rd Division was relieved by the 1st Division, having lost 3,485 men up to 10 July. The 30th Division lost another 2,300 men in five days, after only a short period out of the line. The 34th Division had the most casualties of any British division involved in the battle, losing 6,811 men from 1–5 July, which left the 102nd and 103rd Brigades "shattered". From 5–12 July the 38th Division had c. 4,000 casualties. In 2013, Whitehead recorded that in the casualty reporting period from 1–10 July, the 2nd Army had 5,786 men killed, 22,095 men wounded, 18,434 men missing and 7,539 men sick.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles "World War", "World War I", and "Battle of Albert", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.