World War I (1914-1918)

Battle of Bazentin Ridge

The Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July 1916) was part of the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November) on the Western Front in France, during the First World War.

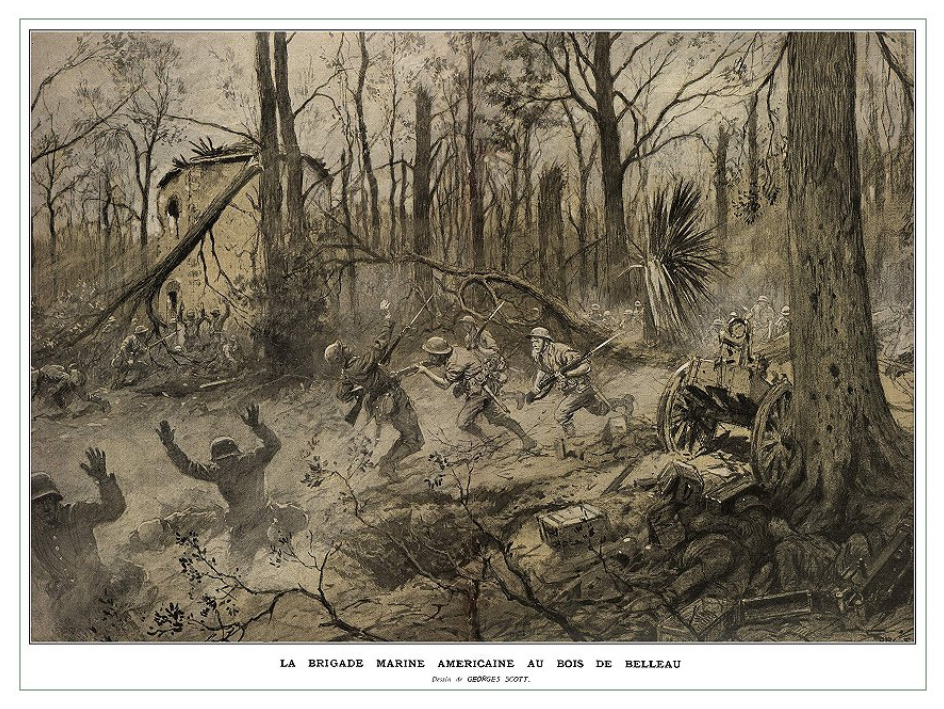

The British Fourth Army (General Henry Rawlinson) made a dawn attack on 14 July, against the German 2nd Army (General Fritz von Below) in the Braune Stellung from Delville Wood westwards to Bazentin le Petit Wood. Dismissed beforehand by a French French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. commander as "an attack organized for amateurs by amateurs", the attack succeeded. Attempts to use the opportunity to capture High Wood failed due to the German

French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. commander as "an attack organized for amateurs by amateurs", the attack succeeded. Attempts to use the opportunity to capture High Wood failed due to the German The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. success in holding on to the north end of Logueval and parts of Delville Wood, from which attacks on High Wood could be engaged from the flank. Cavalry, intended to provide a faster-moving force of exploitation, were badly delayed by the devastated ground, shell-holes and derelict trenches.

The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. success in holding on to the north end of Logueval and parts of Delville Wood, from which attacks on High Wood could be engaged from the flank. Cavalry, intended to provide a faster-moving force of exploitation, were badly delayed by the devastated ground, shell-holes and derelict trenches.

In the afternoon, infantry of the 7th Division attacked High Wood, when an earlier attack could have entered the wood unopposed. The British The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. found that German troops had occupied parts of the wood and also held the Switch Line along the ridge, that cut through the north-east part of the wood. The cavalry eventually attacked east of the wood and overran German infantry hiding in standing crops, inflicting about 100 casualties for a loss of eight troopers. The attack was assisted by an artillery-observation aircraft, whose crew saw the Germans in the crops and fired at them with Lewis guns. The British struggled to exploit the success and the 2nd Army recovered, leading to another period of attritional line straightening attacks and German counter-attacks, before the British and French general attacks of September.

The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. found that German troops had occupied parts of the wood and also held the Switch Line along the ridge, that cut through the north-east part of the wood. The cavalry eventually attacked east of the wood and overran German infantry hiding in standing crops, inflicting about 100 casualties for a loss of eight troopers. The attack was assisted by an artillery-observation aircraft, whose crew saw the Germans in the crops and fired at them with Lewis guns. The British struggled to exploit the success and the 2nd Army recovered, leading to another period of attritional line straightening attacks and German counter-attacks, before the British and French general attacks of September.

Strategic Developments

By mid-June, the certainty of an Anglo-French attack on the Somme against the 2nd Army (General der Infanterie Fritz von Below), had led General Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the Großer Generalstab (German General Staff), to send four divisions and artillery reinforcements from the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, Supreme Army Command) reserve, enough to contain the British offensive. The 2nd Army had plenty of time to construct a defence in depth and was better prepared than any previous army to receive an Entente attack. On 15 June, Falkenhayn had informed the 6th Army (Generaloberst Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria) that the main Entente attack would be against the 2nd Army, with a limited attack near Lens on the 6th Army, which held a shorter line than the 2nd Army, with 17 1⁄2 divisions, plentiful heavy artillery and with three divisions of the OHL reserve close by.

The maintenance of the strength of the 6th Army at the expense of the 2nd Army on the Somme was to conserve the means for a counter-offensive north of the Somme front, once the British offensive had been shattered by the 2nd Army. A German attack on Fleury at Verdun from 22–23 June succeeded and then on 24 June, the Verdun offensive was reduced to conserve manpower and ammunition for the coming Entente offensive, except for preparations to attack on Fort Souville in July, to gain control of the heights overlooking Verdun. The fort was the last significant French position on the east bank of the Meuse, the final objective of the offensive that had begun in February 1916, which had been intended to take only a few weeks.

The power of the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme surprised the Germans, despite the costly failure of the British attack on 1 July, north of the Albert–Bapaume road. The extent of Entente artillery fire caused many casualties and much of the 2nd Army artillery, vital to the defensive system, had been lost. The policy of meeting any Anglo-French success with an immediate counter-attack was also costly and in the first ten days, the Germans suffered 40,187 casualties, against 25,989 losses in the first ten days of the Verdun offensive. After a lull on the Eastern Front, the Russians Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. had resumed the Brusilov Offensive in June and forced Falkenhayn to reorganise the Eastern front, send German divisions to bolster the Austro-Hungarians

Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. had resumed the Brusilov Offensive in June and forced Falkenhayn to reorganise the Eastern front, send German divisions to bolster the Austro-Hungarians Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. Austria-Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. and make limited counter-attacks, which had little effect. In late June and early July the Russians inflicted more defeats and then began to attack the German sector of the Eastern Front at Baranovitchi on 2 July.

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. Austria-Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. and make limited counter-attacks, which had little effect. In late June and early July the Russians inflicted more defeats and then began to attack the German sector of the Eastern Front at Baranovitchi on 2 July.

On 2 July, seven divisions had been sent from the OHL reserve and from the 6th Army to the 2nd Army and another seven were en route by 9 July. On 7 July, Falkenhayn abandoned the plan for a 6th Army counter-offensive against a defeated offensive, for lack of manpower. After the failure of the attack on Fort Souville at Verdun on 12 July, Falkenhayn had ordered a "strict defensive" at Verdun and the transfer of more troops and artillery to the Somme, the first visible strategic effect of the Anglo-French offensive. Falkenhayn adopted a strategy of defeating the offensive on the Somme, to show the French that the German army could not be beaten and that a negotiated peace was inevitable. Casualties on the Somme were so high that by mid-July Falkenhayn had sent the best divisions remaining in the 6th Army, reduced the OHL reserve to one division and begun reorganising the Westheer (Western Army), to allow complete divisions to be transferred to the Somme; the Entente had taken the initiative on the Western Front.

Tactical Developments

On 1 July, the French Sixth Army and the right wing of the Fourth Army had inflicted a considerable defeat on the German 2nd Army. From the Albert–Bapaume road north to Gommecourt, the Fourth Army attack was a disaster, where most of the c. 60,000 British casualties were incurred. Against the wishes of Marshal Joseph Joffre, General Sir Douglas Haig abandoned the offensive north of the road, to reinforce the success in the south. During the Battle of Albert (1–13 July), the Fourth Army pressed forward south of the Albert–Bapaume road, through several intermediate defensive lines towards the German second position. The attacks were hampered by supply routes which became quagmires during rainy periods (lengthening the time for round trips), behind the French XX Corps and the British XIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Walter Congreve), XV Corps (Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Horne) and III Corps (Lieutenant-General William Pulteney).

La Boisselle near the road was captured on 4 July, Bernafay and Caterpillar woods were occupied from 3–4 July and fighting for Trônes Wood, Mametz Wood and Contalmaison took place until early on 14 July. The Germans opposite the Fourth Army were kept disorganised and the British closed to within striking distance of the German second position, a significant but costly victory. The Fourth Army attacks were un-coordinated, tactically crude, wasteful of manpower and gave the Germans an opportunity to concentrate their inferior resources on narrow fronts, multiplying their effect. The loss of c. 60,000 British casualties on 1 July was not repeated. From 2–13 July, the British attacked 46 times and lost c. 25,000 casualties, a change in the rate of loss from c. 60,000–2,083 per day. Around 14 July, Fayolle wrote that the French had taken 12,000 prisoners and 70 guns, the British 7,500 men and 24 guns but that the British had 70,000 men "in the ground" (sic) and were still short of the German second position.

The strain imposed by the Entente attacks after 1 July, led Below to issue an order of the day (2nd Army Order I a 575 secret) on 3 July, forbidding voluntary withdrawals,

The outcome of the war depends on 2nd Army being victorious on the Somme. Despite the current enemy superiority in artillery and infantry we have got to win this battle.... For the time being, we must hold our current positions without fail and improve on them by means of minor counter-attacks. I forbid the voluntary relinquishment of positions.... The enemy must be made to pick his way forward over corpses.

- General von Below, 3 July 1916

Falkenhayn sacked his Chief of Staff, Generalmajor Paul Grünert and General Günther von Pannewitz (XVII Corps), after Grünert allowed Pannewitz to make a withdrawal to the third position south of the Somme, to shorten the corps front; Grünert was replaced by Colonel Fritz von Lossberg. First-class German reinforcements reaching the Somme front, were thrown into the battle piecemeal, which caused higher casualties. Attacks were poorly organised, insufficient time was allowed for reconnaissance and the infantry was inadequately supported by the artillery, which sometimes fired on German troops. German counter-attacks were even less well-organised than their British equivalents and most failed.

Aftermath

On 11 July, GHQ Intelligence had written that,

the admixture of units has been so great... that there are no longer any defined divisional sectors.... The line is now held by a confused mass... whose units appear to have been thrown into [the] front line as stop gaps.

- GHQ Intelligence

OHL reserve was down to one division and that the Germans would have to begin milking divisions for reserves, which led Haig and Rawlinson to believe that attrition was working quickly. Haig thought that German resistance might break within two weeks. The inaccuracy of the intelligence being provided was not known and the assumptions and conclusions were understandable given the evidence. The success of the attack on 14 July increased British optimism, Haig describing it as 'the best day we have had in this war'. Haig and Rawlinson were encouraged by the capture of two German regimental commanders and their staffs and the Fourth Army wrote that, "…the enemy is in confusion and demoralised". Later information showed that the Germans had been forced into expedients, such as sending forward a recruit depot as reinforcements. During 16 July, the Fourth Army concluded that it was necessary to organise another broad front attack and that the Germans would use the respite to reinforce Delville Wood, Longueval and High Wood. Rawlinson hoped that the German could be provoked into costly counter-attacks and concentrated on preparing a new attack for 18 July, the German positions being subjected to a constant bombardment in the meantime. Attempts to arrange the next attack and co-ordinate with a French attack on the north side of the Somme foundered due to the effect of the massed bombardments on the ground, made worse by rain, which turned the ground into deep mud, paralysing movement and the attack did not take place until the night of 21/22 July, being a costly failure. Three days later, the Fourth Army noted that German morale was improving, due mainly to better supply of the front line and by the end of July, British hopes of immediate success had faded.

In 1928, H. A. Jones, the official historian of the RAF wrote that the battle showed that infantry co-operation would be a permanent feature of British air operations. Recognition flares had proved effective, although there had been too few and because of infantry were reluctant to risk revealing their positions to German artillery observers. Scheduled illumination was a failure and infantry began to wait for a call from the contact aeroplane, by signal lamp or by klaxon. RFC observers reported that direct observation was the most effective method and that flying low enough to be fired on worked best, although this led to many aircraft being damaged and one lost to a British shell. Artillery-observation was hampered by bad weather but the rolling countryside led to constant demands for sorties for counter-battery fire; when the weather grounded the RFC, attacks could fail for lack of observation.

Aircrew photographed the attack front, reported on the condition of wire and trenches, assessed the opposition, linked headquarters and front line and then joined in by bombing and strafing from low altitude. Artillery-observation led to the neutralisation of German batteries, destruction of trenches and strong points and fleeting opportunities to bombard German troops in the open. British aircraft caused a feeling of defencelessness among German troops and deprived them of the support of the Fliegertruppen, leaving them dependent on wasteful unobserved area artillery-fire, while being vulnerable to British aircrew seeing muzzle-flashes giving away battery positions. Reinforcements of fighters were slow to arrive on the Somme and prevented the Fliegertruppen from challenging Anglo-French aerial dominance. The morale of British troops was correspondingly increased, that German artillery could not conduct observed shoots against them and that German troops could not move against them without being seen by the RFC.

In 1938, Wilfrid Miles, the official historian wrote that it had been a mistake for the attacking divisions to be held back from exploiting the victory straight away, since there appeared to be no Germans left to oppose the 7th and 3rd divisions by 10:00 a.m. when several officers walked forward unopposed. Watts wanted to send the fresh 91st Brigade into High Wood but had orders to wait for the cavalry; Haldane was prevented by the Fourth army HQ from using the 76th Brigade for a pursuit, having to keep it ready for German counter-attacks. Miles wrote that authority could have been delegated to the divisional commanders on the spot, since the 33rd Division had already arrived at Montauban and a vigorous pursuit would have made the prospects for the cavalry much more favourable when they managed to reach the front line. It may even have been possible for the infantry to penetrate High Wood and dig in on the ridge, to threaten Delville Wood and Pozières, rather than the two-month slog it actually took.

In a 2001 study, Snowden wrote that the 21st Division was successful because of the weight and accuracy of the British bombardment enabled the night assembly to take place in safety. The German wire and trenches were destroyed and the few German survivors were relatively easily overcome. Despite the destructive effect of the artillery, Snowden wrote that it was more significant that inexperienced infantry had shown a capacity for tactical evolution. The 110th Brigade had advanced faster than the 7th Division, captured all its objectives and held them against the unexpectedly large counter-attacks that lasted from 10:00–2:00 p.m. The coincidence of the German relief of the 123rd Division by the 7th Division had meant that three regiments of fresh troops (about 5,000 infantry) were available. The capture of 0.25 sq mi (0.65 km2) of ground cost 3,000 casualties, the highest divisional losses in the attack but more ground could have been taken, had exploitation been allowed before the German counter-attacks began.

In 2005, Prior and Wilson called the success of the attack a considerable achievement and showed that if an objective could be bombarded by enough shells, it could be captured but that this had been only the first stage in the Fourth Army plan, which had extravagant ambitions to be fulfilled by infantry and cavalry, beyond the terrain devastated by the artillery. Rawlinson had realised what the advance on 14 July had been possible because of the accuracy and extent of the bombardment, which had smashed the German defences, obliterated the wire and exhausted the German infantry by concussion, where they had not been killed. Prior and Wilson wrote that the British failed to study the reasons for the results not reaching expectations and that this meant that Rawlinson and Haig had not learned from their mistakes. J. P. Harris, in 2009, wrote that the Fourth Army made solid gains on 14 August, with fewer casualties than on 1 July at much greater cost to the Germans. When the cavalry finally managed to attack in the evening, it inflicted about 100 casualties for eight losses. In two weeks the British had advanced beyond the German second position, south of the Albert–Bapaume road and faced only scanty field defences. The victory was a false dawn, because the German 2nd Army improvised defences and converted High Wood and Delville Wood into fortresses.

Piecemeal reinforcement of the German defences since 1 July, had become administratively chaotic, an example being the crowding of the field kitchens of five regiments onto ground north of Courcelette, having to share the Stockachergraben, the last open communication trench, to carry food forward at night. On 17 July, Below added to his secret order of 3 July,

Despite my ban on the voluntary relinquishment of positions, apparently certain sectors have been evacuated without an enemy attack. Every commander is responsible for ensuring that his troops fight to the last man to defend the sector for which he is responsible. Failure to do so will lead to Court Martial proceedings. This Army Order is to be made known to all commanders.

- Below, 17 July 1916

Staff officers of the German IV Corps wrote a report on the experience of fighting the British in July, which dwelt on the details of the defensive battle, in which emphasis was given to fortification, the co-operation of infantry and artillery and the necessity for maintaining communications, using every means possible, to overcome the chaos of battle. British infantry had learnt much since the Battle of Loos (25 September – 14 October 1915) and attacked vigorously, which was assumed to be due to the confidence of the infantry in their overwhelming artillery. British tactical leadership was considered to be lacking and men tended to surrender if surrounded. Units were assembled close together and suffered many losses to German artillery but the British showed skill in rapid consolidation of captured ground and tenacity in defence, small parties with automatic weapons being most difficult to overcome. German infantry remained confident that they were superior to British infantry but British medium and heavy artillery outnumbered German guns and the quality of its ammunition had improved. German infantry and artillery positions were subjected to methodical bombardment, villages just behind the front line and ground affording natural cover were continuously bombarded and artillery registration and aim were assisted by organised aerial observation, aircraft also frequently being used to bomb villages at night. British frontal attacks by cavalry against infantry and had suffered "heavy losses", reflecting badly on the tactical knowledge of British higher commanders.

Ill-prepared German attacks almost always failed and care needed to be taken to understand the difference between hasty counter-attacks soon after the loss of ground with troops on the spot and organised counter-attacks ordered by commanders further back, which needed more troops from reserve and deliberate preparation because of the inevitable delays in movement, communication and the preparation of artillery-support, which could not be hurried. Organised counter-attacks worked best with fresh troops, advancing behind a creeping barrage, lifting according to a timetable. Attacks into woods needed a different formation than advances by skirmish lines in open country, one line being followed by small columns and flame-throwers had been ineffective because of the difficulty of carrying such heavy equipment through obstructions and the lack of view and should be reserved for defined objectives which had been studied beforehand.

Casualties

The Fourth Army had 9,194 casualties, 1,159 in the 9th Division, 2,322 in the 3rd Division, 2,819 in the 7th Division and 2,894 in the 21st Division. BIR 16 had 2,300 casualties on 14 July, of the 2,559 losses it suffered on the Somme that month. In July, British casualties on the Somme were 158,786, French losses were 49,859 (a combined total of 208,645 casualties) and the German 2nd Army suffered 103,000 losses, 49.4 percent of Allied casualties.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles "World War", "World War I", and "Battle of Bazentin Ridge", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.