World War I (1914-1918)

Battle of Fromelles

The Battle of Fromelles (Battle of Fleurbaix, Schlacht von Fromelles 19–20 July 1916) was a British military operation on the Western Front during the First World War, subsidiary to the Battle of the Somme.

General Headquarters (GHQ) of the British The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. Expeditionary Force (BEF) had ordered the First and Second armies to prepare attacks to support the Fourth Army on the Somme 50 mi (80 km) to the south, to exploit any weakening of the German

The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. Expeditionary Force (BEF) had ordered the First and Second armies to prepare attacks to support the Fourth Army on the Somme 50 mi (80 km) to the south, to exploit any weakening of the German The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. defences opposite. The attack took place 9.9 mi (16 km) from Lille, between the Fauquissart–Trivelet road and Cordonnerie Farm, an area overlooked from Aubers Ridge to the south. The ground was low-lying and much of the defensive fortification by both sides consisted of breastworks, rather than trenches.

The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. defences opposite. The attack took place 9.9 mi (16 km) from Lille, between the Fauquissart–Trivelet road and Cordonnerie Farm, an area overlooked from Aubers Ridge to the south. The ground was low-lying and much of the defensive fortification by both sides consisted of breastworks, rather than trenches.

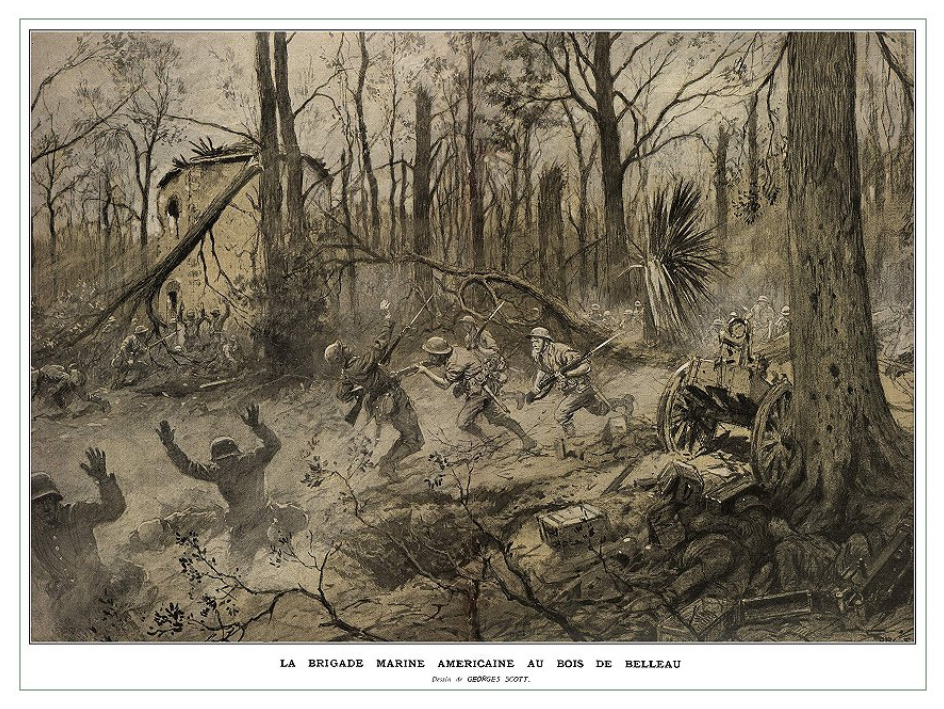

The operation was conducted by XI Corps of the First Army with the 61st Division and the 5th Australian Division, Australian Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. In 1770, the British explorer James Cook mapped and claimed the east coast of Australia for Great Britain, and the First British Fleet arrived in 1788 to establish the penal colony of New South Wales. Australia sent many thousands of troops to fight for Britain during WWI. Imperial Force (1st AIF) against the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division, supported by two flanking divisions of the German 6th Army. Preparations for the attack were rushed, the troops involved lacked experience in trench warfare and the power of the German defence was significantly underestimated, the attackers being outnumbered 2:1. The advance took place in daylight on a narrow front against defences overlooked by Aubers Ridge, which left German artillery on either side free to fire into the flanks of the attack. A renewal of the attack by the 61st Division early on 20 July was cancelled, after it was realised that German counter-attacks had already forced a retirement by the Australian troops to the original front line.

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. In 1770, the British explorer James Cook mapped and claimed the east coast of Australia for Great Britain, and the First British Fleet arrived in 1788 to establish the penal colony of New South Wales. Australia sent many thousands of troops to fight for Britain during WWI. Imperial Force (1st AIF) against the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division, supported by two flanking divisions of the German 6th Army. Preparations for the attack were rushed, the troops involved lacked experience in trench warfare and the power of the German defence was significantly underestimated, the attackers being outnumbered 2:1. The advance took place in daylight on a narrow front against defences overlooked by Aubers Ridge, which left German artillery on either side free to fire into the flanks of the attack. A renewal of the attack by the 61st Division early on 20 July was cancelled, after it was realised that German counter-attacks had already forced a retirement by the Australian troops to the original front line.

On 19 July, General Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of the General Staff, had judged the British attack to be a long-anticipated offensive against the 6th Army. The attack gained no ground but inflicted some losses on the Germans and recent research has asserted that troops were held back on the XI Corps front. The next day, when the effect of the attack was known and a captured operation order from XI Corps revealed the limited intent of the operation, Falkenhayn ordered troops to be withdrawn from the Souchez–Vimy area, 20 mi (32 km) from Fromelles; troops were only withdrawn opposite the XI Corps from four to nine weeks later. The attack was the début of the AIF on the Western Front and the Australian War Memorial described the battle as "the worst 24 hours in Australia's entire history". Of 7,080 BEF casualties, 5,533 losses were incurred by the 5th Australian Division; German losses were 1,600–2,000 men, with 150 men taken prisoner.

Background

The course of the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916) had led the British GHQ on 5 July to inform the commanders of the three other British armies that the German defences from the Somme north to the Ancre river might soon fall. The First and Second army commanders were required to choose places to penetrate the German defences, if the attacks on the Somme continued to make progress. Any gaps made were to be widened to exploit the weakness and disorganisation of the German defence. The Second Army commander, General H. Plumer was occupied by preparations for an offensive at Messines Ridge but could spare one division for a joint attack with the First Army at the army boundary. On 8 July, the First Army commander General Charles Monro, ordered the IX Corps commander Lieutenant-General Richard Haking to plan a two-division attack; Haking proposed to capture Aubers Ridge, Aubers and Fromelles but the next day Monro dropped Aubers Ridge from the attack, as he and Plumer had concluded that with the troops available, no great objective could be achieved.

On 13 July, after receiving intelligence reports that the Germans had withdrawn approximately nine infantry battalions from the Lille area from 9–12 July, GHQ informed the two army commanders that a local attack was to be carried out at the army boundary around 18 July, to exploit the depletion of the German units in the vicinity. Haking was ordered to begin a preliminary bombardment, intended to appear to be part of a large offensive, while limiting an infantry attack to the German front line. On 16 July discussions about the attack resumed, as the need for diversions to coincide with operations on the Somme had diminished when the big victory of Bazentin Ridge (14 July 1916) had not led to a general German collapse. Sir Douglas Haig the Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, did not want the attack to take place unless the local commanders were confident of success and Monro and Haking opposed postponement or cancellation of the attack. The weather had been dull on 15 July and rain began next day, soon after Monro and Haking made the decision to proceed with the attack. Zero hour for the main bombardment was postponed because of the weather and at 8:30 a.m., Haking delayed the attack for at least 24 hours; after thinking about cancelling the attack, Monro postponed it until 19 July.

British Offensive Preparations

The Second Army provided the 5th Australian Division, the artillery of the 4th Australian Division and heavy guns and trench mortars to XI Corps, to participate in an attack from the Fauquissart–Trivelet road to La Boutillerie with the 31st Division and 61st Division. A shortage of artillery and the lack of training and experience in the Australian divisional artilleries and some of the heavy batteries, led to the attack front being reduced to 4,000 yd (3,700 m) between the Fauquissart–Trivelet road and Delangre Farm. The ground to be attacked was waterlogged, flat and easily overlooked from Aubers Ridge, behind the German front line to the south. The 39th Division and 31st Division moved their boundaries north as the 61st Division concentrated along its attack front from the Fauquissart–Trivelet road to Bond Street. The 20th (Light) Division moved its boundary south to Cordonnerie Farm to take over the left of the 5th Australian Division, which concentrated the divisional frontage from Cordonnerie Farm to Bond Street. The twelve attacking battalions were supported by more artillery than at the Battle of Aubers Ridge in May 1915, when a similar number of battalions attacked in the same area. More ammunition was available than in 1915 and trench mortars were added to the artillery for wire cutting. With support from First Army artillery to the south, 296 field guns and 78 heavy guns were ready, which gave a greater concentration of heavy artillery than that of the Fourth Army on the first day of the Somme.

After several rain delays, visibility increased on 18 July and the artillery bombardment proceeded. The shelling of the German front at La Bassée was repeated and the German artillery retaliated. Overnight, British patrols reported no movement in the German lines, which appeared to be weakly held. German covering parties stopped Australian raiders on the right flank of the 5th Australian Division front, where the wire appeared to be intact except for gaps on the left. There was a haze during the morning of 19 July but the time of artillery zero hour was fixed for 11:00 a.m., ready for the infantry attack at 6:00 p.m. A special heavy artillery bombardment began on the Sugarloaf at 2:35 p.m., by which time a German counter-bombardment was falling all along the attack front, causing casualties to the Australians and the field artillery crews of the 61st Division at Rue Tilleloy. Several ammunition dumps were exploded and the decoy lifts by the British artillery failed to deceive the Germans. The Australian and British infantry began to move into no man's land at 5:30 p.m.

British Plan of Attack

The German salient at Fromelles contained some higher ground facing north-west, known as the Sugarloaf. The small size and height of the salient gave the Germans observation of no man's land on either flank. The 5th Australian Division (Major-General James McCay) was to attack the left flank of the salient by advancing south as the 61st Division attacked on the right flank from the west. Each division was to attack with three brigades in line, with two battalions from each brigade in the attack and the other two in reserve, ready to take over captured ground or to advance further. Haking issued the attack orders on 14 July, when wire cutting began along the XI Corps front. It was intended that the bombardment would inflict mass casualties on the German infantry, reducing them to a "state of collapse". The British infantry were to assemble as close to the German lines as possible, no man's land being 100–400 yd (91–366 m) wide, before the British artillery fire was lifted from the front line; the infantry would rush the surviving Germans while they were disorganised and advance to the German second line. Heavy artillery began registration and a slow bombardment on 16 July and two days of bombardment began either side of La Bassée canal as a diversion. The main bombardment was to begin at midnight on 17/18 July for seven hours (more rain forced a postponement). Over the final three hours, the artillery was to lift and the infantry show bayonets and dummy figures several times, to simulate an infantry advance, then the artillery was to resume bombardment of the front line to catch the German infantry out of cover.

German Defensive Preparations

General Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of the General Staff had ordered a construction programme on the Western Front in January 1915, to make it capable of being defended indefinitely by a small force against superior numbers. An elaborate, carefully sited and fortified front position was built behind fields of barbed wire, with camouflaged concrete machine-gun nests and a second trench close behind the front trench to shelter the trench garrison during bombardments. To evade Allied artillery-fire intended to obstruct the movement of reinforcements from the new rear defences, communication trenches were built. The front position was to be held at all costs as the main line of resistance but in May 1915, Falkenhayn ordered a reserve position to be built along the Western Front, 2,000–3,000 yd (1,800–2,700 m) behind the front position, out of range of enemy field artillery. To contain a breakthrough, the second position was to be occupied opposite a sector broken into and serve as a jumping-off point for by counter-attacking troops. If counter-attacks failed to recover the front line, the rear position could be connected to the remaining parts of the front line on either side.

The construction programme was a huge undertaking, which took until autumn 1915 and had several opponents, notably the 6th Army commander Crown Prince Rupprecht, who claimed that a rear position would undermine the determination of soldiers to stand their ground. The front of the 6th Army had been quiet since the Battle of Loos (25 September – 14 October 1915) and in July 1916, the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division held a 4.5 mi (7.2 km) stretch of the front with four regiments, from east of Aubers village, north to a point near Bois-Grenier, each regiment having one battalion in the front line, one in support and one in reserve. On one regimental front there were 75 shelters with 9–12 in (230–300 mm) of concrete protection. After a British gas attack opposite Neuve Chapelle and Fauquissart late on 15 July, German artillery bombarded the British front line and a raid by 100 troops of Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 21 on the Australian lines, caused nearly 100 casualties and took three prisoners for a loss of 32 casualties.

Aftermath

Neither division was well prepared for the attack; the 61st Division had disembarked in France French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. in late May 1916, after delays in training caused by equipment shortages and the supplying of drafts to the 48th Division. The British entered the front line for the first time on 13 June and every man not part of the attack spent from 16 to 19 July removing poison gas cylinders from the front line when the discharge planned for 15 July was suspended due to the wind falling; 470 cylinders were removed before the work was stopped because the men were exhausted. The 5th Australian Division had arrived in France only days before the attack and had relieved the 4th Australian Division on the right flank of the Second Army by 12 July. The Australian divisional artillery and some of the heavy artillery had no experience of Western Front conditions and as I Anzac Corps prepared to move south to the Somme front a considerable shuffling of divisions had taken place, which hampered preparations for the attack.

French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. in late May 1916, after delays in training caused by equipment shortages and the supplying of drafts to the 48th Division. The British entered the front line for the first time on 13 June and every man not part of the attack spent from 16 to 19 July removing poison gas cylinders from the front line when the discharge planned for 15 July was suspended due to the wind falling; 470 cylinders were removed before the work was stopped because the men were exhausted. The 5th Australian Division had arrived in France only days before the attack and had relieved the 4th Australian Division on the right flank of the Second Army by 12 July. The Australian divisional artillery and some of the heavy artillery had no experience of Western Front conditions and as I Anzac Corps prepared to move south to the Somme front a considerable shuffling of divisions had taken place, which hampered preparations for the attack.

The limited nature of the attack quickly became obvious to the German commanders. A German assessment of 16 December 1916, called the attack "operationally and tactically senseless" and prisoner interrogations revealed that the Australian troops were physically imposing but had "virtually no military discipline" and "no interest in soldiering as it was understood in Europe". A German report on 30 July 1916, recorded that captured officers said that the Australians made a fundamental mistake in trying to hold the German second trench, rather than falling back to the front trench and consolidating. When the 15th Australian Brigade was pinned down in no man's land, the continuity of the attack broke down and lost protection against flanking fire from the right, which enabled German troops to counter-attack, regain the first trench and cut off the Australian troops further forward.

A communiqué, released to the press by British GHQ, was not favourably received by the Australians. "Yesterday evening, south of Armentières, we carried out some important raids on a front of two miles in which Australian troops took part. About 140 German prisoners were captured". Australian losses, and doubts about the judgement of higher commanders, damaged relations between the AIF and the British, with further doubts about the reliability of British troops spreading in Australian units. In 2008, Grey wrote that McCay also made errors in judgement that contributed to the result, citing McCay's order not to consolidate the initial gains and that poor planning, ineffective artillery support and Australian lack of experience of Western Front conditions, contributed to the failure. A number of senior Australian officers were removed after the débâcle and the 5th Australian Division remained incapable of offensive action until late summer, when it began trench-raiding. In October the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division, with morale high after the defensive success at Fromelles, was sent to the Somme front and never recovered from the ordeal; Bavarian Reserve Regiment 16 spent ten days in the line and lost 1,177 casualties.

In 2012, Michael Senior wrote that the objective of the attack was contained in the First Army Operational Order 100 (15 July);

...to prevent the enemy from moving troops Southwards, to take part in the main battle

- Senior

Haking had ordered that the troops due to attack were to be told that;

The Commander in Chief [Haig] had directed XI Corps to attack the enemy in front of us, capture his front line system of trenches, and thus prevent him from reinforcing his troops to the South.

- AWM 4 1/22/4 pt. 1 in Senior

Senior wrote that historians generally judged the attack to have failed to prevent German troops being moved south to the Somme, Wilfid Miles, the British official historian, writing that the IX Reserve and the Guard Reserve corps had been sent. Peter Pedersen wrote that the Germans knew that Fromelles was a decoy and sent the reserves to the Somme and in the Australian official history Charles Bean wrote that the attack showed the Germans that they were free to withdraw troops. In 2007, Paul Cobb wrote that the Germans were not deterred from sending troops to reinforce the Somme. Senior wrote that there was evidence that the transfer of troops to the south was delayed. A German intelligence officer of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division wrote on 20 July,

There are no signs of any immediate repetition of the enemy attack....However, judging by the general situation, a new push is not impossible.

- AWM 27 111/13 in Senior

A Bavarian document discovered in 1923 related that

An order was captured declaring that the object of the attack was to keep German troops engaged in the sector so as to keep pressure from the Somme...a repetition of these attacks is therefore to be expected.

- CAB 45/172 in Senior

Bean wrote in 1930 that the Bavarians might have doubted that the British would sacrifice 7,000 men as a decoy.

The IX Reserve and Guard Reserve corps had been moved from the Souchez–Vimy area, 20 mi (32 km) from Fromelles, well outside the XI Corps sector. Troops kept in the Loos–Armentières sector opposite the corps for four weeks after 19 July, were held back as a precaution. German records show that eight divisions were between Loos and Armentières on 1 July and that two were sent to the Somme by 2 July, long before the Fromelles attack and the other six divisions stayed opposite XI Corps for five to nine weeks after 19 July. Had divisions moved earlier, the Battle of Pozières (23 July – 3 September), might have cost I Anzac Corps far more than the 23,000 casualties that it suffered. Senior concluded that German troops had been retained opposite the XI Corps because of the attack at Fromelles.

Casualties

The battle caused one of the greatest numbers of Australian deaths in action in 24 hours, surpassed only at the Battle of Bullecourt in 1917. The 5th Australian Division lost 5,513 casualties, 2,000 men in the 8th Brigade, 1,776 men of the 15th Brigade, 1,717 men in the 14th Brigade and 88 men from the divisional engineers; two battalions had so many casualties that they had to be rebuilt. Of 887 personnel from the 60th Battalion, only one officer and 106 other ranks survived unwounded and the 32nd Battalion suffered 718 casualties. The 31st Battalion had 544 casualties and the 32nd Battalion lost 718 men killed and wounded. The 61st Division was already under strength before the battle, engaged half as many men as the 5th Australian Division and lost 1,547 casualties. German casualties in the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division were 1,600–2,000 men. Allied soldiers killed in the area that was re-taken by the Germans, were buried shortly after the battle. The burial pits were photographed from a British reconnaissance aircraft on 21 July but marked as dugouts or trench-mortar positions. The bodies were taken by narrow gauge trench railway on 22 July and buried in eight 10 m × 2.2 m × 5 m (32.8 ft × 7.2 ft × 16.4 ft) pits.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles "World War", "World War I", and "Battle of Fromelles", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.