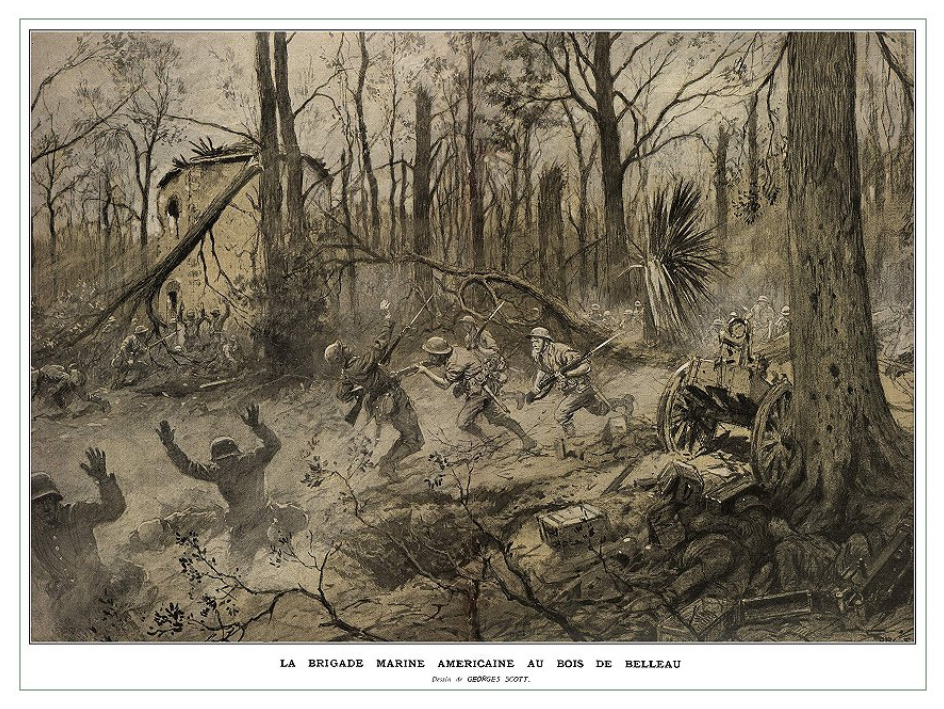

World War I (1914-1918)

Battle of Flers–Courcelette

The Battle of Flers–Courcelette (15–22 September 1916) was fought during the Battle of the Somme in France, by the French Sixth Army and the British Fourth Army and Reserve Army, against the German 1st Army, during the First World War.

The Anglo-French attack of 15 September began the third period of the Battle of the Somme but by its conclusion on 22 September, the strategic objective of a decisive victory had not been achieved. The infliction of many casualties on the German The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. front divisions and the capture of the villages of Courcelette, Martinpuich and Flers had been a considerable tactical victory but the German defensive success on the British

The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. front divisions and the capture of the villages of Courcelette, Martinpuich and Flers had been a considerable tactical victory but the German defensive success on the British The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. right flank, made exploitation and the use of cavalry impossible. Tanks were used in battle for the first time in history and the Canadian

The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. right flank, made exploitation and the use of cavalry impossible. Tanks were used in battle for the first time in history and the Canadian Canada is a country in North America. Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the British North America Act, 1867, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into World War I. Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps, which played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major engagements of the war. Corps and the New Zealand

Canada is a country in North America. Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the British North America Act, 1867, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into World War I. Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps, which played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major engagements of the war. Corps and the New Zealand The Dominion of New Zealand was the historical successor to the Colony of New Zealand. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire. Subsequently, a series of conflicts between the colonial government and Māori tribes resulted in the alienation and confiscation of large amounts of Māori land. New Zealand became a dominion in 1907; it gained full statutory independence in 1947, retaining the monarch as head of state. Division fought for the first time on the Somme. On 16 September, Jagdstaffel 2, a specialist fighter squadron, began operations with five new Albatros D.I fighters, which were capable of challenging British air supremacy for the first time since the beginning of the battle.

The Dominion of New Zealand was the historical successor to the Colony of New Zealand. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire. Subsequently, a series of conflicts between the colonial government and Māori tribes resulted in the alienation and confiscation of large amounts of Māori land. New Zealand became a dominion in 1907; it gained full statutory independence in 1947, retaining the monarch as head of state. Division fought for the first time on the Somme. On 16 September, Jagdstaffel 2, a specialist fighter squadron, began operations with five new Albatros D.I fighters, which were capable of challenging British air supremacy for the first time since the beginning of the battle.

The attempt to advance deeply on the right and pivot on the left failed but the British gained about 2,500 yd (2,300 m) in general and captured High Wood, moving forward about 3,500 yd (3,200 m) in the centre, beyond Flers and Courcelette. The Fourth Army crossed Bazentin Ridge, which exposed the German rear-slope defences beyond to ground observation and on 18 September, the Quadrilateral, where the British advance had been frustrated on the right flank, was captured. Arrangements were begun immediately to follow up the tactical success which, after supply and weather delays, began on 25 September at the Battle of Morval; continued by the Reserve Army next day at the Battle of Thiepval Ridge. In September, the German armies on the Somme lost about 130,000 casualties, the most costly month of the battle. Combined with the losses at Verdun and on the Eastern Front, the German Empire was brought closer to military collapse than at any time before the autumn of 1918.

Strategic Developments

Franco-British

At the beginning of August, optimistic that the Brusilov Offensive (4 June – 20 September) on the Eastern Front in Russia Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire., would continue to absorb German and Austro-Hungarian

Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire., would continue to absorb German and Austro-Hungarian Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. Austria-Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. reserves and that the Germans had abandoned the Battle of Verdun, General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, advocated to the War Committee in London, that relentless pressure be kept on the German armies in France

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. Austria-Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. reserves and that the Germans had abandoned the Battle of Verdun, General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, advocated to the War Committee in London, that relentless pressure be kept on the German armies in France French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. for as long as possible. Haig had hoped that the delay in producing tanks had been overcome and that enough would be ready in September. Despite the small numbers of tanks available and the limited time for the training of crews, Haig planned to use them in the mid-September battle being planned with the French, in view of the importance of the general Allied offensive being conducted on the Western Front in France, on the Italian front by Italy

French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. for as long as possible. Haig had hoped that the delay in producing tanks had been overcome and that enough would be ready in September. Despite the small numbers of tanks available and the limited time for the training of crews, Haig planned to use them in the mid-September battle being planned with the French, in view of the importance of the general Allied offensive being conducted on the Western Front in France, on the Italian front by Italy The Kingdom of Italy was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946. The state resulted from a decades-long process, the Risorgimento, of consolidating the different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state. That process was influenced by the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered Italy's legal predecessor state. against the Austro-Hungarians and by General Aleksei Brusilov in Russia, which could not continue indefinitely. Haig believed that the German defence of the Somme front was weakening and that by mid-September might collapse altogether.

The Kingdom of Italy was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946. The state resulted from a decades-long process, the Risorgimento, of consolidating the different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state. That process was influenced by the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered Italy's legal predecessor state. against the Austro-Hungarians and by General Aleksei Brusilov in Russia, which could not continue indefinitely. Haig believed that the German defence of the Somme front was weakening and that by mid-September might collapse altogether.

By September, Ferdinand Foch the commander of Groupe d'armées du Nord (GAN) and co-ordinator of the Somme offensive, had stopped trying to get the armies on the Somme (Tenth, Sixth, Fourth and Reserve) to attack simultaneously, which had proved impossible and instead make separate sequenced attacks, successively to envelop the German fortifications. Foch wanted to increase the size and tempo of attacks, to weaken the German defence and achieve rupture, a general German collapse. Haig had been reluctant to participate in August, when the Fourth Army was not close enough to the German third position to make a general attack practicable. The main effort was being made north of the Somme by the British and Foch had to acquiesce, while the Fourth Army closed up to the third position. To help the Fourth Army, the Reserve Army was to resume attacks against Thiepval and for the first time attack into the Ancre river valley, the Fourth Army was to capture the German intermediate and second positions from Guillemont to Martinpuich and then the third position from Morval to le Sars, as the Sixth Army attacked the intermediate line from Le Fôret to Cléry, then the third position from the Somme to Rancourt. On the south side of the river, the Tenth Army would commence its postponed attack from Barleux to Chilly.

German

On 28 August, General Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the General Staff of Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, supreme army command), simplified the German command structure on the Western Front by establishing two army groups. Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht controlled the 6th Army, 1st Army, 2nd Army and 7th Army, from Lille to the boundary of Heeresgruppe Deutscher Kronprinz, from south of the Somme battlefield to beyond Verdun. Armeegruppe Gallwitz-Somme was dissolved and General Max von Gallwitz reverted to the command of the 2nd Army. The emergency in Russia caused by the Brusilov Offensive, the entry of Rumania into the war and French counter-attacks at the Verdun, put further strain on the German army. Falkenhayn was sacked from the OHL on 28 August and replaced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff. This Third OHL ordered an end to attacks at Verdun and the despatch of troops to Rumania and the Somme front.

Tactical Developments

Flers is a village 9 mi (14 km) north-east of Albert, 4 mi (6.4 km) south of Bapaume, to the east of Martinpuich, west of Lesbœufs and to the north-east of Delville Wood. The village is on the D 197 from Longueval to Ligny Thilloy. In 1916, the village was defended by the Switch Line, Flers Trench on the western outskirts, Flea Trench and Box and Cox were behind the village in front of Gird Trench and Gueudecourt. Courcelette is near the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road, 7 mi (11 km) north-east of Albert, to the north-east of Pozières and south-west of Le Sars.

Since 1 July, the BEF GHQ tactical instructions issued on 8 May had been added to but without a general tactical revision. Attention had been drawn to matters which had been neglected in the heat of battle, such as the importance of infantry skirmish lines being followed by small columns, captured ground being mopped up, avoiding the tendency to rely on hand-grenades (bombs) at the expense of the rifle, consolidation of captured ground, the benefit of machine-gun fire from the rear, the use of Lewis guns on the flanks and in outposts and the value of Stokes mortars for close-support. The wearing-out battles since late July and events elsewhere, led to a belief that the big Allied attack planned for mid-September would have more than local effect.

A general relief of the German divisions on the Somme was completed in late August; the British assessment of the number of German divisions available as reinforcements was increased to eight. GHQ Intelligence considered a German division on the British front was worn-out after 4 1⁄2 days and that German divisions had to spend an average of twenty days in the line before relief. Of six more German divisions moved to the Somme by 28 August, only two had been known to be in reserve, the other four having been moved from quiet sectors without warning.

Hindenburg issued new tactical instructions in The Defensive Battle which ended the emphasis on holding ground at all costs and counter-attacking every penetration. The purpose of the defensive battle was defined as allowing the attacker to wear out their infantry, using methods which conserved German infantry. Manpower was to be replaced by machine-generated firepower, using equipment built in a competitive mobilisation of domestic industry under the Hindenburg Programme, the policy rejected by Falkenhayn as futile, given the superior resources of the coalition fighting the Central Powers. Defensive practice on the Somme had already been changing towards defence in depth, to nullify Anglo-French firepower and the official adoption of the practice marked the beginning of modern defensive tactics. Ludendorff also ordered the building of the Siegfriedstellung, a new defensive system 15–20 mi (24–32 km) behind the Noyon Salient (which became known as the Hindenburg Line) to make possible a withdrawal while denying the Franco-British the chance to fight a mobile battle.

Since July, German infantry had been under constant observation from aircraft and balloons, which directed huge amounts of artillery-fire accurately onto their positions and made many machine-gun attacks on German infantry. One regiment ordered men in shell-holes to dig fox-holes or cover themselves with earth for camouflage and sentries were told to keep still, to avoid being seen. The German air effort in July and August had mostly been defensive, which led to much criticism from the infantry and ineffectual attempts to counter Anglo-French aerial dominance, dissipating German air strength to no effect. Anglo-French artillery observation aircraft was considered brilliant, annihilating German artillery and attacking infantry from very low altitude, causing severe anxiety among German troops, who treated all aircraft as Allied and came to believe that Anglo-French aircraft were armoured.

Redeployment of German aircraft backfired, many losses being suffered for no result, which further undermined relations between the infantry and Die Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches (Imperial German Flying Corps). German artillery units preferred direct protection of their batteries to artillery observation flights, which led to more losses as the German aircraft were inferior to their opponents as well as outnumbered. Slow production of German aircraft exacerbated equipment problems and German air squadrons were equipped with a motley of designs, until the arrival in August of Jagdstaffel 2 (Hauptmann [Captain] Oswald Boelcke), equipped with the Halberstadt D.II, which began to restore a measure of air superiority in September and the first Albatros D.Is, which went into action on 17 September.

Invention of the Tank

Before 1914, inventors had designed armoured fighting vehicles and one had been rejected by the Austro-Hungarian army in 1911. In 1912, L. E. de Mole submitted plans to the War Office for a machine which foreshadowed the tank of 1916, that was also rejected and in Berlin an inventor demonstrated a land cruiser in 1913. By 1908, the British army had adopted vehicles with caterpillar tracks to move heavy artillery and in France, Major E. D. Swinton RE heard of the cross-country, caterpillar-tracked Holt tractor in June 1914. In October, Swinton thought of a machine-gun destroyer, that could cross barbed wire and trenches and at GHQ discussed it with Major-General G. H. Fowke, the army chief engineer, who passed this on to Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice Hankey, the Secretary of the War Council but this had evoked little interest by January 1915. Swinton persuaded the War Office to set up an informal committee, which in February watched a demonstration of a Holt tractor pulling a weight of 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) over trenches and barbed wire, the performance of which was judged unsatisfactory.

Independent of Swinton, Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty had in October 1914, asked for an adaptation of a 15-inch howitzer tractor for trench crossing. In January 1915, Churchill had written to the Prime Minister, on the subject of an armoured caterpillar tractor to crush barbed wire and cross trenches and on 9 June, a vehicle with eight driving wheels and bridging gear was demonstrated to the War Office committee. The equipment failed to cross a double line of trenches 5 ft (1.5 m) wide and the experiment was abandoned. In parallel to these explorations, on 19 January 1915, Churchill ordered Commodore F. M. Seuter, Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) to conduct experiments with steamrollers and in February, Major T. G. Hetherington RNAS, showed Churchill designs for a land battleship. Churchill set up a Landships Committee, chaired by Eustace Tennyson d'Eyncourt the Director of Naval Construction, to oversee the creation of an armoured vehicle to crush wire and cross trenches.

In June 1915, Sir John French, commander of the BEF found out about the ideas put forward by Swinton for caterpillar machine-gun destroyers. French sent the memoranda to the War Office, which in late June began to liaise with the Landships Committee at the Admiralty and specified the characteristics of the desired vehicle. Churchill had relinquished his post in the War Committee but lent his influence to the experiments and building of the tanks. By August, Swinton was able to co-ordinate the War Office specifications for the tanks, Admiralty design efforts and manufacture by the Ministry of Munitions. An experimental vehicle built by Fosters of Lincoln was tested in secret at Hatfield on 2 February 1916 and the results were considered so good that 100 more vehicles of the mother design and a prototype of the Mark I tank were ordered.

In March 1916, Swinton was given command of the new Heavy Section, Machine-Gun Corps, raised from 20 Squadron, RN Armoured Car Division, with an establishment of six companies with 25 tanks each, crewed by 28 officers and 255 men. Training began in great secrecy in June at Elveden in Suffolk, as soon as the first Mark I tank arrived. Two types of Mark I tank had been designed, male tanks, with a crew of eight, two 6-pounder guns and three Hotchkiss 8 mm machine-guns, a maximum speed of 3.7 mph (6.0 km/h) and a tail (two wheels at the rear to help with steering and to reduce the shock of crossing broken ground). Female tanks were similar in size, weight, speed and crew and were intended to defend the males against a rush by opposing infantry, with their armament of four Vickers and one Hotchkiss machine-gun and a much larger allotment of ammunition.

Aftermath

In 2003, Sheffield wrote that the verdict of Wilfrid Miles, the official historian was accurate, the Germans "...had been dealt a severe blow" but the attack "fell far short of the desired achievement". The British advanced 2,500 yd (2,300 m) and at Flers got forward 3,500 yd (3,200 m). The German defence had almost collapsed and the British captured 4,500 yd (4,100 m) of the third position, taking about double the amount of ground taken on 1 July for about half the casualties. The Germans recovered quickly and the Fourth Army was not able to exploit the success due to exhaustion and disorganisation; on the right flank the French took little ground. The battle was a moderately successful set-piece attack by 1916 standards and the British had reached a good position to attack the rest of the German third position. Sheffield wrote that the plan had been too ambitious and mistakes were made in the use of artillery and tanks; given the inexperience of the BEF, a better result would have been surprising.

Prior and Wilson wrote in 2005, that part of the German second position had been captured and the part leading north to Le Sars had been outflanked. It appeared that German resistance in the centre was crumbling but the 41st Division had suffered many losses, its units were much intermingled and in the confusion a brigade fell back from Flers. Reserve battalions arrived in time to prevent its re-occupation by the Germans but could not advance further. The tanks that had made it onto the battlefield had broken down or been knocked out and German troops were able to conduct several counter-attacks from Gueudecourt. Soon after 4:30 p.m. orders arrived to consolidate. The failure of the attack on the right flank by the XIV Corps divisions, where only the Guards Division reached the first objective, made it impossible for the cavalry to operate and the divisions on the left flank were making a subsidiary attack. The 41st Division and the New Zealand Division had managed swift advances, with the support of some of the tanks that made it onto the battlefield and captured Flers behind a creeping barrage, that showed that tank lanes had been unnecessary.

In 2009, Harris wrote that unlike 1 July, the attack was a big success, High Wood, a 9,000 yd (8,200 m) length of the German first line and 4,000 yd (3,700 m) of the second line being captured, about 6 sq mi (16 km2) or double the amount of 1 July, for about half the casualties. The loss rate was about the same and the divisions were exhausted by the end of the day and needed several days to recover. The tanks had broken down, bogged, got lost or knocked out and in some places, their non-appearance had led to infantry being shot down by German machine-gunners in the un-bombarded tank lanes. In other places the tanks that did reach the German lines were a great help in destroying machine-gun nests. Harris wrote that the same results at a lower cost would have been achieved by resorting to the methodical approach favoured by Rawlinson, even if the tanks had been left out. The capture of the second position may have taken another 24–48 hours but could have left the infantry less depleted and tired, able to attack the third line sooner. The attacks ordered for 16 September were poorly executed and it rained from 17–21 September. French attacks were far less successful and Fayolle wanted to relieve all the divisions in the front line and during the delay, British attacks were limited to local operations, the 6th Division capturing the Quadrilateral on 18 September and it took until 25 September to attack the German third position in the Battle of Morval.

In 2009, Philpott wrote that German historians admitted that the defence almost collapsed on 15 September. The attack was a success because 4,000 yd (3,700 m) of the third position and all of the intermediate line had been captured, although the fastest advance had been on a flank rather than in the centre. Bigger general attacks worked better than smaller local attacks and almost had a strategic effect but this was not realised, the infantry dug in and the cavalry was not called forward. On 16 September, Rawlinson ordered the victory to be followed up before the Germans recovered but the attacking divisions had lost 29,000 casualties and could only manage disjointed local line-straightening attacks. Rainstorms then forced a pause in operations. A faster tempo of attacks had more potential than periodic general attacks interspersed by numerous small attacks, by denying the Germans time to recover. Foch and Fayolle shared the optimism of the British commanders that decisive results were imminent and Below called the German losses on 15 September serious even by Somme standards, many of the German battalions losing 50 percent of their number, depressing the morale of the survivors. The success of the big French attack on 12 September and the British attack on 15 September were followed by an attack on the southern flank by the Tenth Army from 15–18 September. Another rain delay interrupted the sequence but on 26 September, the French and British were able to conduct the biggest combined attack since 1 July.

Philpott wrote that English writing tended to portray the attack as an attempt to pull a weakening and demoralised French army forward and an overoptimistic attempt at a decisive battle by Haig, which was a misunderstanding, the more expansive plans insisted upon by Haig were operational schemes, not tactical directives, for an army which by September, had become capable of emulating the French armies. It was Haig's job to think big, even if all offensives began with trench-to-trench attacks. Looked at in isolation, the September attacks appear to be more of the same, bigger but limited attrition attacks with equally limited results. Studied in context the attacks reflected the new emphasis by Foch on a concerted offensive, given the impossibility of mounting a combined one. The French attacks in September were bigger and more numerous than the British efforts and were part of a deliberate sequence, the Sixth Army on 3, 12, 25 and 26 September, the Tenth Army on 4 and 17 September, the Fourth Army on 15, 25 and 26 September and the Reserve Army on 27 September, which brought the German defence to a crisis. The Anglo-French advanced further and faster in September, inflicting more damage on the defenders but until a faster tempo and better supply was achieved tactical success could not be turned into a strategic victory.

Tanks

In his 1963 biography of Haig, Terraine wrote that after the war Churchill held that the prospect of a great victory by using tanks en masse had been squandered by their premature use to capture "a few ruined villages". Swinton wrote that committing the few tanks available was against the advice of those who had been most involved in their development. Lloyd George wrote that a great secret was wasted on a hamlet not worth capturing. Wilfrid Miles, the official historian, wrote in 1938 that the use of the tanks on 15 September was as mistaken as the German use of gas at the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, wasting the surprises they created. In his 1959 history of the Royal Tank Corps, Liddell Hart called the decision to use the tanks a long-odds gamble by Haig. Terraine wrote that Haig had found out about the experiments with tracked armoured vehicles in 1915 and sent observers to the 1916 trials in England, after which Haig ordered forty tanks, then increased the order to 100. Haig began to consider them as part of the equipment for the battle being planned on the Somme, three months before it commenced. When informed that 150 tanks would be ready by 31 July, he replied that he needed fifty on 1 June and stressed that the tactics of their use must be studied.

Records from GHQ in France, show that as many tanks as possible were going to be used as soon as possible but by 15 September, only 49 were ready and only 18 contributed to the battle. Terraine wrote that using tanks in mid-September was not a gamble and the real question was whether tanks could be used at all in 1916, given the slow rate of production, novelty and the need to train crews. Joffre had pressed for another combined attack as big as 1 July, being anxious about the state of the Russian army and had wanted this earlier than 15 September. Haig was equally doubtful about the fighting power of the French and Russian armies and felt that German peace feelers, captured documents showing increased war-weariness and the destruction of Austro-Hungarian units in the Brusilov Offensive, meant that a German collapse was possible. After suffering 196,000 British and 70,351 French losses on the Somme, against an estimated 200,000 German casualties (actually 243,129) by the end of August, the mid-September attack was the last opportunity for a big combined attack by the French and British armies in 1916. Terraine wrote that it was absurd to think that a possibly decisive weapon would not be used.

Philpott wrote that the début of the tank had been a disappointment, despite their suppression of machine-guns, because of their unreliability, which caused more losses than German counter-fire. Of the fifty tanks in France, 49 were assembled for the attack, 36 reached the front line and 27 reached the German front line but only six reached the third objective. On 16 September, three tanks were operational and such losses showed that the tactics of tank warfare had yet to be developed. The tank would have to remain an accessory to a conventional attack, as part of the furniture of tactical attrition, advancing with infantry in co-operation with artillery, rather than as an independent battle-winning weapon; despite the disappointing results, Haig ordered another 1,000 tanks. The British public was enthusiastic, after reading vastly exaggerated press reports of their feats and in Germany, press reports dwelt on the tanks' vulnerability to armour-piercing bullets and field artillery. Geoffrey Malins, one of the photographers of the film The Battle of the Somme (released on 21 August), titled his new film The Battle of the Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks which went on view in January 1917.

For several weeks after 15 September, the Germans were puzzled about the new weapon, being unable to distinguish between accurate reports of their shape and size and the more fanciful accounts. The existence of male and female tanks apparently led Germans to believe that there were a mass of specialist vehicles and sight of a knocked-out tank north of Flers, caused an officer to conclude that it had a single, wide caterpillar track, which caused much confusion to military intelligence. On 28 September, an intelligence officer included the report along with an accurate description and that much was still uncertain about how the vehicles were built, how many types there were or how big. Bavarian gunners taken prisoner reported that the tanks were a surprise and that the "Spitzgeschoss mit Kern" ( S.m.K. pointed projectile with core) bullets issued earlier had not been intended for anti-tank fire. The tanks that did confront German and Bavarian troops caused panic and prisoners said that it was not war but butchery. Later in the month, a German intelligence officer wrote that only time would tell if the new weapon was of any value.

A month after its début, German troops were still panicking when confronted by the machines but on 28 September, a party of Germans attacked a bogged tank and managed to get on the roof, only to find that there was still no way to fire inside. Rifle-fire was seen to be futile and machine-gun fire appeared only to work only with S.m.K. bullets, when concentrated in one place. It was considered that a hand-grenade would be just as useless but that one with the heads of six more wired around it would have enough explosive power, if thrown against the tracks. Advice was to lie still rather than run and wait for them to go past, to be engaged by artillery of at least 60 mm calibre firing at close range. Passive defences such as road obstacles were suggested but not anti-tank ditches or mines.

By the end of 1916, German interrogators were recording comments by British prisoners, that tanks were only useful in certain circumstances, that it would take time for the new weapon to mature and that the Germans were equally expected to need more time to counter the tank or build their own. On 5 October, the 6th Army sent a report that the British tactic was thought to be to conceal numbers of tanks close to the front line and use them for infantry support. The British had been able to use them only in small numbers and the tanks had advanced with the infantry, halted at the German front line and fired machine-guns into it. Where gaps appeared in the German defence, the tanks had skilfully driven through and attacked the Germans on the flanks from behind, while others had driven deeper into the position to attack command posts and artillery batteries. The British were also reported to have brought up cavalry to exploit larger breaches and that when tanks had been encountered at close range, German infantry had panicked.

In his 2011 biography of Haig, Sheffield wrote that the tanks had been slow and unreliable and were the cause of huge casualties where tank lanes had been left in the barrage. In August after watching a demonstration, Haig had written that army thinking about the tactical use of tanks needed to be clarified. The integration of tanks into the BEF weapons system that was developing was rudimentary and Rawlinson was much less optimistic about their potential. Sheffield criticised the "20/20 hindsight" of writers who complained that using the tanks was premature and agreed with Haig that it was "folly [to fail] to use every means at my disposal in what was likely to be the crowning effort this year". With the tanks in France, their secret would have been revealed before long anyway.

Air Operations

The German official historians wrote that on the Somme, air operations became vastly more important to ground operations and that;

Control of the air over the battlefield had now become imperative for success.

- Der Weltkrieg, Volume XI (1938)

The 2nd Canadian Division recorded that contact patrol aircraft had been the only effective means to find the position of its most advanced troops. German regimental histories contain frequent references to the ubiquity of the RFC, the historian of RIR 211 writing, "swarms of planes are passing over our trenches...." on 7 September and that firing at the aircraft only resulted in their trenches being bombarded,

...even when later on our own planes take to the air to free us from our disagreeable tormentors, the British reconnaissance planes do not allow themselves to be disturbed but strong enemy defensive formations pounce on our airmen who cannot dare to become seriously embroiled with such superior forces. This we had to endure all summer; from early to late enemy planes continuously overhead, watching every movement; work on the trenches as well as all arrivals and departures. Disgusting! Nerve shattering!

- RIR 211 historian

The Fliegertruppen on the Somme had received LFG Roland D.I and Halberstadt D.II fighters early the battle, which were faster and better armed than the obsolete Fokker E.III and inflicted losses on the RFC squadrons equipped with the most inferior aircraft. Lieutenant-Colonel H. Dowding, requested that 60 Squadron, after losing its commander, two flight commanders, three pilots and two observers from 1 July – 3 August, be withdrawn into reserve. The commander of the RFC in France, Hugh Trenchard agreed but sacked Dowding soon after.

RFC casualties increased in mid-September, due to a German reorganisation of air units according to function, Kampfeinsitzer units were combined into seven bigger Jagdstaffeln (Jastas, fighter squadrons) with new and better Albatros D.Is and hand-picked pilots, trained at Valenciennes in new tactics based on the Dicta Boelcke. The first of the new aircraft for Jasta 2 arrived on 16 September. A modest technical superiority and better tactics enabled German aircrew to challenge Anglo-French air supremacy but the more manoeuvrable British fighters, greater numbers and aggressive tactics, preventing the Germans from gaining air superiority.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles "World War", "World War I", and "Battle of Flers–Courcelette", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.