World War I (1914-1918)

Second Battle of Arras

The Battle of Arras (also known as the Second Battle of Arras) was a British offensive on the Western Front during World War I. From 9 April to 16 May 1917, British troops attacked German defences near the French city of Arras on the Western Front. The British achieved the longest advance since trench warfare had begun, surpassing the record set by the French French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. Sixth Army on 1 July 1916. The British

French Third Republic was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire. Sixth Army on 1 July 1916. The British The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. advance slowed in the next few days and the German defence recovered. The battle became a costly stalemate for both sides and by the end of the battle the British Third and First armies had suffered about 160,000 casualties and the German 6th Army 125,000 casualties.

The British Empire, was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. advance slowed in the next few days and the German defence recovered. The battle became a costly stalemate for both sides and by the end of the battle the British Third and First armies had suffered about 160,000 casualties and the German 6th Army 125,000 casualties.

For much of the war, the opposing armies on the Western Front were at a stalemate, with a continuous line of trenches from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border. The Allied objective from early 1915 was to break through the German The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. defences into the open ground beyond and engage the numerically inferior German Army (Westheer) in a war of movement. The British attack at Arras was part of the French Nivelle Offensive, the main part of which was to take place on the Aisne 50 miles (80 km) to the south. The aim of the French offensive was to break through the German defences in forty-eight hours. At Arras the British were to re-capture Vimy Ridge, dominating the plain of Douai to the east, advance towards Cambrai and divert German reserves from the French front.

The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, as well as simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe. defences into the open ground beyond and engage the numerically inferior German Army (Westheer) in a war of movement. The British attack at Arras was part of the French Nivelle Offensive, the main part of which was to take place on the Aisne 50 miles (80 km) to the south. The aim of the French offensive was to break through the German defences in forty-eight hours. At Arras the British were to re-capture Vimy Ridge, dominating the plain of Douai to the east, advance towards Cambrai and divert German reserves from the French front.

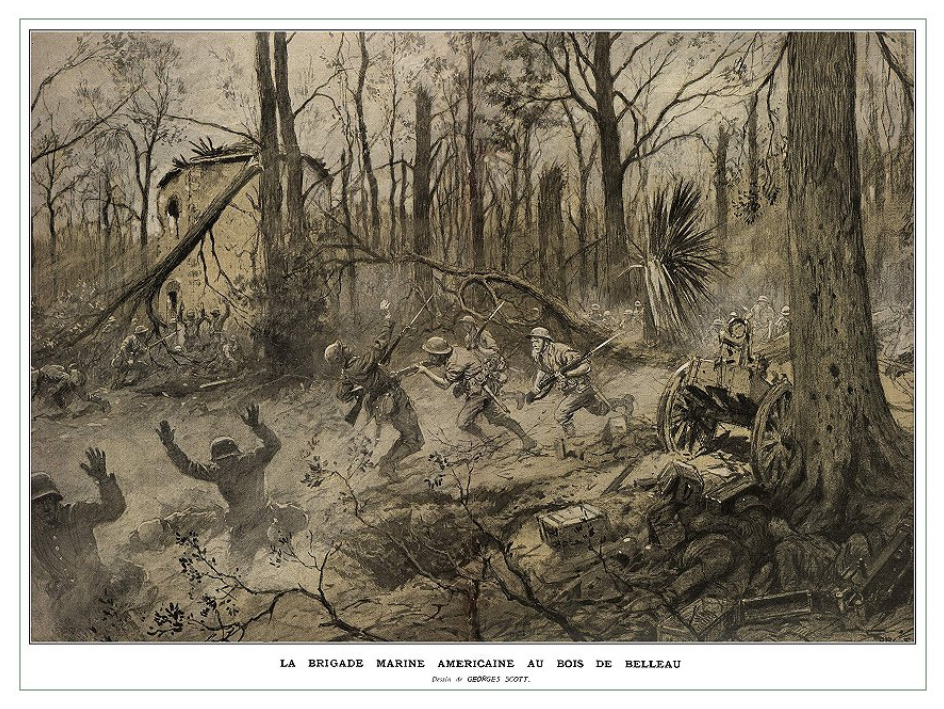

The Battle of Vimy Ridge by Richard Jack

The Battle of Vimy Ridge by Richard Jack (Click image to enlarge)

The British effort was an assault on a relatively broad front between Vimy in the north-west and Bullecourt to the south-east. After a long preparatory bombardment, the Canadian Canada is a country in North America. Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the British North America Act, 1867, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into World War I. Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps, which played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major engagements of the war. Corps of the First Army in the north fought the Battle of Vimy Ridge and took the ridge. The Third Army in the centre advanced astride the Scarpe River and in the south, the Fifth Army attacked the Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung) but was frustrated by the defence in depth and made few gains. The British armies then engaged in a series of small-scale operations to consolidate the new positions. Although these battles were generally successful in achieving limited aims, they were costly successes.

Canada is a country in North America. Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the British North America Act, 1867, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into World War I. Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps, which played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major engagements of the war. Corps of the First Army in the north fought the Battle of Vimy Ridge and took the ridge. The Third Army in the centre advanced astride the Scarpe River and in the south, the Fifth Army attacked the Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung) but was frustrated by the defence in depth and made few gains. The British armies then engaged in a series of small-scale operations to consolidate the new positions. Although these battles were generally successful in achieving limited aims, they were costly successes.

When the battle officially ended on 16 May, British Empire troops had made significant advances but had been unable to achieve a breakthrough. New tactics and the equipment to exploit them had been used, showing that the British had absorbed the lessons of the Battle of the Somme and could mount set-piece attacks against fortified field defences. After the Second Battle of Bullecourt (3–17 May), the Arras sector then returned to the stalemate that typified most of the war on the Western Front, except for attacks on the Hindenburg Line and around Lens, culminating in the Canadian Battle of Hill 70 (15–25 August).

British Preparations

Underground

After the Allied conference at Chantilly, Haig issued instructions for army commanders on 17 November 1916, with a general plan for offensive operations in the spring of 1917. The Chief engineer of the Third Army, Major-General E. R. Kenyon, composed a list of requirements by 19 November, for which he had 16 Army Troops companies, five with each corps in the front line and one with XVIII Corps, four tunnelling companies, three entrenching battalions, eight RE labour battalions and 37 labour companies. Inside the old walls of Arras were the Grand and Petit places, under which there were old cellars, which were emptied and refurbished for the accommodation of 13,000 men. Under the suburbs of St Sauveur and Ronville were many caves, some huge, which were rediscovered by accident in October 1916. When cleared out the caves had room for 11,500 men, one in the Ronville system housing 4,000 men. The 8 ft × 6 ft (2.4 m × 1.8 m) Crinchon sewer followed the ditch of the old fortifications and tunnels were dug from the cellars to the sewer.

Two long tunnels were excavated from the Crinchon sewer, one through the St Sauveur and one through the Ronville system, allowing the 24,500 troops safely sheltered from German bombardment to move forward underground, avoiding the railway station, an obvious target for bombardment. The St Sauveur tunnel followed the line of the road to Cambrai and had five shafts in no man's land but the German retirement to the Hindenburg Line forestalled the use of the Ronville tunnels, when the German front line was withdrawn 1,000 yd (910 m) and there was no time to extend the diggings. The subterranean workings were lit by electricity and supplied by piped water, with gas-proof doors at the entrances; telephone cables, exchanges and testing-points used the tunnels, a hospital was installed and a tram ran from the sewer to the St Sauveur caves. The observation post for the VI Corps heavy artillery off the St Sauveur tunnel, had a telephone exchange with 750 circuits; much of the work in this area being done by the New Zealand Tunnelling Company.

On the First Army front German sappers also conducted underground operations, seeking out Allied tunnels to assault and counter-mine, in which 41 New Zealand tunnellers were killed and 151 wounded. The British tunnellers had gained an advantage over the German miners by the Autumn of 1916, which virtually ended the German underground threat. The British turned to digging 12 subways about 25 ft (7.6 m) down, to the front line, the longest tunnel being 1,883 yd (1.070 mi; 1.722 km) long of the 10,500 yd (6.0 mi; 9.6 km) dug. In one sector, four Tunnelling companies of 500 men each, worked around-the-clock in 18-hour shifts for two months to dig 12 mi (20 km) of subways for foot traffic, tramways with rails for hand-drawn trolleys and a light railway system. Most tunnels were lit by electricity, accommodated telephone cables and some had trams and water supplies. Caverns were dug into the sides for brigade and battalion HQs, first aid posts and store-rooms. The subways were found to be a most efficient way to relieve troops in the line, form up for the attack and then to evacuate wounded. Some of the tunnels were continued into Russian Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. saps with exits in mine craters in no man's land and new mines were laid. Galleries were dug to be opened after the attack for communication or cable trenches, the work being done by the 172nd, 176th, 182nd and 185th Tunnelling companies (Lieutenant-Colonel G. C. Williams, Controller of Mines First Army).

Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. Russia remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire. saps with exits in mine craters in no man's land and new mines were laid. Galleries were dug to be opened after the attack for communication or cable trenches, the work being done by the 172nd, 176th, 182nd and 185th Tunnelling companies (Lieutenant-Colonel G. C. Williams, Controller of Mines First Army).

War in the Air

Although the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) entered the battle with inferior aircraft to the Luftstreitkräfte, this did not deter their commander, General Trenchard, from adopting an offensive posture. Dominance of the air over Arras was essential for reconnaissance and the British carried out many aerial patrols. RFC aircraft carried out artillery spotting, photography of trench systems and bombing. Aerial observation was hazardous work as, for best results, the aircraft had to fly at slow speeds and low altitude over the German defences. It became even more dangerous with the arrival of the Red Baron, Manfred von Richthofen in March 1917. The presence of Jasta 11 led to sharply increased losses of Allied pilots and April 1917, became known as Bloody April. A German infantry officer later wrote,

...during these days, there was a whole series of dogfights, which almost invariably ended in defeat for the British since it was Richthofen's squadron they were up against. Often five or six planes in succession would be chased away or shot down in flames.

- Ernst Jünger

The average flying life of a RFC pilot in Arras in April was 18 hours and from 4–8 April, the RFC lost 75 aircraft and 105 aircrew. The casualties created a pilot shortage and replacements were sent to the front straight from flying school; during the same period, 56 aircraft were crashed by inexperienced RFC pilots.

Artillery

To keep enemy action to a minimum during the assault, a creeping barrage was planned. This required gunners to create a curtain of high explosive and shrapnel shell explosions that crept across the battlefield in lines, about one hundred metres in advance of the assaulting troops. The Allies had previously used creeping barrages at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle and the Battle of the Somme but had encountered two technical problems. The first was accurately synchronising the movement of the troops to the fall of the barrage: for Arras, this was overcome by rehearsal and strict scheduling. The second was the barrage falling erratically as the barrels of heavy guns wore swiftly but at differing rates during fire: for Arras, the rate of wear of each gun barrel was calculated and calibrated accordingly. While there was a risk of friendly fire, the creeping barrage forced the Germans to remain in their shelters, allowing Allied soldiers to advance without fear of machine gun fire. The new instantaneous No. 106 Fuze had been adapted from a French design for high-explosive shells so that they detonated on the slightest impact, vaporising barbed wire. Poison gas shells were used for the final minutes of the barrage.

The principal danger to assaulting troops came from enemy artillery fire as they crossed no man's land, accounting for over half the casualties at the first day of the Somme. A further complication was the location of German artillery, hidden as it was behind the ridges. In response, specialist artillery units were created to attack German artillery. Their targets were provided by 1st Field Survey Company, Royal Engineers, who collated data obtained from flash spotting and sound ranging. (Flash spotting required Royal Flying Corps observers to record the location of telltale flashes made by guns whilst firing.) On Zero-Day, 9 April, over 80 percent of German heavy guns in the sector were neutralised (that is, "unable to bring effective fire to bear, the crews being disabled or driven off") by counter-battery fire. Gas shells were also used against the draught horses of the batteries and to disrupt ammunition supply columns.

Tanks

Forty tanks of the 1st Brigade were to be used in the attack on the Third Army front, eight with XVIII Corps and sixteen each in VII Corps and VI Corps. When the blue line had been reached, four of the VII Corps tanks were to join VI Corps for its attack on the brown line. The black line (first objective) was not to be attacked by tanks, which were to begin the drive to the front line at zero hour and rendezvous with infantry at the black line two hours later. The tanks were reserved for the most difficult objectives beyond the black line in groups of up to ten vehicles. Four tanks were to attack Neuville Vitasse, four against Telegraph Hill, four against The Harp and another four against Tilloy lez Mofflaines and two were to drive down the slope from Roclincourt west of Bois de la Maison Blanche. Once the blue line had fallen, the tanks still running were to drive to rally points.

Aftermath

By the standards of the Western front, the gains of the first two days were nothing short of spectacular. A great deal of ground was gained for relatively few casualties and a number of strategically significant points were captured, notably Vimy Ridge. Additionally, the offensive succeeded in drawing German troops away from the French offensive in the Aisne sector. In many respects, the battle might be deemed a victory for the British and their allies but these gains were offset by high casualties and the ultimate failure of the French offensive at the Aisne. By the end of the offensive, the British had suffered more than 150,000 casualties and gained little ground since the first day. Despite significant early gains, they were unable to break through and the situation reverted to stalemate. Although historians generally consider the battle a British victory, in the wider context of the front, it had very little impact on the strategic or tactical situation. Ludendorff later commented "no doubt exceedingly important strategic objects lay behind the British attack but I have never been able to discover what they were". Ludendorff was also "very depressed; had our principles of defensive tactics proved false and if so, what was to be done?".

Casualties

The most quoted Allied casualty figures are those in the returns made by Lt-Gen Sir George Fowke, Haig's adjutant-general. His figures collate the daily casualty tallies kept by each unit under Haig's command. Third Army casualties were 87,226; First Army 46,826 (including 11,004 Canadians at Vimy Ridge); and Fifth Army 24,608; totalling 158,660. German losses are more difficult to determine. Gruppe Vimy and Gruppe Souchez suffered 79,418 casualties but the figures for Gruppe Arras are incomplete. The writers of the German Official History Der Weltkrieg, recorded 78,000 British losses to the end of April and another 64,000 casualties by the end of May, a total of 142,000 men and 85,000 German casualties. German records excluded those "lightly wounded". Captain Cyril Falls (the writer of the Official History volume on the battle) estimated that 30 percent needed to be added to German returns for comparison with the British. Falls made "a general estimate" that German casualties were "probably fairly equal". Nicholls puts them at 120,000 and Keegan at 130,000.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles "World War", "World War I", and "Second Battle of Arras", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.