Battle of Châlons (451 AD)

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of Châlons or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD between a coalition led by the Roman general Flavius Aetius and the Visigothic king Theodoric I against the Huns and their vassals commanded by their king Attila. It was one of the last major military operations of the Western Roman Empire, although Germanic foederati composed the majority of the coalition army. Whether the battle was strategically conclusive is disputed: The Romans stopped the Huns' attempt to establish vassals in Roman Gaul, and installed Merovech as king of the Franks. However, the Huns successfully looted and pillaged much of Gaul and crippled the military capacity of the Romans and Visigoths. The Hunnic Empire was later dismantled by a coalition of their Germanic vassals at the Battle of Nedao in 454.

Prelude

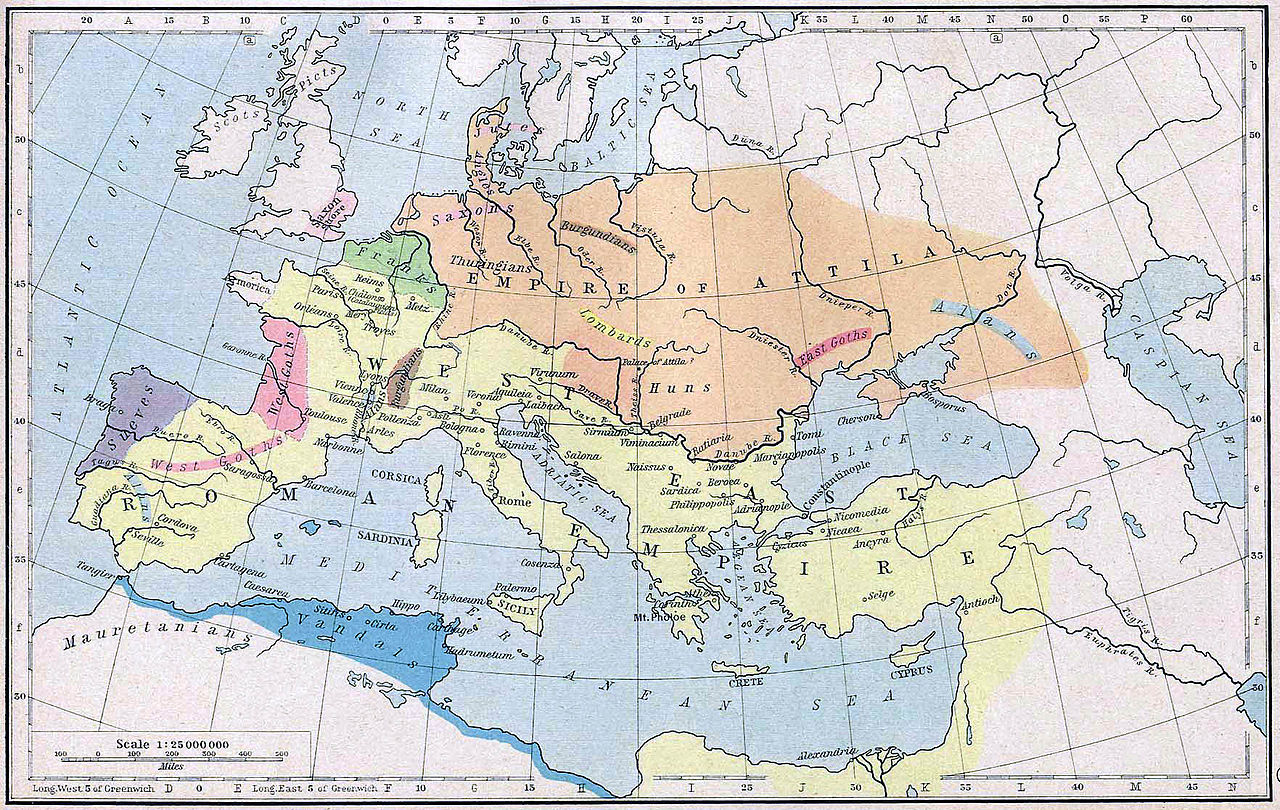

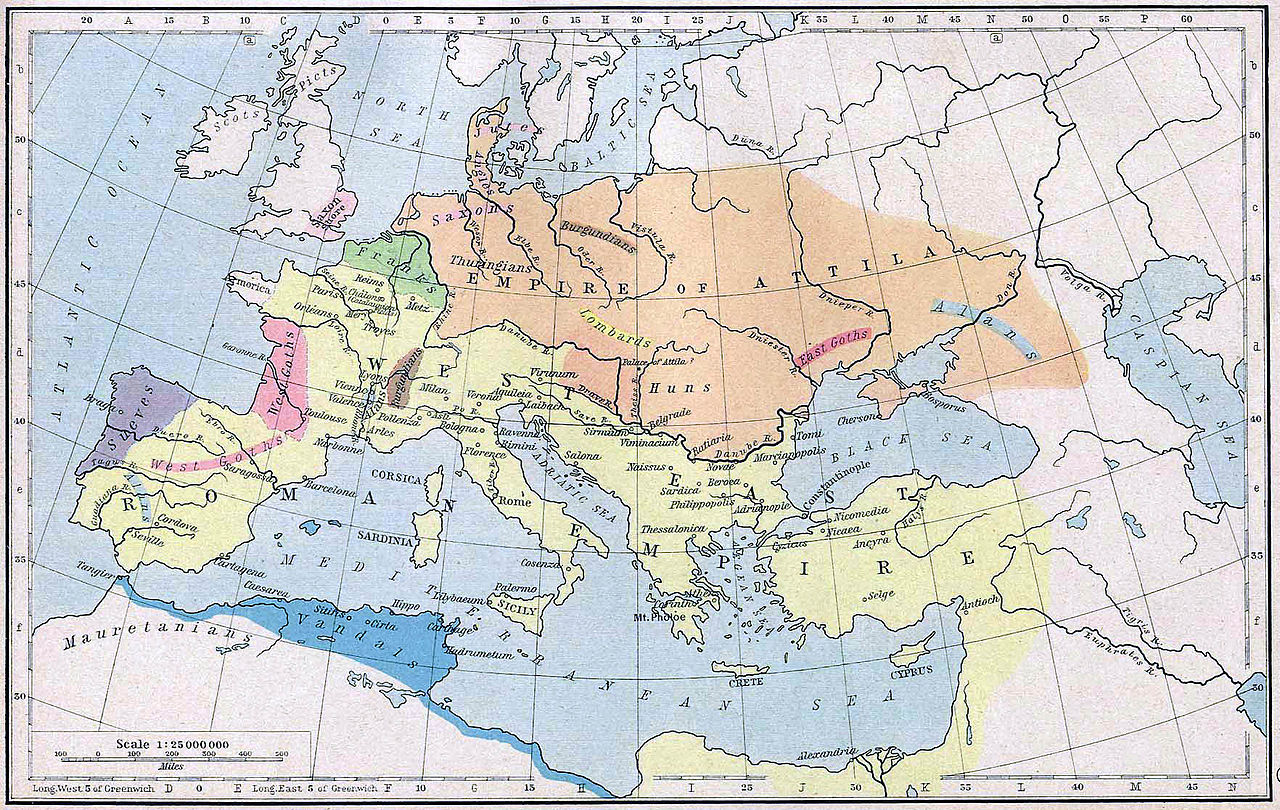

By 450 AD Roman authority over Gaul had been restored in much of the province, although control over all of the provinces beyond Italy was continuing to diminish. Armorica was only nominally part of the empire, and Germanic tribes occupying Roman territory had been forcibly settled and bound by treaty as Foederati under their own leaders. Northern Gaul between the Rhine north of Xanten and the Leie river (Germania Secunda) had unofficially been abandoned to the Salian Franks. The Visigoths on the River Garonne were growing restive, but still holding to their treaty. The Burgundians in Sapaudia were more submissive, but likewise awaiting an opening for revolt. The Alans on the Loire and in Valentinois were more loyal, having served the Romans since the defeat of Jovinus in 411 and the siege of Bazas in 414. The parts of Gaul still securely in Roman control were the Mediterranean coastline; a region including Aurelianum (present-day Orléans) along the Seine and the Loire as far north as Soissons and Arras; the middle and upper Rhine to Cologne; and downstream along the Rhône River.

Roman Empire (yellow) and Hunnic Empire (orange) 450

Roman Empire (yellow) and Hunnic Empire (orange) 450

( Click image to enlarge)

The historian Jordanes states that Attila was enticed by the Vandal king Gaiseric to wage war on the Visigoths. At the same time, Gaiseric would attempt to sow strife between the Visigoths and the Western Roman Empire. However, Jordanes' account of Gothic history is notoriously biased and unreliable, and much of it is omitted or garbled. Other contemporary writers offer different motivations: Honoria, the sister of the emperor Valentinian III, had been betrothed to the former consul Herculanus the year before. In 450, she sent the eunuch Hyacinthus to the Hunnic king asking for Attila's help in escaping her confinement, with her ring as proof of the letter's legitimacy. Allegedly Attila interpreted it as offering her hand in marriage, and he had claimed half of the empire as a dowry. He demanded Honoria to be delivered along with the dowry. Valentinian rejected these demands, and Attila used it as an excuse to launch a destructive campaign through Gaul. Hughes suggests otherwise, saying that the reality of this interpretation should be that Honoria was using Attila's status as honorary Magister Militum for political leverage.

Another possible explanation is that in 449, the King of the Franks, Chlodio, died. Aetius had adopted the younger son of the Franks to secure the Rhine Frontier, and the elder son had fled to the court of Attila. Bona and more recently Kim take this theory a step further, reasoning that it was the real cause of the war, and the primary reason Attila attacked Gaul. Bona argues that Childeric was a vassal of Attila, and he identifies the founders of the Merovingian dynasty as the two claimants to the Frankish throne. In the somewhat garbled story of the Chronicle of Fredregar, Childeric was expelled by the Franks and allegedly forced to live in exile in Thuringia for eight years, which was a Hunnic vassal at the time. Kim argues that the character of Wiomad represents the Huns who helped Childeric fight the Romans and engineered his return from exile, and concludes that the main objective of Attila at Chalons was conquest of the Franks and establishment of vassal states on the Rhine.

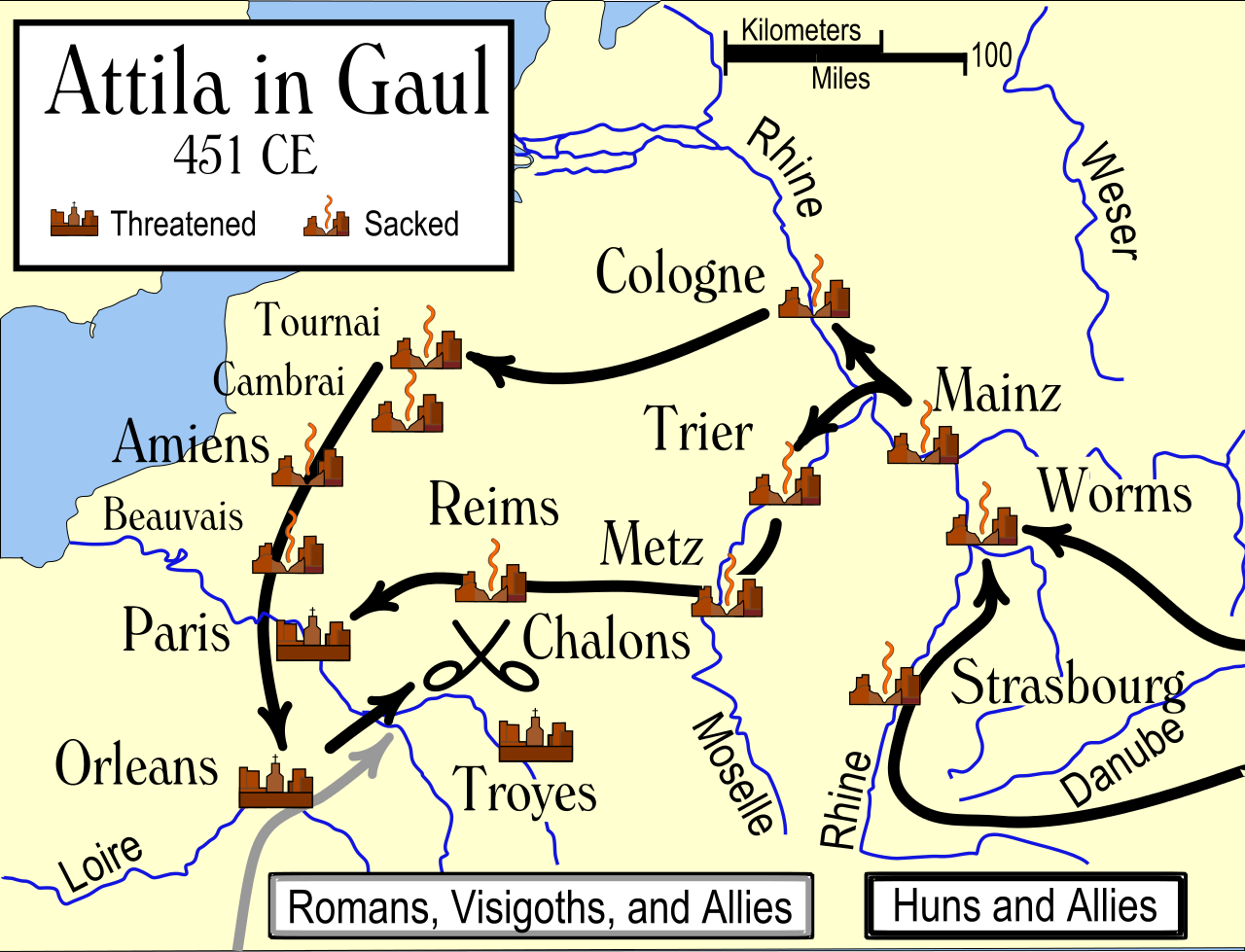

The map shows the possible routes taken by Attila's forces as they invaded Gaul, and the major cities that were sacked or threatened by the Huns and their allies

Attila crossed the Rhine early in 451 with his followers and a large number of allies, sacking Divodurum (Metz) on April 7. Other cities attacked can be determined by the hagiographic vitae written to commemorate their bishops: Nicasius was slaughtered before the altar of his church in Rheims; Saint Servatius is alleged to have saved Tongeren with his prayers, as Genevieve is to have saved Paris. Lupus, bishop of Troyes, is also credited with saving his city by meeting Attila in person. Many other cities also claim to have been attacked in these accounts, although archaeological evidence shows no destruction layer dating to the timeframe of the invasion. The most likely explanation for Attila's widespread devastation of Gaul is that Attila's main column crossed the Rhine at Worms or Mainz and then marched to Trier, Metz, Reims, and finally Orleans, while sending a small detachment north into Frankish territory to plunder the countryside. This explanation would support the literary evidence claiming North Gaul was attacked, and the archaeological evidence showing major population centers were not sacked.

Attila's army had reached Aurelianum (modern Orleans, France France, officially the French Republic is transcontinental country predominantly located in Western Europe and spanning overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. France reached its political and military zenith in the early 19th century under Napoleon Bonaparte, subjugating much of continental Europe and establishing the First French Empire.) before June. According to Jordanes, the Alan king Sangiban, whose Foederati realm included Aurelianum, had promised to open the city gates. This siege is confirmed by the account of the Vita S. Aniani and in the later account of Gregory of Tours, although Sangiban's name does not appear in their accounts. However, the inhabitants of Aurelianum shut their gates against the advancing invaders, and Attila began to besiege the city, while he waited for Sangiban to deliver on his promise. There are two different accounts of the siege of Aurelianum, and Hughes suggests that combining them provides a better understanding of what actually happened. After four days of heavy rain, Attila began his final assault on June 14, which was broken due to the approach of the Roman coalition. Modern scholars tend to agree that the siege of Aurelianum was the high point of Attila's attack on the West, and the staunch Alan defence of the city was the real decisive factor in the war of 451. Contrary to Jordanes, the Alans were never planning to defect as they were the loyal backbone of the Roman defence in Gaul.

France, officially the French Republic is transcontinental country predominantly located in Western Europe and spanning overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. France reached its political and military zenith in the early 19th century under Napoleon Bonaparte, subjugating much of continental Europe and establishing the First French Empire.) before June. According to Jordanes, the Alan king Sangiban, whose Foederati realm included Aurelianum, had promised to open the city gates. This siege is confirmed by the account of the Vita S. Aniani and in the later account of Gregory of Tours, although Sangiban's name does not appear in their accounts. However, the inhabitants of Aurelianum shut their gates against the advancing invaders, and Attila began to besiege the city, while he waited for Sangiban to deliver on his promise. There are two different accounts of the siege of Aurelianum, and Hughes suggests that combining them provides a better understanding of what actually happened. After four days of heavy rain, Attila began his final assault on June 14, which was broken due to the approach of the Roman coalition. Modern scholars tend to agree that the siege of Aurelianum was the high point of Attila's attack on the West, and the staunch Alan defence of the city was the real decisive factor in the war of 451. Contrary to Jordanes, the Alans were never planning to defect as they were the loyal backbone of the Roman defence in Gaul.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Battle of the Catalaunian Plains", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.