Battle of Hastings (1066)

Harold Moves South

After defeating his brother Tostig and Harald Hardrada in the north, Harold left much of his forces in the north, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest of his army south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion. It is unclear when Harold learned of William's landing, but it was probably while he was travelling south. Harold stopped in London, and was there for about a week before Hastings, so it is likely that he spent about a week on his march south, averaging about 27 miles (43 kilometres) per day, for the approximately 200 miles (320 kilometres). Harold camped at Caldbec Hill on the night of 13 October, near what was described as a "hoar-apple tree". This location was about 8 miles (13 kilometres) from William's castle at Hastings. Some of the early contemporary French accounts mention an emissary or emissaries sent by Harold to William, which is likely. Nothing came of these efforts.

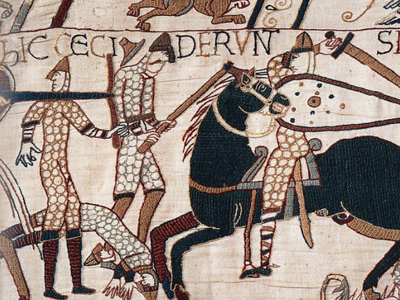

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry depicting mounted Norman soldiers attacking Anglo-Saxons who are fighting on foot in a shield wall

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry depicting mounted Norman soldiers attacking Anglo-Saxons who are fighting on foot in a shield wall

( Click image to enlarge)

Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William's scouts reported the English The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from about 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. The Viking invasions of the 9th century upset the balance of power between the English kingdoms, and native Anglo-Saxon life in general. The English lands were unified in the 10th century in a reconquest completed by King Æthelstan in 927. arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy. Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 miles (9.7 kilometres) from William's castle at Hastings.

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from about 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. The Viking invasions of the 9th century upset the balance of power between the English kingdoms, and native Anglo-Saxon life in general. The English lands were unified in the 10th century in a reconquest completed by King Æthelstan in 927. arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy. Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 miles (9.7 kilometres) from William's castle at Hastings.

English Forces at Hastings

The exact number of soldiers in Harold's army is unknown. The contemporary records do not give reliable figures; some Norman sources give 400,000 to 1,200,000 men on Harold's side. The English sources generally give very low figures for Harold's army, perhaps to make the English defeat seem less devastating. Recent historians have suggested figures of between 5,000 and 13,000 for Harold's army at Hastings, and most modern historians argue for a figure of 7,000–8,000 English troops. These men would have been a mix of the fyrd and housecarls. Few individual Englishmen are known to have been at Hastings; about 20 named individuals can reasonably be assumed to have fought with Harold at Hastings, including Harold's brothers Gyrth and Leofwine and two other relatives.

The English army consisted entirely of infantry. It is possible that some of the higher class members of the army rode to battle, but when battle was joined they dismounted to fight on foot. The core of the army was made up of housecarls, full-time professional soldiers. Their armour consisted of a conical helmet, a mail hauberk, and a shield, which might be either kite-shaped or round. Most housecarls fought with the two-handed Danish battleaxe, but they could also carry a sword. The rest of the army was made up of levies from the fyrd, also infantry but more lightly armoured and not professionals. Most of the infantry would have formed part of the shield wall, in which all the men in the front ranks locked their shields together. Behind them would have been axemen and men with javelins as well as archers.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Battle of Hastings", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.