First Messenian War (743—724 BC)

Course

The Capture of Ampheia for use as a Spartan Base

Despairing finally of remedies at law for the murders of their citizens the Spartans resolved to go to war without the usual heraldic notification or any other warning to the Messenians. Alcmenes assembled an army. When it was ready they swore an oath not to stop fighting until they had taken Messenia no matter whether the war was long or short and regardless of the casualties and cost.

The war's first battle was the Spartan attack on Ampheia, a city of unknown location now, but probably on the western flank of Taygetus. A swift night march brought them to the gates, which stood open. There was no garrison, nor were they in any way expected. The first sign the Ampheians had of war was the Spartans rousing people out of bed to kill them. Some few took refuge in the temples; others fled for their lives. The Spartans sacked the city then turned it into a garrison for the conduct of further operations against Messenia. The Messenian women and children were captured. The men who had survived the massacre were sold into slavery.

When the news of Ampheia spread a crowd gathered at the capital, Stenykleros ("rough acres," location unknown, perhaps under Messene), from all of Messenia. They were addressed by the king, Euphaes. He encouraged them to be true men in the hour of need, assuring them that justice and the gods were on their side because they had not attacked first. Subsequently he placed the entire citizenry under arms and arranged for their training.

From the beginning Euphaes relied on fixed defenses. He fortified and garrisoned the towns but avoided forays against the Spartan army. For two seasons more the Spartans raided the moveable wealth, especially confiscating grain and money, but were ordered to spare capital equipment such as buildings and trees, which might be of use after the war. In this matrix of fortified points the Spartans could never successfully siege any one point. Declining to attack the main Spartan army, the Messenians could only assault undefended Spartan border communities when the opportunity arose.

The Skirmish for the Fortified Camp on the Ravine

In the fourth campaigning season; that is, in the summer of 739 according to Pausanias' dating scheme, Euphaes resolved to bring the war to the Spartans at Ampheia ("let loose the full blast of Messenian anger"). The Spartans were denying the Messenians use of the countryside for agriculture. Subsequent events show that this denial was untenable in the long term for the Messenians. They needed to strike a blow to remove the Spartan presence from their country.

Euphaes judged that his army was sufficiently trained to oppose the Spartan professional soldiers. He readied an expedition and subsequently marched out of the capital in what must have been the direction of Ampheia. That his first concern was to construct a fortified base nearer to Ampheia is indicated by the transport of "timber and all the materials for stockades" in his baggage train. No mention is made of any intelligence on the current position of the Spartan army. His actions were not those of a general expecting a battle that day. His intent must have been to move the start line of future attacks closer to the enemy, a standard tactic later used by the Roman army with repeated success.

The Spartans on the other hand were tracking his every movement. They sent immediately for reinforcements from Sparta, who marched directly for the enemy, encountering the Messenians in the middle between Ithome and Taygetus. Their approach was no surprise to Euphaes. Choosing his ground carefully he selected a site with one side bordering an impassable ravine between the Messenians and the Spartans. Nino Luraghi finds it "rather odd" that Euphaes stationed his army where it could not be attacked by the Spartans. Whether he questions the account or the general is not stated, but seen from a different view, the problem disappears.

Subsequent events demonstrate that Euphaes intended to build a fortified camp, which is what he did. The main goal of siting such a camp is to deny the enemy access to it. The Spartan commanders understood Euphaes very well. They sent a force upstream to cross the ravine and outflank the Messenians, preventing them from building a camp, but Euphaes had anticipated this move. Following the Spartans along the other side of the ravine with 500 cavalry and light infantry under Pytharatos and Antandros they prevented the Spartans from crossing. The camp was finished the next day.

The location of the ravine remains unknown nor does the battle have a name. Blocked, the Spartan army withdrew from Messenia. As it did not settle the war the battle is most often called inconclusive. As far as the tactical goals of the two armies are concerned, it was a Messenian victory.

The Pitched Battle in the Vicinity of Ampheia

Both sides knew that in the next campaigning season a major battle would be fought. Meanwhile, at Sparta Alcmenes died and was replaced by his son, Polydorus. Cleonnis commanded the Messenian fortified camp. At the start of the season he took his command to the east to engage a Spartan army that was marching west from Sparta.

Disposition of Troops

They met on the plains beneath Taygetus at a still unknown location in Messenia, perhaps near Ampheia. The battle was mainly a heavy infantry engagement. The terms "light infantry" and "infantry" are being used by Pausanias. The Spartan army was mainly infantry. Some "light infantry" were present as Dryopians, an ethnic group of Pelasgians whose ancestors had been driven from Dryopia by the Dorians, who then called it Doris, and from their Achaean place of refuge, Asine, when Dorian Argos subjected it. They were finally offered protection by Dorian Sparta. These were drafted by the Spartans. Also present was a contingent of Cretan archers. Light troops played little part in the battle; they were mainly spectators.

The two armies faced each other in traditional start lines. Euphaes yielded the command of the Messenian center to Cleonnis, while he took the left flank with Antandros, and Pythartos on the right. Facing Cleonnis was Euryleon, a noble Spartan and a Cadmid, with Polydorus on his left and Theopompus on the right. The latter in his harangue appealed to glory, wealth and the oath they had all taken. Euphaes chose to present death or slavery, pointing to the fate of Ampheia. The signal was given to advance simultaneously on both sides.

The Problem of the Phalanx

Pausanias' description of the battle creates an apparent historical paradox. He refers to "the special characters of the two forces in their behaviors and in their frame of mind." The Messenians "ran charging at the Lakonians reckless of their lives ...." "Some of them leapt forward out of rank and did glorious deeds of courage." The Spartans on the other hand were "careful not to break rank." Says Pausanias, "... knowledge of war was something they had been brought up to, they kept a deeper formation, expecting the Messenians not to hold a line against them for as long as their own would hold ...."

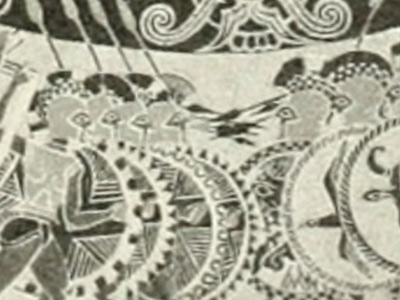

The Spartan tactic being described is that of the phalanx, the unbroken line of men creating a killing zone in front of them. The chief weapon of the ancient Greek phalanx was the spear, which among Macedonian troops reached prodigious lengths. Pausanias says that those who tried to plunder the dead "were speared and stabbed while they were too busy to see what was coming,...."

The paradox is that there is no supporting evidence of the use of the phalanx in Greece at that time. Anthony Snodgrass defined "the hoplite revolution," which included both the use of the phalanx in Greece and standardization of a "hoplite panoply" of arms and equipment. The panoply consisted of artifacts adapted from previous models: corselet, greaves, ankle guards, closed "Corinthian" helmet, large round shield with a band for the arm and a side grip, spear, long steel sword. Each element except the greaves is dated to 750-700 BC, perhaps earlier.

They are first depicted together on Proto-Corinthian vases of 675 BC for the panoply and the phalanx around 650 BC, much too late for either the Great Rhetra or the First Messenian War. Snodgrass dates the small figures of hoplites found in Sparta, "a sign of a unified and self-conscious hoplite class," as he believes, to not before 650. He then questions the date of the Great Rhetra, implying it should be reinterpreted or moved to the 7th century.

After Snodgrass published his analysis of pottery decoration there was a double effort to bring the Great Rhetra to a later time and find phalanxes in an earlier time, neither successful. The earliest evidence that John Salmon found was the vase paintings of the Macmillan Painter, who painted what appear to be phalanxes around the shoulders of Proto-Corinthian aryballoi. The Chigi Vase, for example, shows the overlapping shields, the spears, the grips of the shields and the corselets and closed helmets. It is dated 650; another, the Macmillan aryballos, to 655. The earliest of the series is an aryballos from Perchora dated 675, showing matched pairs, which are not necessarily phalanxes, but they fight in the presence of a flautist. These musicians were specific to phalanxes. They coordinated its movements.

The only supporting evidence for the phalanx therefore is dated to the time of the Second Messenian War, not the First. However, this is proof from a deficit. The vases may only demonstrate that depictions of phalanx warfare began at that time, not that phalanxes did. Pausanias on the other hand is positive evidence. Moreover, attempts to discount or select out what he says often create other problems. He is a vital part of all the evidence for the period.

Establishment of a Fixed Defense at Mt. Ithome

Not wanting to experience another such battle, the Messenians fell back to the heavily fortified Mount Ithome. This is when the Messenians first sent for help from the Oracle at Delphi. They were told that a sacrifice of a royal virgin was the key to their success and the daughter of Aristodemus, a Messenian hero, was chosen for the sacrifice.

Upon hearing of this, the Spartans held off from attacking Ithome for several years, before finally making a long march under their kings and killing the Messenian leader. Aristodemus was made the new Messenian king and led an offensive, meeting the enemy and driving them back into their own territory.

The Fall of Ithome

The Spartans then sent an envoy to Delphi and their following of her advice caused Messenian reverses so great that Aristodemus committed suicide and Ithome fell. The Messenians who had fortified themselves on the mountain either fled abroad or were captured and enslaved.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "First Messenian War (743—724 BC)", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.