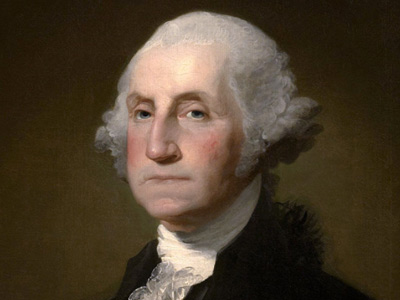

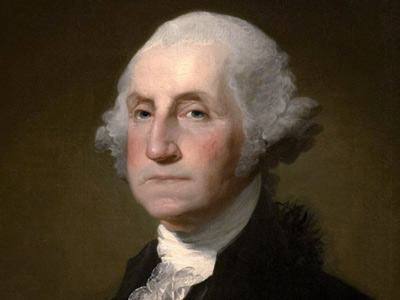

George Washington (1732-1799)

French and Indian War

Washington began his military service in the French and Indian War as a major in the militia of the British Province of Virginia. In 1753, he was sent as an ambassador from the British crown to the French officials and Indians as far north as present-day Erie, Pennsylvania. The Ohio Company was an important vehicle through which British investors planned to expand into the Ohio Valley, opening new settlements and trading posts for the Indian trade. In 1753, the French The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe since the High Middle Ages. It was also an early colonial power, with possessions around the world. Colonial conflicts with Great Britain led to the loss of much of its North American holdings by 1763. The Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic. themselves began expanding their military control into the Ohio Country, a territory already claimed by the British colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania. These competing claims led to a war in the colonies called the French and Indian War (1754–62) and contributed to the start of the global Seven Years' War (1756–63). By chance, Washington became involved in its beginning.

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe since the High Middle Ages. It was also an early colonial power, with possessions around the world. Colonial conflicts with Great Britain led to the loss of much of its North American holdings by 1763. The Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic. themselves began expanding their military control into the Ohio Country, a territory already claimed by the British colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania. These competing claims led to a war in the colonies called the French and Indian War (1754–62) and contributed to the start of the global Seven Years' War (1756–63). By chance, Washington became involved in its beginning.

Beginnings of War

Deputy governor of colonial Virginia Robert Dinwiddie was ordered by the British The Kingdom of Great Britain was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the kingdoms of England (which included Wales) and Scotland to form a single kingdom encompassing the whole island of Great Britain and its outlying islands, with the exception of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. government to guard the British territorial claims, including the Ohio River basin. In late 1753, Dinwiddie ordered Washington to deliver a letter asking the French to vacate the Ohio Valley; he was eager to prove himself as the new adjutant general of the militia, appointed by the Lieutenant Governor himself only a year before. During his trip, Washington met with Tanacharison (also called "Half-King") and other Iroquois chiefs allied with England at Logstown to secure their support in case of a military conflict with the French. He delivered the letter to local French commander Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, who politely refused to leave. Washington kept a diary during his expedition which was printed by William Hunter on Dinwiddie's order and which made Washington's name recognizable in Virginia. This increased popularity helped him to obtain a commission to raise a company of 100 men and start his military career.

The Kingdom of Great Britain was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the kingdoms of England (which included Wales) and Scotland to form a single kingdom encompassing the whole island of Great Britain and its outlying islands, with the exception of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. government to guard the British territorial claims, including the Ohio River basin. In late 1753, Dinwiddie ordered Washington to deliver a letter asking the French to vacate the Ohio Valley; he was eager to prove himself as the new adjutant general of the militia, appointed by the Lieutenant Governor himself only a year before. During his trip, Washington met with Tanacharison (also called "Half-King") and other Iroquois chiefs allied with England at Logstown to secure their support in case of a military conflict with the French. He delivered the letter to local French commander Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, who politely refused to leave. Washington kept a diary during his expedition which was printed by William Hunter on Dinwiddie's order and which made Washington's name recognizable in Virginia. This increased popularity helped him to obtain a commission to raise a company of 100 men and start his military career.

Dinwiddie sent Washington back to the Ohio Country to safeguard an Ohio Company's construction of a fort at present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Before he reached the area, a French force drove out colonial traders and began construction of Fort Duquesne. A small detachment of French troops led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville was discovered by Tanacharison and a few warriors east of present-day Uniontown, Pennsylvania. On May 28, 1754, Washington and some of his militia unit, aided by their Mingo allies, ambushed the French in what has come to be called the Battle of Jumonville Glen. Exactly what happened during and after the battle is a matter of contention, but several primary accounts agree that the battle lasted about 15 minutes, that Jumonville was killed, and that most of his party were either killed or taken prisoner. It is not completely clear whether Jumonville died at the hands of Tanacharison in cold blood, or was somehow shot by an onlooker with a musket as he sat with Washington, or by another means. Following the battle, Washington was given the epithet Town Destroyer by Tanacharison.

The French responded by attacking and capturing Washington at Fort Necessity in July 1754. They allowed him to return with his troops to Virginia. Historian Joseph Ellis concludes that the episode demonstrated Washington's bravery, initiative, inexperience, and impetuosity. Upon his return to Virginia, Washington refused to accept a demotion to the rank of captain, and resigned his commission. Washington's expedition into the Ohio Country had international consequences; the French accused Washington of assassinating Jumonville, who they claimed was on a diplomatic mission. Both France and Great Britain were ready to fight for control of the region and both sent troops to North America in 1755; war was formally declared in 1756.

Braddock Disaster 1755

In 1755, Washington became the senior American aide to British General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Braddock expedition. This was the largest British expedition to the colonies, and was intended to expel the French from the Ohio Country; the first objective was the capture of Fort Duquesne. Washington initially sought an appointment as a major from Braddock, but he agreed to serve as a staff volunteer upon advice that no rank above captain could be given except by London. During the passage of the expedition, Washington fell ill with severe headaches and fever; nevertheless, he recommended to Braddock that the army be split into two divisions when the pace of the troops continued to slow: a primary and more lightly equipped "flying column" offensive which could move at a more rapid pace, to be followed by a more heavily armed reinforcing division. Braddock accepted the recommendation (likely made in a council of war including other officers) and took command of the lead division.

In the Battle of the Monongahela, the French and their Indian allies ambushed Braddock's reduced forces and the general was mortally wounded. After suffering devastating casualties, the British panicked and retreated in disarray. Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnants of the British and Virginian forces into an organized retreat. In the process, he demonstrated bravery and stamina, despite his lingering illness. He had two horses shot from underneath him, while his hat and coat were pierced by several bullets. Two-thirds of the British force of 976 men were killed or wounded in the battle. Washington's conduct in the battle redeemed his reputation among many who had criticized his command in the Battle of Fort Necessity.

Washington was not included by the succeeding commander Col. Thomas Dunbar in planning subsequent force movements, whatever responsibility rested on him for the defeat as a result of his recommendation to Braddock.

Commander of Virginia Regiment

Lt. Governor Dinwiddie rewarded Washington in 1755 with a commission as "Colonel of the Virginia Regiment and Commander in Chief of all forces now raised in the defense of His Majesty's Colony" and gave him the task of defending Virginia's frontier. The Virginia Regiment was the first full-time American military unit in the colonies, as opposed to part-time militias and the British regular units. He was ordered to "act defensively or offensively" as he thought best. He happily accepted the commission, but the coveted red coat of officer rank (and the accompanying pay) continued to elude him. Dinwiddie as well pressed in vain for the British military to incorporate the Virginia Regiment into its ranks.

In command of a thousand soldiers, Washington was a disciplinarian who emphasized training. He led his men in brutal campaigns against the Indians in the west; his regiment fought 20 battles in 10 months and lost a third of its men. Washington's strenuous efforts meant that Virginia's frontier population suffered less than that of other colonies; Ellis concludes that "it was his only unqualified success" in that war.

In 1758, Washington participated in the Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. He was embarrassed by a friendly fire episode in which his unit and another British unit each thought that the other was the French enemy and opened fire, with 14 dead and 26 wounded in the mishap. Washington was not involved in any other major fighting on the expedition, and the British scored a major strategic victory, gaining control of the Ohio Valley when the French abandoned the fort. Following the expedition, he retired from his Virginia Regiment commission in December 1758. He did not return to military life until the outbreak of the revolution in 1775.

Lessons Learned

Washington never gained the commission in the British army that he yearned for, but in these years he gained valuable military, political, and leadership skills. He closely observed British military tactics, gaining a keen insight into their strengths and weaknesses that proved invaluable during the Revolution. Washington learned to organize, train, drill, and discipline his companies and regiments. He learned the basics of battlefield tactics from his observations, readings, and conversations with professional officers, as well as a good understanding of problems of organization and logistics. He gained an understanding of overall strategy, especially in locating strategic geographical points.

Washington demonstrated his resourcefulness and courage in the most difficult situations, including disasters and retreats. He developed a command presence, given his size, strength, stamina, and bravery in battle, which demonstrated to soldiers that he was a natural leader whom they could follow without question. Washington's fortitude in his early years was sometimes manifested in less constructive ways. Biographer John R. Alden contends that Washington offered "fulsome and insincere flattery to British generals in vain attempts to win great favor" and on occasion showed youthful arrogance, as well as jealousy and ingratitude in the midst of impatience.

Historian Ron Chernow is of the opinion that his frustrations in dealing with government officials during this conflict led him to advocate the advantages of a strong national government and a vigorous executive agency that could get results; other historians tend to ascribe Washington's position on government to his later American Revolutionary War service. He developed a very negative idea of the value of militia, who seemed too unreliable, too undisciplined, and too short-term compared to regulars. On the other hand, his experience was limited to command of at most 1,000 men and came only in remote frontier conditions that were far removed from the urban situations that he faced during the Revolution at Boston, New York, Trenton, and Philadelphia.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "George Washington (1732-1799)", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.