Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC)

Battle of Heraclea (280 BC) and Subsequent Negotiations

Publius Valerius Laevinus, one of the two consuls for 280 BC, was marching against Pyrrhus with a large army and plundering Lucania on his way. He wanted to fight as far away from Roman territory as possible and hoped that by marching on Pyrrhus he would frighten him. He seized a strong strategic point in Lucania to hinder those who wanted to aid Pyrrhus. Pyrrhus sent him a letter saying that he had come to the aid of the Tarentines and the Italic peoples and asking the Romans to leave him to settle their differences with the Tarentines, Lucanians and Samnites. He would arbitrate justly and redress any damage these peoples may have caused. He called on the Romans to offer sureties with respect to any charges against them and abide by his decisions. If Romans The Roman Republic was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establishment of the Roman Empire, Rome's control rapidly expanded during this period - from the city's immediate surroundings to hegemony over the entire Mediterranean world. accepted this he would be their friend; if they did not, it would be war.

The Roman Republic was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establishment of the Roman Empire, Rome's control rapidly expanded during this period - from the city's immediate surroundings to hegemony over the entire Mediterranean world. accepted this he would be their friend; if they did not, it would be war.

The consul replied the Romans would not accept him as a judge for their disputes with other peoples. They did not fear him as a foe, and would fight and exact penalties they wished. Pyrrhus should think who he would offer as sureties for the payment of penalties. He also invited Pyrrhus to put his issues before the senate. Laevinus captured some scouts and showed them his troops, telling them that he had many more men, and sent them back to Pyrrhus.

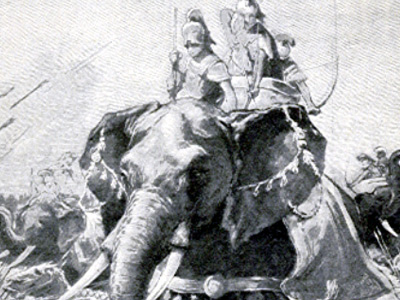

Pyrrhus had not yet been joined by his allies and took to the field with his forces. He set up his camp on the plain between the cities of Pandosia and Heracleia. He then went to see the Roman camp further along the River Siris. He decided to delay to wait for his allies and, hoping that the supplies of the Romans, who were in hostile territory, would fail, placed guards by the river. The Romans decided to move before his allies would arrive and forded the river. The guards withdrew. Pyrrhus, now worried, placed the infantry in battle line and advanced with the cavalry, hoping to catch the Romans while they were still crossing. Seeing the large Roman infantry and cavalry advancing towards him, Pyrrhus formed a close formation and attacked. The Roman cavalry began to give way and Pyrrhus called in his infantry. The battle remained undecided for a long time. The Romans were pushed back by the elephants and their horses were frightened of them. Pyrrhus then deployed the Thessalian cavalry. The Romans were thrown into confusion and were routed.

Zonaras wrote that all the Romans would have been killed had it not been for a wounded elephant trumpeting and throwing the rest of these animals into confusion. This "restrained Pyrrhus from pursuit and the Romans thus managed to cross the river and make their escape into an Apulian city." Cassius Dio wrote that "Pyrrhus became famous for his victory and acquired a great reputation from it, to such an extent that many who had been remaining neutral came over to his side and all the allies who had been watching the turn of events joined him. He did not openly display anger towards them nor did he entirely conceal his suspicions; he rebuked them somewhat for their delay, but otherwise received them kindly." Plutarch noted that Dionysius of Halicarnassus stated that nearly 15,000 Romans and 13,000 Greeks fell, but according to Hieronymus of Cardia 7,000 Romans and 4,000 Greeks fell. The text of Hieronymus of Cardia has been lost and the part of the text of Dionysius which mentions this is also lost. Plutarch wrote that Pyrrhus lost his best troops and his most trusted generals and friends. However, some of cities allied with the Romans went over to him. He marched to within, 60 kilometres from Rome, plundering the territories along the way. He was joined belatedly by many of the Lucanians and Samnites. Pyrrhus was glad that he had defeated the Romans with his own troops.

Cassius Dio wrote that Pyrrhus learnt that Gaius Fabricius Luscinus and other envoys were approaching to negotiate about his captives. He sent a guard for them as far as the border and then went to meet them. He escorted them into the city and entertained and honoured them, hoping for a truce. Fabricius said he had come to get back their captives and Pyrrhus was surprised they had not been commissioned to negotiate peace terms. Pyrrhus said that he wanted to make friends and a peace treaty and that he would release the prisoners without a ransom. The envoys refused to negotiate such terms. Pyrrhus handed over the prisoners and sent Cineas to Rome with them to negotiate with the Roman senate. Cineas lingered before seeking an audience with the senate to visit the leading men of Rome. He went to the senate after he had won over many of them. He offered friendship and an alliance. There was a long debate in the senate and many senators were inclined to make a truce.

Livy and Justin, like Cassius Dio, placed Gaius Fabricius and the other envoys going to see Pyrrhus before Cineas went to Rome. In Livy's Periochae, Fabricius negotiated the return of the prisoners and the mission of Cineas was about organising Pyrrhus' entrance into the city as well as negotiating a peace treaty. In Justin's account, Fabricius made a peace treaty with Pyrrhus and Cineas went to Rome to ratify the treaty. He also wrote that Cineas "found nobody's house open for their reception." Plutarch, instead, had this sequence the other way round. He placed the embassy led by Gaius Fabricius after Cineas' trip to Rome and wrote that Pyrrhus sought friendly terms because he was concerned about the Romans still being belligerent after their defeat and he considered the capture of Rome to be beyond the size of his force. Moreover, a friendly settlement after a victory would enhance his reputation. Cineas offered to free the Roman prisoners, promised to help the Romans with the subjugation of Italy and asked only friendship and immunity for Tarentum in return.

Many senators were inclined towards peace (in Plutarch's account) or a truce (in Cassius Dio's account) because the Romans would have to face a larger army as the Italic allies of Pyrrhus had joined him. However, Appius Claudius Caecus, who was old and blind and had been confined to his house, had himself carried to the senate house in a litter. He said that Pyrrhus was not to be trusted and that a truce (or peace) was not advantageous to the state. He called for Cineas to be dismissed from the city immediately and for Pyrrhus to be told to withdraw to his country and to make his proposals from there. The senate voted unanimously to send away Cineas that very day and to continue the war for so long as Pyrrhus was in Italy.

Appian wrote that the senate decreed to levy two new legions for the consul Publius Valerius Laevinus. He noted that some of the sources of his information reported that Cineas, who was still in Rome, saw the Roman people hastening to enroll and told Pyrrhus that he was fighting against a hydra (a mythological monster with many heads which grew three new heads when one head was cut off). Other sources said that Pyrrhus himself saw that the Roman army was now large because Tiberius Coruncanius, the other consul, "came from Etruria and joined his forces with those of Laevinus." Appian wrote that Cineas also said that Rome was a city of generals and that it seemed a city with many kings. Pyrrhus marched towards Rome plundering everything on the way. He reached Anagnia and decided to postpone the battle because he was heavily laden with and booty. He went to Campania and sent his army to winter camps. Florus wrote that Pyrrhus marched on Rome laid waste the banks of the River Liris and the Roman colony of Fregellae and reached Praeneste (today's Palestrina), which was only twenty miles from Rome and which he nearly seized. Plutarch wrote that Cineas assessed that the Romans now had twice as many soldiers as those who fought at the Battle of Heraclea and that "there were many times as many Romans still who were capable of bearing arms." Justin wrote that Cineas told Pyrrhus that the treaty "was broken off by Appius Claudius" and that Rome appeared to him a city of kings.

Cassius Dio gave a different account of Pyrrhus’ march towards Rome. In his version, it was a march in Tyrrhenian Italy. Publius Valerius Laevinus found out that Pyrrhus wanted to seize Capua (in Campania) and garrisoned it. Pyrrhus set out for the nearby Neapolis (Naples), but he did not accomplish anything and passed on through Etruria "with the object of winning the people there also to his cause." According to Zonaras, Pyrrhus saw that the Etruscans had made a treaty with the Romans, Tiberius Coruncanius, the other consul for 280 BC, was moving towards him and Laevinius was dogging his footsteps. He "became afraid of being cut off on all sides." He withdrew and got close to Campania. Laevinus confronted him with an army which was now larger and "he declared that the Roman legions when cut to pieces grew whole again, hydra-fashion." Pyrrhus declined to join a battle and went back to Tarentum. Because of the fragmentary nature of the surviving texts of Cassius Dio and Zonaras, the dating of these events is uncertain. It could be after Cineas’ trip to Rome. Cassius Dio wrote that the Romans sent another army to Laevinus, who, after seeing to the wounded, followed Pyrrhus and harassed him. They also recalled Tiberius Coruncanius from Etruria and assigned him to guard Rome.

According to Justin, Rome sent some envoys to Ptolemy II, the king of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Pyrrhic War", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.