War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1715)

Prelude

The news that Louis XIV had accepted Charles II's will and that the Second Partition Treaty was dead was a personal blow to William III, who had concluded that Philip V would be nothing more than a French puppet. However, in England The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from about 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. The Viking invasions of the 9th century upset the balance of power between the English kingdoms, and native Anglo-Saxon life in general. The English lands were unified in the 10th century in a reconquest completed by King Æthelstan in 927. many argued that the acceptance of Charles II's will was preferable to a treaty that would have seen France

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from about 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. The Viking invasions of the 9th century upset the balance of power between the English kingdoms, and native Anglo-Saxon life in general. The English lands were unified in the 10th century in a reconquest completed by King Æthelstan in 927. many argued that the acceptance of Charles II's will was preferable to a treaty that would have seen France The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe since the High Middle Ages. It was also an early colonial power, with possessions around the world. Colonial conflicts with Great Britain led to the loss of much of its North American holdings by 1763. The Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic. extend its territory, including the addition of Naples and Sicily which under French control would pose a threat to England's Levantine trade. After the exertions of the Nine Years' War the Tory-dominated House of Commons was keen to prevent further conflict and restore normal commercial activity. Yet to William III France's growing strength made war inevitable, and together with Anthonie Heinsius, Grand Pensionary of Holland and de facto executive head of the Dutch

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe since the High Middle Ages. It was also an early colonial power, with possessions around the world. Colonial conflicts with Great Britain led to the loss of much of its North American holdings by 1763. The Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic. extend its territory, including the addition of Naples and Sicily which under French control would pose a threat to England's Levantine trade. After the exertions of the Nine Years' War the Tory-dominated House of Commons was keen to prevent further conflict and restore normal commercial activity. Yet to William III France's growing strength made war inevitable, and together with Anthonie Heinsius, Grand Pensionary of Holland and de facto executive head of the Dutch The Dutch Republic was a confederation that existed from 1579, during the Dutch Revolt, to 1795. It was a predecessor state of the Netherlands and the first fully independent Dutch nation state. Although the state was small and contained only around 1.5 million inhabitants, it controlled a worldwide network of seafaring trade routes. The income from this trade allowed the Dutch Republic to compete militarily against much larger countries. It amassed a huge fleet of 2,000 ships, initially larger than the fleets of England and France combined. state, he made preparations to gain support. To this end, William III was aided by Louis XIV's own actions which fatally compromised the position of advantage the French king held.

The Dutch Republic was a confederation that existed from 1579, during the Dutch Revolt, to 1795. It was a predecessor state of the Netherlands and the first fully independent Dutch nation state. Although the state was small and contained only around 1.5 million inhabitants, it controlled a worldwide network of seafaring trade routes. The income from this trade allowed the Dutch Republic to compete militarily against much larger countries. It amassed a huge fleet of 2,000 ships, initially larger than the fleets of England and France combined. state, he made preparations to gain support. To this end, William III was aided by Louis XIV's own actions which fatally compromised the position of advantage the French king held.

Louis XIV's first act was an official recognition of Philip V's place in the French line of succession by proclaiming the doctrine of the divine right of kings. This gave rise to the spectre of France and Spain The Spanish Empire was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its predecessor states between 1492 and 1976. One of the largest empires in history, it was the first to usher the European Age of Discovery and achieve a global scale, controlling vast territory. It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, reaching its maximum extent in the 18th century. uniting under a single monarch, a direct contradiction of Charles II's will. Next, in early February 1701 Louis XIV moved to secure the Bourbon succession in the Spanish Netherlands and sent French troops to take over the Dutch-held 'Barrier' fortresses which William III had secured at the Peace of Ryswick. The Spanish Netherlands were of vital strategic interest to the Dutch as they acted as a buffer zone between France and the Republic. But the French incursion was also detrimental to Dutch commercial interests in the region as there was now no prospect of keeping the Scheldt trade restrictions in place – restrictions that up till now had ensured the Republic's position as the primary inlet and outlet for European trade. England also had its own interests in the Spanish Netherlands, and ministers recognised the potential danger posed by an enemy established to the east of the Strait of Dover who, taking advantage of favourable wind and tide, could threaten the British Isles. The French move was designed in part to pressure the States General into recognising Philip as King of Spain – which they soon did – but from William III's perspective, losing the hard-won securities overturned the work of the last twenty years.

The Spanish Empire was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its predecessor states between 1492 and 1976. One of the largest empires in history, it was the first to usher the European Age of Discovery and achieve a global scale, controlling vast territory. It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, reaching its maximum extent in the 18th century. uniting under a single monarch, a direct contradiction of Charles II's will. Next, in early February 1701 Louis XIV moved to secure the Bourbon succession in the Spanish Netherlands and sent French troops to take over the Dutch-held 'Barrier' fortresses which William III had secured at the Peace of Ryswick. The Spanish Netherlands were of vital strategic interest to the Dutch as they acted as a buffer zone between France and the Republic. But the French incursion was also detrimental to Dutch commercial interests in the region as there was now no prospect of keeping the Scheldt trade restrictions in place – restrictions that up till now had ensured the Republic's position as the primary inlet and outlet for European trade. England also had its own interests in the Spanish Netherlands, and ministers recognised the potential danger posed by an enemy established to the east of the Strait of Dover who, taking advantage of favourable wind and tide, could threaten the British Isles. The French move was designed in part to pressure the States General into recognising Philip as King of Spain – which they soon did – but from William III's perspective, losing the hard-won securities overturned the work of the last twenty years.

Louis XIV further alienated the Maritime Powers by pressing the Spanish to grant special privileges to French traders within their empire, thereby squeezing out English and Dutch merchants. To many, Louis XIV was once again acting like the arbiter of Europe, and support for a war policy gained momentum. Although the French king's ambitions and motives were not known for certain, English ministers worked on the assumption that Louis XIV would seek to expand his territory and direct and dominate Spanish affairs. With the threat of a single power dominating Europe and overseas trade, London now undertook to support William III's efforts 'in conjunction with the Emperor and the States General, for the Preservation of the Liberties of Europe, the Property and Peace of England, and for reducing the Exorbitant Power of France.'

Portrait of King William III (1650–1702) by Godfrey Kneller. William III was Louis XIV's greatest long-standing rival, but he died before the declaration of war

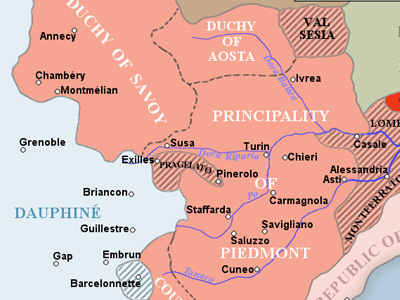

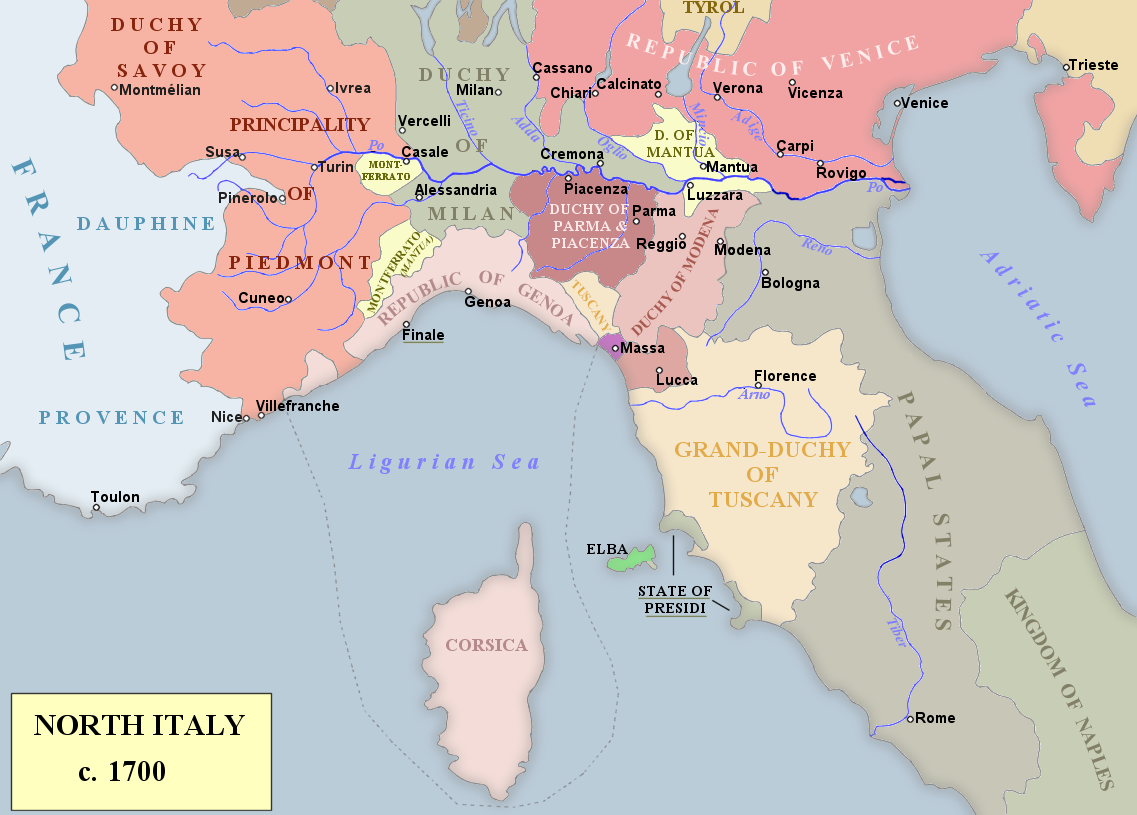

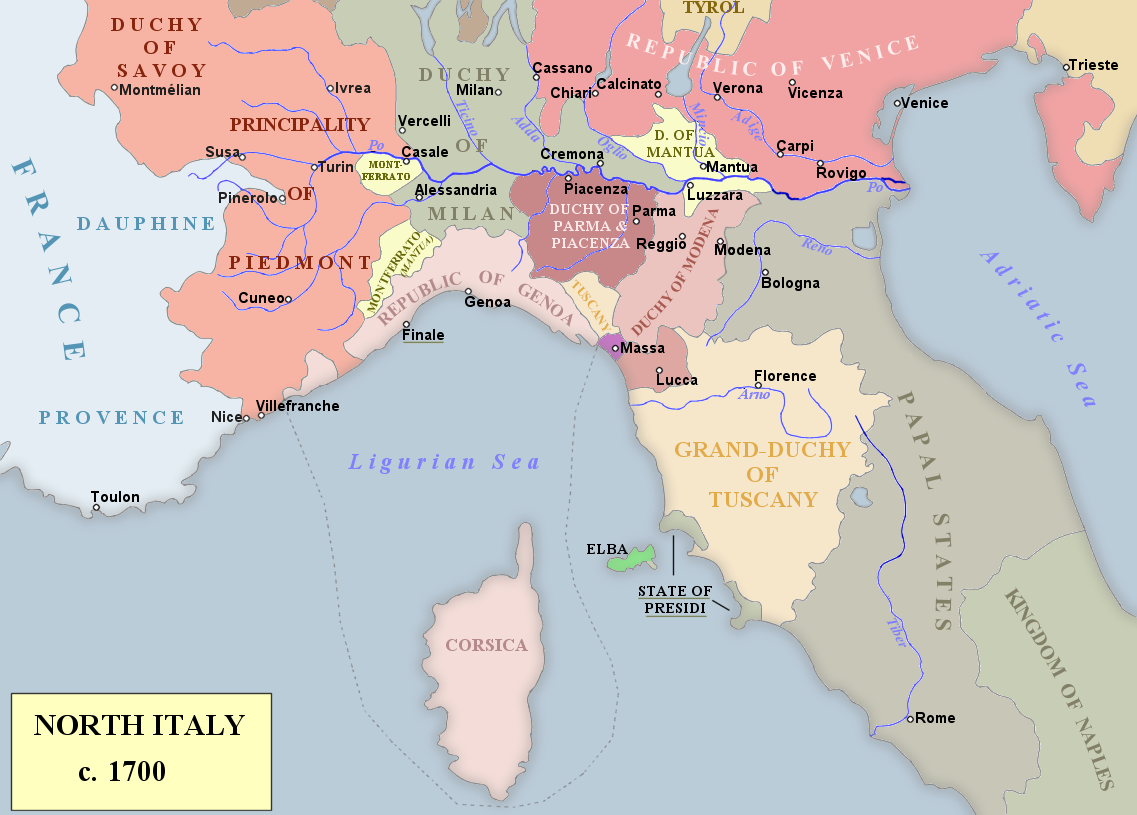

Leopold I moves on Milan

From the start Leopold I had rejected the final will of Charles II: he was determined to keep the Spanish domains in Italy, above all the Duchy of Milan which was seen as the southern key to Austria's The Archduchy of Austria was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire and the nucleus of the Habsburg monarchy. With its capital at Vienna, the archduchy was centered at the Empire's southeastern periphery. The archduchy's history as an imperial state ended with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. It was replaced with the Lower and Upper Austria crown lands of the Austrian Empire. security. Before the opening of hostilities French troops had already been accepted in Milan when its viceroy declared for Philip V; as did the neighbouring Duchy of Mantua by a secret convention of February 1701. The Republic of Venice, the Republic of Genoa, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and the Duchy of Parma (under Papal protection), remained neutral. Farther south the Kingdom of Naples acknowledged Philip V as King of Spain, as did Pope Clement XI who, due to the pro-French leanings of his cardinals, generally followed a policy of benevolent neutrality towards France. Only in the Duchies of Modena and Guastalla – once French troops were expelled at the beginning of the campaign – did the Emperor find support for his cause.

The Archduchy of Austria was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire and the nucleus of the Habsburg monarchy. With its capital at Vienna, the archduchy was centered at the Empire's southeastern periphery. The archduchy's history as an imperial state ended with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. It was replaced with the Lower and Upper Austria crown lands of the Austrian Empire. security. Before the opening of hostilities French troops had already been accepted in Milan when its viceroy declared for Philip V; as did the neighbouring Duchy of Mantua by a secret convention of February 1701. The Republic of Venice, the Republic of Genoa, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and the Duchy of Parma (under Papal protection), remained neutral. Farther south the Kingdom of Naples acknowledged Philip V as King of Spain, as did Pope Clement XI who, due to the pro-French leanings of his cardinals, generally followed a policy of benevolent neutrality towards France. Only in the Duchies of Modena and Guastalla – once French troops were expelled at the beginning of the campaign – did the Emperor find support for his cause.

North Italy. Spanish realms in Italy comprised the Kingdoms of Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia, the Duchy of Milan, the Marquisate of Finale, and the State of Presidi

North Italy. Spanish realms in Italy comprised the Kingdoms of Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia, the Duchy of Milan, the Marquisate of Finale, and the State of Presidi

( Click image to enlarge)

The most significant ruler in northern Italy was Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy, who had a claim to the Spanish thrones through his great-grandmother, daughter of Philip II of Spain. Like the Emperor, the Duke had designs on the neighbouring Duchy of Milan, and he flirted with both Louis XIV and Leopold I to secure his own ambitions. However, the Duke of Anjou's accession to the Spanish thrones and the subsequent dominance of the Bourbons had initially proved to be most persuasive argument, and on 6 April 1701 Victor Amadeus reluctantly renewed his alliance with France. French troops bound for Milan were now permitted to march through Savoyard territory. In return, the Duke was to receive subsidies and the title of supreme commander of the Savoyard and Bourbon armies in Italy (in practice it was only a nominal title), though he was offered no territorial promises. The alliance was sealed with Philip V's marriage to Amadeus' 13-year-old daughter, Maria Luisa.

The French presence in Italy threatened Austria's security. Although Leopold I's recent victory over the Ottoman Turks The Ottoman Empire, also known as the Turkish Empire, was an empire that controlled much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa between the 14th and early 20th centuries. The Ottomans ended the Byzantine Empire with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. The Ottoman Empire's defeat and the occupation of part of its territory by the Allied Powers in the aftermath of World War I resulted in its partitioning and the loss of its Middle Eastern territories. had left his eastern frontiers secure for now, he had been outmanoeuvred diplomatically. In May 1701, therefore, before declaring war, Leopold I sent Prince Eugene of Savoy across the Alps to secure the Duchy of Milan by force. By early June the bulk of Eugene's 30,000 troops had crossed the mountains and into neutral Venice, and on 9 July he defeated a detachment from Marshal Catinat's army at the Battle of Carpi; this was followed with another victory on 1 September when he defeated Catinat's successor, Marshal Villeroi, at the Battle of Chiari. Eugene occupied most of pro-French Mantua territories, yet despite his success he received scant support from Vienna. The collapse of government credit led Leopold I to deplete his army, forcing Eugene into unconventional tactics. On 1 February 1702 he attacked the French headquarters at Cremona. The attack ultimately failed, but Villeroi was captured (later released), compelling the French to pull back behind the Adda. The Bourbons still held the Duchy of Milan, yet the Austrians had demonstrated they could and would fight to protect their interests, furnishing the arguments needed to build an alliance with England and the Dutch Republic.

The Ottoman Empire, also known as the Turkish Empire, was an empire that controlled much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa between the 14th and early 20th centuries. The Ottomans ended the Byzantine Empire with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. The Ottoman Empire's defeat and the occupation of part of its territory by the Allied Powers in the aftermath of World War I resulted in its partitioning and the loss of its Middle Eastern territories. had left his eastern frontiers secure for now, he had been outmanoeuvred diplomatically. In May 1701, therefore, before declaring war, Leopold I sent Prince Eugene of Savoy across the Alps to secure the Duchy of Milan by force. By early June the bulk of Eugene's 30,000 troops had crossed the mountains and into neutral Venice, and on 9 July he defeated a detachment from Marshal Catinat's army at the Battle of Carpi; this was followed with another victory on 1 September when he defeated Catinat's successor, Marshal Villeroi, at the Battle of Chiari. Eugene occupied most of pro-French Mantua territories, yet despite his success he received scant support from Vienna. The collapse of government credit led Leopold I to deplete his army, forcing Eugene into unconventional tactics. On 1 February 1702 he attacked the French headquarters at Cremona. The attack ultimately failed, but Villeroi was captured (later released), compelling the French to pull back behind the Adda. The Bourbons still held the Duchy of Milan, yet the Austrians had demonstrated they could and would fight to protect their interests, furnishing the arguments needed to build an alliance with England and the Dutch Republic.

Grand Alliance Reassembles

Talks had begun at The Hague in March 1701. Despite past antagonisms William III, now nearing death, entrusted the Earl of Marlborough as his political and military successor, appointing him Ambassador Extraordinary at The Hague and commander-in-chief of English and Scottish forces in the Low Countries. Heinsius represented the Dutch while Count Wratislaw, Imperial ambassador in London, negotiated on behalf of the Emperor. Talks with French ambassador, Count d'Avaux, centred around the fate of the Spanish Monarchy, the French troop incursions into the Spanish Netherlands and the Duchy of Milan, and the favourable trade privileges granted to French merchants at the expense of the Maritime Powers. These somewhat insincere talks proved unfruitful, and they collapsed in early August. Nevertheless, concurrent discussions to form an anti-French military alliance between England, the Dutch Republic, and Austria had made significant progress, resulting in the signing of the Second Treaty of Grand Alliance (or, Treaty of The Hague) on 7 September. The overall aims of the Alliance were kept vague: there was no mention of Archduke Charles ascending the Spanish thrones, but the Emperor was to receive an 'equitable and reasonable' satisfaction to the Spanish succession, and the idea that the French and Spanish kingdoms were to remain separate was central to the agreement.

Even after the formation of the Grand Aliance the French King continued to antagonise. On 16 September 1701, the Catholic James II of England (VII of Scotland) – exiled in Saint-Germain since the 'Glorious Revolution' – died. Despite his renunciation of the Jacobites at the Treaty of Ryswick, Louis XIV soon recognised James II's Catholic son, James Francis Edward Stuart, as King 'James III' of England. The French court insisted that granting James the title of King was a mere formality, but English ministers were incredulous and indignant. Louis XIV's declaration seemed a direct challenge to Parliament and the Act of Settlement, which on the death of Anne's only surviving son had fixed the English succession on the Electress Sophia of Hanover (a granddaughter of James VI/I) and her Protestant heirs. In consequence, securing the Protestant succession was soon recognised by the Grand Alliance as one of England's main war aims.

On 19 March 1702, William, King of England and Dutch Stadtholder, died. Anne ascended to the British throne and at once assured the Privy Council of her two main aims: the maintenance of the Protestant succession, and the reduction of the power of France. Anne's accession secured Marlborough's position: she made him Captain-General of her land forces (among other advancements), while Sarah, Marlborough's wife and Anne's long-standing friend, was granted the key positions of the royal household. The Queen also turned to her close adviser (and friend of the Marlboroughs), Sidney Godolphin, and appointed him Lord High Treasurer. In the Dutch Republic William's death brought forth the so-called Second Stadtholderless Period, and in most provinces the anti-Orangist, republican, peace-loving party gained the ascendency. Yet contrary to early French expectation the new regime largely endorsed the foreign policy of William. French domination of the Spanish Netherlands was universally regarded as a direct threat to the survival of the Republic and its trade, and Amsterdam's merchants feared that much of their existing interests with Spain and Spanish America would soon come under French control. Consequently, many leading statesmen of William's later years remained in office, including the experienced Heinsius whose personal relationship with Marlborough was fundamental to the success of the Grand Alliance in the early stages of the war.

With no diplomatic breakthrough made since the signing of the Second Treaty of Grand Alliance, England, the Dutch Republic, and Austria declared war on France on 15 May 1702. Although several estates of the Holy Roman Empire The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars. From the accession of Otto I in 962 until the twelfth century, the Empire was the most powerful monarchy in Europe. The empire reached the apex of territorial expansion and power in the mid-thirteenth century, but overextending led to partial collapse., most notably Bavaria, openly supported the French cause, a majority of estates backed the emperor. On 30 September 1702, the Imperial Diet voted for an imperial war (Reichskrieg) against France.

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars. From the accession of Otto I in 962 until the twelfth century, the Empire was the most powerful monarchy in Europe. The empire reached the apex of territorial expansion and power in the mid-thirteenth century, but overextending led to partial collapse., most notably Bavaria, openly supported the French cause, a majority of estates backed the emperor. On 30 September 1702, the Imperial Diet voted for an imperial war (Reichskrieg) against France.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "War of the Spanish Succession", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.