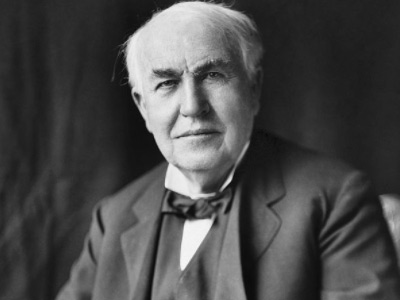

Thomas Edison (1847-1931)

Electric Power Distribution

After devising a commercially viable electric light bulb on October 21, 1879, Edison developed an electric "utility" to compete with the existing gas light utilities. On December 17, 1880, he founded the Edison Illuminating Company, and during the 1880s, he patented a system for electricity distribution. The company established the first investor-owned electric utility in 1882 on Pearl Street Station, New York City. On September 4, 1882, Edison switched on his Pearl Street generating station's electrical power distribution system, which provided 110 volts direct current (DC) to 59 customers in lower Manhattan.

In January 1882, Edison switched on the first steam-generating power station at Holborn Viaduct in London England The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in Northwestern Europe that comprised the entirety of the British Isles between 1801 and 1922. The United Kingdom, having financed the European coalition that defeated France during the Napoleonic Wars, developed a large Royal Navy that enabled the British Empire to become the foremost world power for the next century.. The DC supply system provided electricity supplies to street lamps and several private dwellings within a short distance of the station. On January 19, 1883, the first standardized incandescent electric lighting system employing overhead wires began service in Roselle, New Jersey United States

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in Northwestern Europe that comprised the entirety of the British Isles between 1801 and 1922. The United Kingdom, having financed the European coalition that defeated France during the Napoleonic Wars, developed a large Royal Navy that enabled the British Empire to become the foremost world power for the next century.. The DC supply system provided electricity supplies to street lamps and several private dwellings within a short distance of the station. On January 19, 1883, the first standardized incandescent electric lighting system employing overhead wires began service in Roselle, New Jersey United States The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, DC, and the most populous city and financial center is New York City..

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, DC, and the most populous city and financial center is New York City..

War of Currents

As Edison expanded his direct current (DC) power delivery system, he received stiff competition from companies installing alternating current (AC) systems. From the early 1880s AC arc lighting systems for streets and large spaces had been an expanding business in the US. With the development of transformers in Europe and by Westinghouse Electric in the US in 1885–1886, it became possible to transmit AC long distances over thinner and cheaper wires, and "step down" the voltage at the destination for distribution to users. This allowed AC to be used in street lighting and in lighting for small business and domestic customers, the market Edison's patented low voltage DC incandescent lamp system was designed to supply. Edison's DC empire suffered from one of its chief drawbacks: it was suitable only for the high density of customers found in large cities. Edison's DC plants could not deliver electricity to customers more than one mile from the plant, and left a patchwork of unsupplied customers between plants. Small cities and rural areas could not afford an Edison style system at all, leaving a large part of the market without electrical service. AC companies expanded into this gap.

Edison expressed views that AC was unworkable and the high voltages used were dangerous. As George Westinghouse installed his first AC systems in 1886, Thomas Edison struck out personally against his chief rival stating, "Just as certain as death, Westinghouse will kill a customer within six months after he puts in a system of any size. He has got a new thing and it will require a great deal of experimenting to get it working practically." Many reasons have been suggested for Edison's anti-AC stance. One notion is that the inventor could not grasp the more abstract theories behind AC and was trying to avoid developing a system he did not understand. Edison also appeared to have been worried about the high voltage from misinstalled AC systems killing customers and hurting the sales of electric power systems in general. Primary was the fact that Edison Electric based their design on low voltage DC and switching a standard after they had installed over 100 systems was, in Edison's mind, out of the question. By the end of 1887, Edison Electric was losing market share to Westinghouse, who had built 68 AC-based power stations to Edison's 121 DC-based stations. To make matters worse for Edison, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company of Lynn, Massachusetts (another AC-based competitor) built 22 power stations.

Parallel to expanding competition between Edison and the AC companies was rising public furor over a series of deaths in the spring of 1888 caused by pole mounted high voltage alternating current lines. This turned into a media frenzy against high voltage alternating current and the seemingly greedy and callous lighting companies that used it. Edison took advantage of the public perception of AC as dangerous, and joined with self-styled New York anti-AC crusader Harold P. Brown in a propaganda campaign, aiding Brown in the public electrocution of animals with AC, and supported legislation to control and severely limit AC installations and voltages (to the point of making it an ineffective power delivery system) in what was now being referred to as a "battle of currents". The development of the electric chair was used in an attempt to portray AC as having a greater lethal potential than DC and smear Westinghouse at the same time via Edison colluding with Brown and Westinghouse's chief AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, to make sure the first electric chair was powered by a Westinghouse AC generator.

Thomas Edison's staunch anti-AC tactics were not sitting well with his own stockholders. By the early 1890s, Edison's company was generating much smaller profits than its AC rivals, and the War of Currents would come to an end in 1892 with Edison forced out of controlling his own company. That year, the financier J.P. Morgan engineered a merger of Edison General Electric with Thomson-Houston that put the board of Thomson-Houston in charge of the new company called General Electric. General Electric now controlled three-quarters of the US electrical business and would compete with Westinghouse for the AC market.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Thomas Edison (1847-1931)", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.