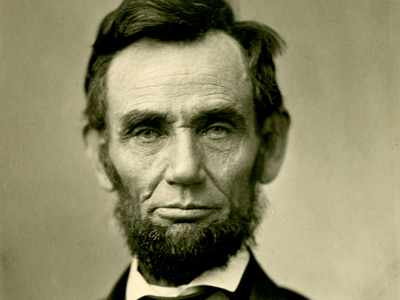

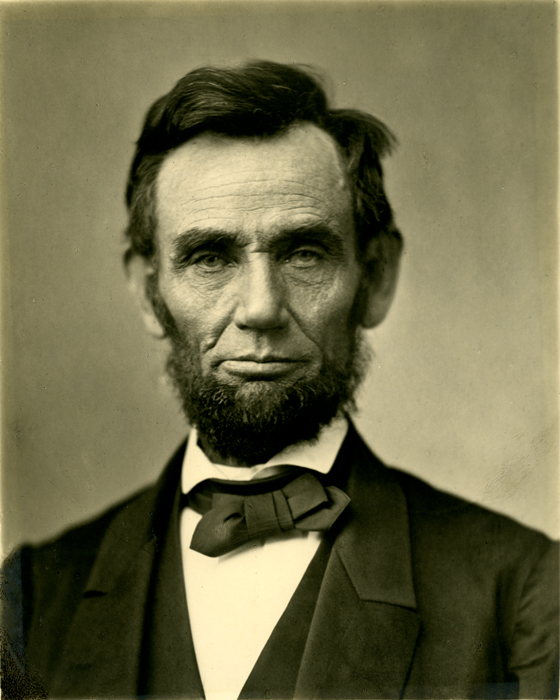

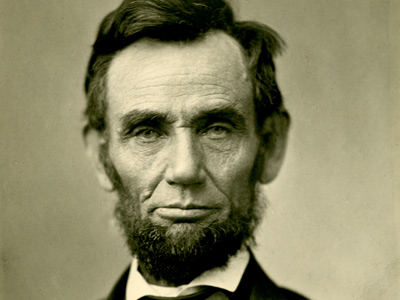

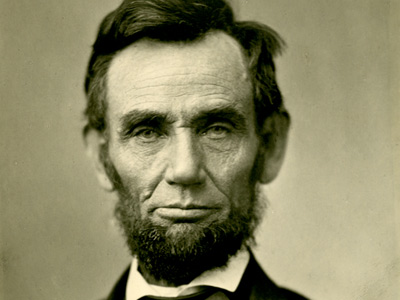

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)

Emergence as Republican Leader

The debate over the status of slavery in the territories exacerbated sectional tensions between the slave-holding South and the North, and the Compromise of 1850 failed to defuse the issue. In the early 1850s, Lincoln supported efforts for sectional mediation, and his 1852 eulogy for Henry Clay focused on the latter's support for gradual emancipation and opposition to "both extremes" on the slavery issue. As the 1850s progressed, the debate over slavery in the Nebraska Territory and Kansas Territory became particularly acrimonious, and Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois proposed popular sovereignty as a compromise measure; the proposal would take the issue of slavery out of the hands of Congress by allowing the people of each territory to decide the status of slavery themselves. The proposal alarmed many Northerners, who hoped to stop the spread of slavery into the territories. Despite this Northern opposition, Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act narrowly passed Congress in May 1854.

For months after its passage, Lincoln did not publicly comment on the Kansas-Nebraska Act, but he came to strongly oppose it. On October 16, 1854, in his "Peoria Speech", Lincoln declared his opposition to slavery, which he repeated en route to the presidency. Speaking in his Kentucky accent, with a very powerful voice, he said the Kansas Act had a "declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world ..." Lincoln's attacks on the Kansas-Nebraska Act marked his return to political life.

Nationally, the Whigs were irreparably split by the Kansas–Nebraska Act and other efforts to compromise on the slavery issue. Reflecting the demise of his party, Lincoln would write in 1855, "I think I am a Whig, but others say there are no Whigs, and that I am an abolitionist [...] I do no more than oppose the extension of slavery." Drawing on the antislavery portion of the Whig Party, and combining Free Soil, Liberty, and antislavery Democratic Party members, the new Republican Party formed as a northern party dedicated to antislavery. Lincoln resisted early attempts to recruit him to the new party, fearing that it would serve as a platform for extreme abolitionists. Lincoln also still hoped to rejuvenate the ailing Whig Party, though he bemoaned his party's growing closeness with the nativist Know Nothing movement.

Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature as Whig. In the aftermath of the 1854 elections, which showed the power and popularity of the movement opposed to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Lincoln declined to take his seat and instead sought election to the United States Senate. At that time, senators were elected by the state legislature. After leading in the first six rounds of voting, but unable to obtain a majority, Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull. Trumbull was an antislavery Democrat, and had received few votes in the earlier ballots; his supporters, also antislavery Democrats, had vowed not to support any Whig. Lincoln's decision to withdraw enabled his Whig supporters and Trumbull's antislavery Democrats to combine and defeat the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson.

In part due to the ongoing violent political confrontations in the Kansas, opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act remained strong in Illinois and throughout the North. As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln abandoned the defunct Whig Party in favor of the Republicans. He attended the May 1856 Bloomington Convention, which formally established the Illinois Republican Party. The convention platform asserted that Congress had the right to regulate slavery in the territories and called for the immediate admission of Kansas as a free state. Lincoln gave the final speech of the convention, in which he endorsed the party platform and called for the preservation of the Union. At the June 1856 Republican National Convention, Lincoln received significant support on the vice presidential ballot, though the party nominated a ticket of John C. Frémont and William Dayton. Lincoln strongly supported the Republican ticket, campaigning for the party throughout Illinois. The Democrats nominated former Ambassador James Buchanan, who had been out of the country since 1853 and thus had avoided the debate over slavery in the territories, while the Know Nothings nominated former Whig President Millard Fillmore. In the 1856 elections, Buchanan defeated both his challengers, but Frémont won several Northern states and Republican William Henry Bissell won election as Governor of Illinois. Though Lincoln did not himself win office, his vigorous campaigning had made him the leading Republican in Illinois United States The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, DC, and the most populous city and financial center is New York City..

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, DC, and the most populous city and financial center is New York City..

Eric Foner (2010) contrasts the abolitionists and anti-slavery Radical Republicans of the Northeast who saw slavery as a sin, with the conservative Republicans who thought it was bad because it hurt white people and blocked progress. Foner argues that Lincoln was a moderate in the middle, opposing slavery primarily because it violated the republicanism principles of the Founding Fathers, especially the equality of all men and democratic self-government as expressed in the Declaration of Independence.

In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford; Chief Justice Roger B. Taney opined that blacks were not citizens, and derived no rights from the Constitution. While many Democrats hoped that Dred Scott would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, the decision sparked further outrage in the North. Lincoln denounced the decision, alleging it was the product of a conspiracy of Democrats to support the Slave Power. Lincoln argued, "The authors of the Declaration of Independence never intended 'to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity', but they 'did consider all men created equal—equal in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness'."

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Abraham Lincoln", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.