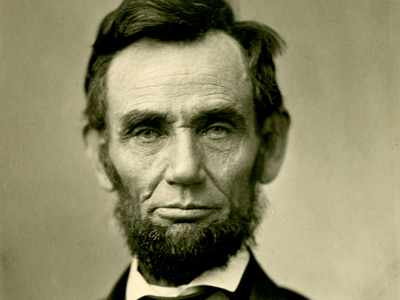

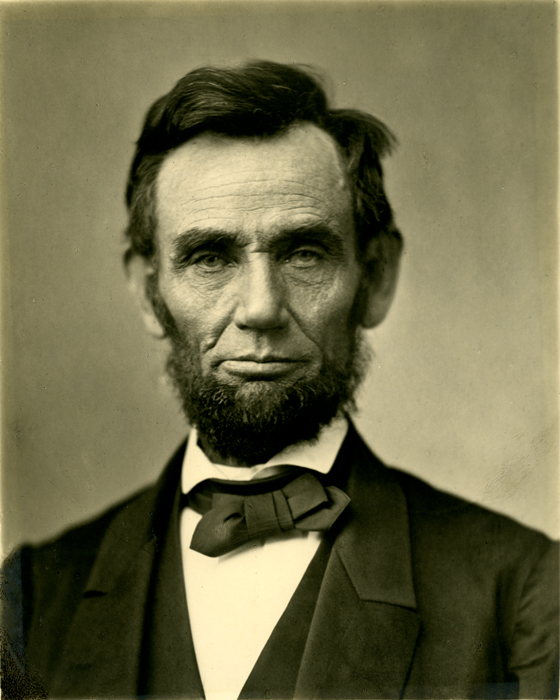

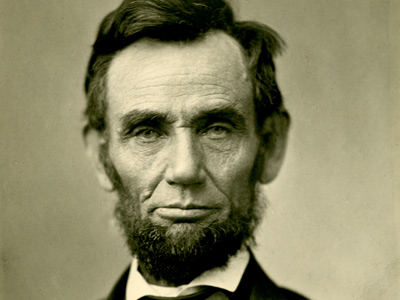

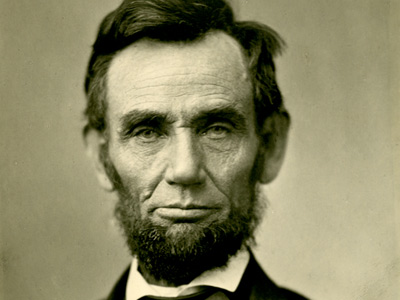

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)

Lincoln–Douglas Debates and Cooper Union Speech

Douglas was up for re-election in 1858, and Lincoln hoped to defeat the powerful Illinois Democrat. With the former Democrat Trumbull now serving as a Republican Senator, many in the party felt that a former Whig should be nominated in 1858, and Lincoln's 1856 campaigning and willingness to support Trumbull in 1854 had earned him favor in the party. Some eastern Republicans favored the reelection of Douglas for the Senate in 1858, since he had led the opposition to the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state. But many Illinois Republicans resented this eastern interference. For the first time, Illinois Republicans held a convention to agree upon a Senate candidate, and Lincoln won the party's Senate nomination with little opposition.

Accepting the nomination, Lincoln delivered his House Divided Speech, drawing on Mark 3:25, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other." The speech created an evocative image of the danger of disunion caused by the slavery debate, and rallied Republicans across the North. The stage was then set for the campaign for statewide election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas as its U.S. senator. On being informed of Lincoln's nomination, Douglas stated "[Lincoln] is the strong man of the party...and if I beat him, my victory will be hardly won."

The Senate campaign featured the seven Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858, the most famous political debates in American history. The principals stood in stark contrast both physically and politically. Lincoln warned that "The Slave Power" was threatening the values of republicanism, and accused Douglas of distorting the values of the Founding Fathers that all men are created equal, while Douglas emphasized his Freeport Doctrine, that local settlers were free to choose whether to allow slavery or not, and accused Lincoln of having joined the abolitionists. The debates had an atmosphere of a prize fight and drew crowds in the thousands. Lincoln stated Douglas' popular sovereignty theory was a threat to the nation's morality and that Douglas represented a conspiracy to extend slavery to free states. Douglas said that Lincoln was defying the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court and the Dred Scott decision.

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas to the Senate. Despite the bitterness of the defeat for Lincoln, his articulation of the issues gave him a national political reputation. In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper which was consistently supportive; most of the state's 130,000 German Americans voted Democratic but there was Republican support that a German-language paper could mobilize. In the aftermath of the 1858 election, newspapers frequently mentioned Lincoln as a potential Republican presidential candidate in 1860, with William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Simon Cameron looming as rivals for the nomination. While Lincoln was popular in the Midwest, he lacked support in the Northeast, and was unsure as to whether he should seek the presidency. In January 1860, Lincoln told a group of political allies that he would accept the 1860 presidential nomination if offered, and in the following months several local papers endorsed Lincoln for president.

On February 27, 1860, New York party leaders invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union to a group of powerful Republicans. Lincoln argued that the Founding Fathers had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery. Lincoln insisted the moral foundation of the Republicans required opposition to slavery, and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong". Despite his inelegant appearance—many in the audience thought him awkward and even ugly —Lincoln demonstrated an intellectual leadership that brought him into the front ranks of the party and into contention for the Republican presidential nomination. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience."

Historian Donald described the speech as a "superb political move for an unannounced candidate, to appear in one rival's (Seward) own state at an event sponsored by the second rival's (Chase) loyalists, while not mentioning either by name during its delivery". In response to an inquiry about his presidential intentions, Lincoln said, "The taste is in my mouth a little."

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Abraham Lincoln", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.