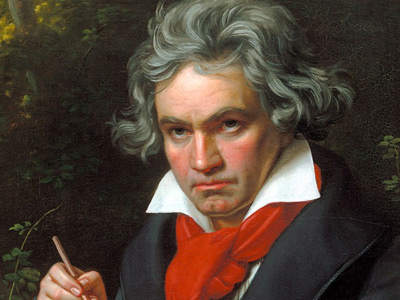

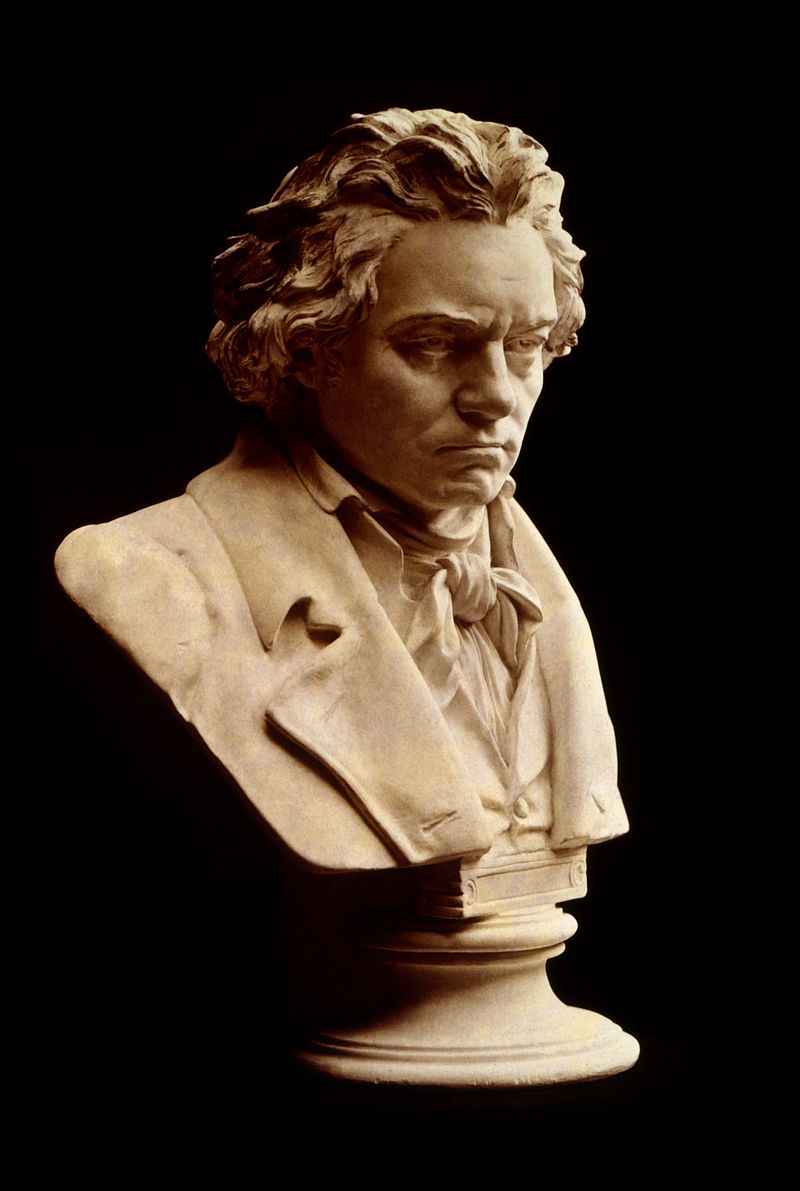

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Late Works

Beethoven began a renewed study of older music, including works by J. S. Bach and Handel, that were then being published in the first attempts at complete editions. He composed the overture The Consecration of the House, which was the first work to attempt to incorporate these influences. A new style emerged, now called his "late period". He returned to the keyboard to compose his first piano sonatas in almost a decade: the works of the late period are commonly held to include the last five piano sonatas and the Diabelli Variations, the last two sonatas for cello and piano, the late string quartets, and two works for very large forces: the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony.

By early 1818 Beethoven's health had improved, and his nephew moved in with him in January. On the downside, his hearing had deteriorated to the point that conversation became difficult, necessitating the use of conversation books. His household management had also improved somewhat; Nanette Streicher, who had assisted in his care during his illness, continued to provide some support, and he finally found a skilled cook. His musical output in 1818 was still somewhat reduced, but included song collections and the "Hammerklavier" Sonata, as well as sketches for two symphonies that eventually coalesced into the epic Ninth. In 1819 he was again preoccupied by the legal processes around Karl, and began work on the Diabelli Variations and the Missa Solemnis.

For the next few years he continued to work on the Missa, composing piano sonatas and bagatelles to satisfy the demands of publishers and the need for income, and completing the Diabelli Variations. He was ill again for an extended time in 1821, and completed the Missa in 1823, three years after its original due date. He also opened discussions with his publishers over the possibility of producing a complete edition of his work, an idea that was arguably not fully realised until 1971. Beethoven's brother Johann began to take a hand in his business affairs, much in the way Kaspar had earlier, locating older unpublished works to offer for publication and offering the Missa to multiple publishers with the goal of getting a higher price for it.

Two commissions in 1822 improved Beethoven's financial prospects. The Philharmonic Society of London offered a commission for a symphony, and Prince Nikolas Golitsin of St. Petersburg offered to pay Beethoven's price for three string quartets. The first of these commissions spurred Beethoven to finish the Ninth Symphony, which was first performed, along with the Missa Solemnis, on 7 May 1824, to great acclaim at the Kärntnertortheater. The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung gushed, "inexhaustible genius had shown us a new world," and Carl Czerny wrote that his symphony "breathes such a fresh, lively, indeed youthful spirit ... so much power, innovation, and beauty as ever [came] from the head of this original man, although he certainly sometimes led the old wigs to shake their heads." Unlike his more lucrative earlier concerts, this did not make Beethoven much money, as the expenses of mounting it were significantly higher. A second concert on 24 May, in which the producer guaranteed Beethoven a minimum fee, was poorly attended; nephew Karl noted that "many people [had] already gone into the country." It was Beethoven's last public concert.

Beethoven then turned to writing the string quartets for Golitsin. This series of quartets, known as the "Late Quartets," went far beyond what musicians or audiences were ready for at that time. One musician commented that "we know there is something there, but we do not know what it is." Composer Louis Spohr called them "indecipherable, uncorrected horrors." Opinion has changed considerably from the time of their first bewildered reception: their forms and ideas inspired musicians and composers including Richard Wagner and Béla Bartók, and continue to do so. Of the late quartets, Beethoven's favourite was the Fourteenth Quartet, op. 131 in C♯ minor, which he rated as his most perfect single work. The last musical wish of Schubert was to hear the Op. 131 quartet, which he did on 14 November 1828, five days before his death.

Beethoven wrote the last quartets amidst failing health. In April 1825 he was bedridden, and remained ill for about a month. The illness—or more precisely, his recovery from it—is remembered for having given rise to the deeply felt slow movement of the Fifteenth Quartet, which Beethoven called "Holy song of thanks ('Heiliger Dankgesang') to the divinity, from one made well." He went on to complete the quartets now numbered Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Sixteenth. The last work completed by Beethoven was the substitute final movement of the Thirteenth Quartet, which replaced the difficult Große Fuge. Shortly thereafter, in December 1826, illness struck again, with episodes of vomiting and diarrhoea that nearly ended his life.

In 1825, his nine symphonies were performed in a cycle for the first time, by the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Johann Philipp Christian Schulz. This was repeated in 1826.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.