Great Roman Civil War (49–45 BC)

March on Rome and the early Hispanian campaign

Caesar's march on Rome was a triumphal progress. The Senate, not knowing that Caesar possessed only a single legion, feared the worst and supported Pompey. Pompey declared that Rome could not be defended; he escaped to Capua with those politicians who supported him, the aristocratic Optimates and the regnant consuls. Cicero later characterised Pompey's "outward sign of weakness" as allowing Caesar's consolidation of power.

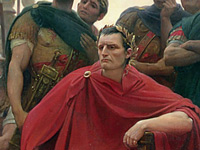

Despite having retreated into central Italy, Pompey and the Senatorial forces disposed of at least two legions: some 11,500 soldiers and some hastily levied Italian troops commanded by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (Domitius). As Caesar Julius Caesar (100-44 BC), was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. Caesar is considered by many historians to be one of the greatest military commanders in history. Julius Caesar » progressed southwards, Pompey retreated towards Brundisium, initially ordering Domitius (engaged in raising troops in Etruria) to stop Caesar's movement on Rome from the direction of the Adriatic seaboard.

Julius Caesar (100-44 BC), was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. Caesar is considered by many historians to be one of the greatest military commanders in history. Julius Caesar » progressed southwards, Pompey retreated towards Brundisium, initially ordering Domitius (engaged in raising troops in Etruria) to stop Caesar's movement on Rome from the direction of the Adriatic seaboard.

Belatedly, Pompey ordered Domitius to retreat south also, and make junction with Pompey's forces. Domitius mostly ignored Pompey's orders, and, after being isolated and trapped near Corfinium was forced to surrender almost thirty cohorts of troops (about three legions), most of whom promptly joined Caesar's army.

Pompey escaped to Brundisium, there awaiting sea transport for his legions, to Epirus, in the Republic's eastern Greek provinces, expecting his influence to yield money and armies for a maritime blockade of Italy proper. Meanwhile, the aristocrats (the Optimates)—including Metellus Scipio and Cato the Younger—joined Pompey there, whilst leaving a rear guard at Capua.

Caesar pursued Pompey to Brundisium, expecting restoration of their alliance of ten years prior; to wit, throughout the Great Roman Civil War's early stages, Caesar frequently proposed to Pompey that they, both generals, sheathe their swords. Pompey refused, legalistically arguing that Caesar was his subordinate and thus was obligated to cease campaigning and dismiss his armies before any negotiation. As the Senate's chosen commander, and with the backing of at least one of the current consuls, Pompey commanded legitimacy, whereas Caesar's military crossing of the Rubicon River frontier rendered him a de jure enemy of the Senate and People of Rome. Nevertheless, in March 49 BC, Pompey escaped Caesar at Brundisium, fleeing by sea to Epirus, in Roman Greece.

Taking advantage of Pompey's absence from the Italian mainland, Caesar effected an astonishingly fast 27-day, north-bound forced march to destroy, in the Battle of Ilerda, Hispania's politically leader-less Pompeian army, commanded by the legates, Lucius Afranius (Afranius) and Marcus Petreius (Petreius), afterwards pacifying Roman Hispania; in campaign, the Caesarian forces—six legions, 3,000 cavalry (Gallic campaign veterans), and Caesar's 900-horse personal bodyguard—suffered 70 men killed in action, while the Pompeian forces lost 200 men killed and 600 wounded.

Returned to Rome in December of 49 BC, Caesar was appointed Dictator, with Mark Antony as his Master of the Horse. Caesar kept his dictatorship for eleven days, tenure sufficient to win him a second term as consul with Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus as his colleague. Afterwards, Caesar renewed pursuit of Pompey, then in Roman Greece.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Caesar's Civil War", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.