Soccer

Soccer Formations

In association football, the formation describes how the players in a team are positioned on the pitch. Different formations can be used depending on whether a team wishes to play more attacking or defensive football.

Formations are used in both professional and amateur football matches. In amateur matches, however, these tactics are sometimes adhered to less strictly due to the lesser significance of the occasion. Skill and discipline on the part of the players is also needed to implement a given formation effectively in professional football. Formations need to be chosen bearing in mind which players are available. Some of the formations below were created to address deficits or strengths in different types of players.

Formations are described by categorizing the players (not including the goalkeeper) according to their positioning along (not across) the pitch, with the more defensive players given first. For example, 4–4–2 means four defenders, four midfielders, and two forwards.

Traditionally those within the same category (for example the 4 midfielders in 4–4–2) would generally play as a fairly flat line across the pitch, with those out wide often playing in a slightly more advanced position. In many modern formations this is not the case, which has led to some analysts splitting the categories in two separate bands, leading to four or even five numbered formations. A common example is 4–2–1–3, where the midfielders are split into two defensive and one offensive player; as such this formation can be considered a kind of 4–3–3.

The numbering system was not present until the 4–2–4 system was developed in the 1950s.

Choice and Uses of Formations

The choice of formation is often related to the type of players available to the coach.

- Narrow formations. Teams with a surfeit of central midfielders, or teams who attack best through the centre, may choose to adopt narrow formations such as the 4–1–2–1–2 or the 4–3–2–1 which allow teams to field up to four or five central midfielders in the team. Narrow formations however depend on the full-backs (the flank players in the "4") to provide width and to advance upfield as frequently as possible to supplement the attack in wide areas.

- Wide formations. Teams with a surfeit of forwards and wingers may choose to adopt formations such as 4–2–3–1, 3–5–2 and 4–3–3, which commit forwards and wingers high up the pitch. Wide formations allow the attacking team to stretch play and cause the defending team to cover more ground.

Teams may change formations during a game to aid their cause:

- Change to attacking formations. When chasing a game for a desirable result, teams tend to sacrifice a defensive player or a midfield player for a forward in order to chase a result. An example of such a change is a change from 4–5–1 to 4–4–2, 3–5–2 to 3–4–3, or even 5–3–2 to 4–3–3.

- Change to defensive formations. When a team is in the lead, or wishes to protect the scoreline of a game, the coach may choose to revert to a more defensive structure by removing a forward for a more defensive player. The extra player in defense or midfield adds solidity by giving the team more legs to chase opponents and recover possession. An example of such a change is a change from 4–4–2 to 5–3–2, 3–5–2 to 4–5–1, or even 4–4–2 to 5–4–1.

Formations can be deceptive in analyzing a particular team's style of play. For instance, a team that plays a nominally attacking 4–3–3 formation can quickly revert to a 4–5–1 if a coach instructs two of the three forwards to track back in midfield.

Early Formations

In the football matches of the 19th century defensive football was not played, and the line-ups reflected the all-attacking nature of these games.

In the first international game, Scotland against England on 30 November 1872, England played with seven or eight forwards in a 1–1–8 or 1–2–7 formation, and Scotland with six, in a 2–2–6 formation. For England, one player would remain in defense, picking up loose balls, and one or two players would hang around midfield and kick the ball upfield for the other players to chase. The English style of play at the time was all about individual excellence and English players were renowned for their dribbling skills. Players would attempt to take the ball forward as far as possible and only when they could proceed no further, would they kick it ahead for someone else to chase. Scotland surprised England by actually passing the ball among players. The Scottish outfield players were organized into pairs and each player would always attempt to pass the ball to his assigned partner. Ironically, with so much attention given to attacking play, the game ended in a 0–0 draw.

Classic Formations

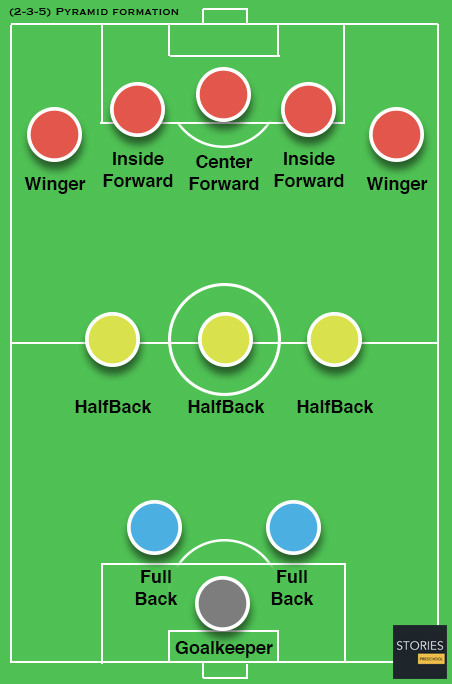

2-3-5 (Pyramid) Formation

The 2–3–5 was originally known as the "Pyramid", with the numerical formation being referenced retrospectively. By the 1890s, it was the standard formation in England and had spread all over the world. With some variations, it was used by most top level teams up to the 1940s. View Soccer Formation »

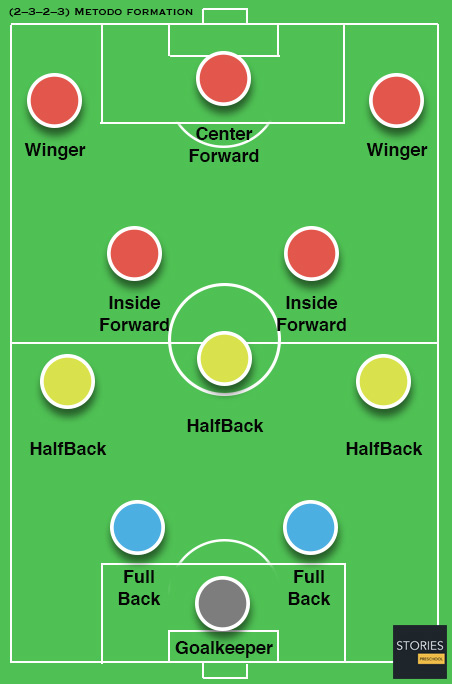

2–3–2–3 (Metodo) Formation

The Metodo was devised by Vittorio Pozzo, coach of the Italian national team in the 1930s. It was a derivation of the Danubian School. The system was based on the 2–3–5 formation, Pozzo realized that his half-backs would need some more support in order to be superior to the opponents' midfield, so he pulled two of the forwards to just in front of midfield, creating a 2–3–2–3 formation. View Soccer Formation »

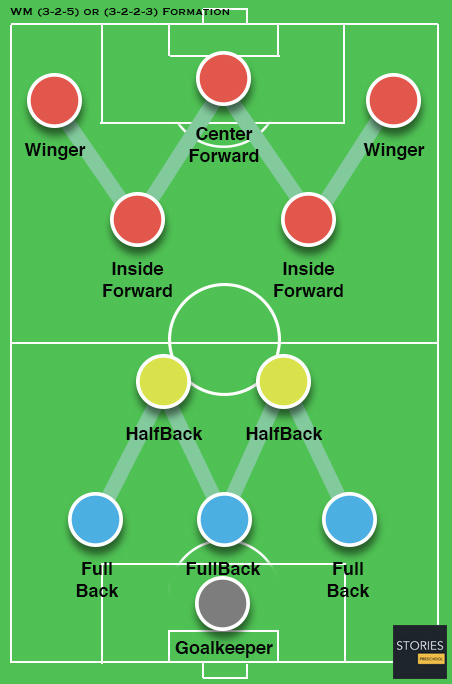

3-2-5 or 3–2–2–3 (WM) Formation

The WM system, known for the shapes described by the positions of the players, was created in the mid-1920s by Herbert Chapman of Arsenal to counter a change in the offside law in 1925. The change had reduced the number of opposition players that attackers needed between themselves and the goal-line from three to two. View Soccer Formation »

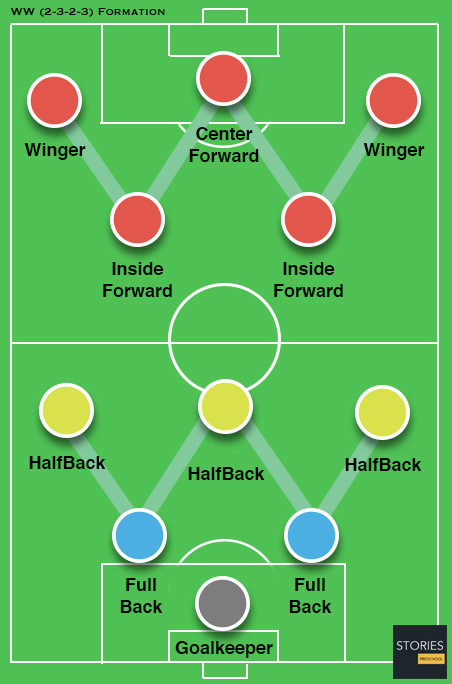

2-3-2-3 (WW) Formation

The WW was a development of the WM created by the Hungarian coach Márton Bukovi who turned the 3–2–5 WM into a 2–3–2–3 by effectively turning the M "upside down". The lack of an effective centre-forward in his team necessitated moving this player back to midfield to create a playmaker, with a midfielder instructed to focus on defense. View Soccer Formation »

3–3–4 Formation

The 3–3–4 formation was similar to the WW, with the notable exception of having an inside-forward (as opposed to centre-forward) deployed as a midfield schemer alongside the two wing-halves. This formation would be commonplace during the 1950s and early 1960s. View Soccer Formation »

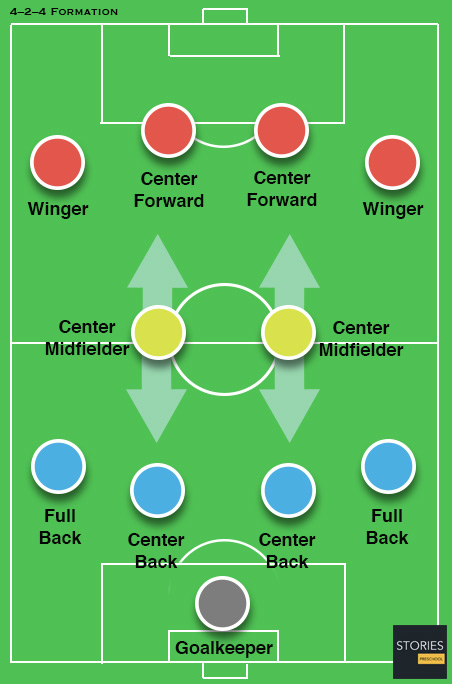

4–2–4 Formation

The 4–2–4 formation attempts to combine a strong attack with a strong defense, and was conceived as a reaction to WM's stiffness. It could also be considered a further development of the WW. The 4–2–4 was the first formation to be described using numbers. View Soccer Formation »

Common Modern Formations

The following formations are used in modern football. The formations are flexible allowing tailoring to the needs of a team, as well as to the players available. Variations of any given formation include changes in positioning of players, as well as replacement of a traditional defender by a sweeper.

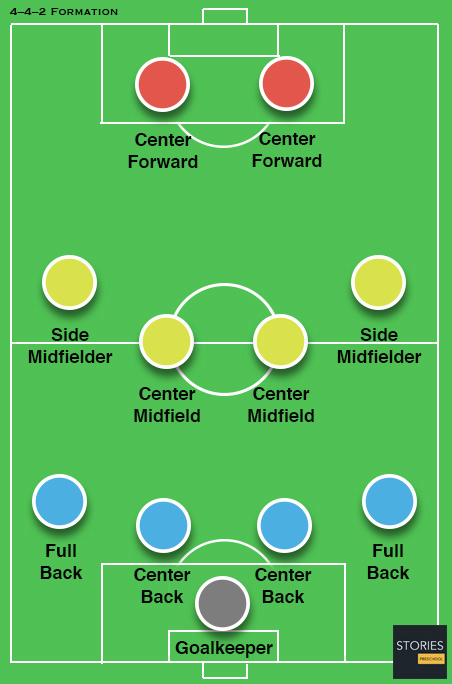

4–4–2 Formation

This formation was the most common in football in the 1990s and early 2000s, so well known that it inspired the title of the magazine FourFourTwo. The midfielders are required to work hard to support both the defense and the attack: typically one of the central midfielders is expected to go upfield as often as possible to support the forward pair, while the other will play a "holding role", shielding the defense. View Soccer Formation »

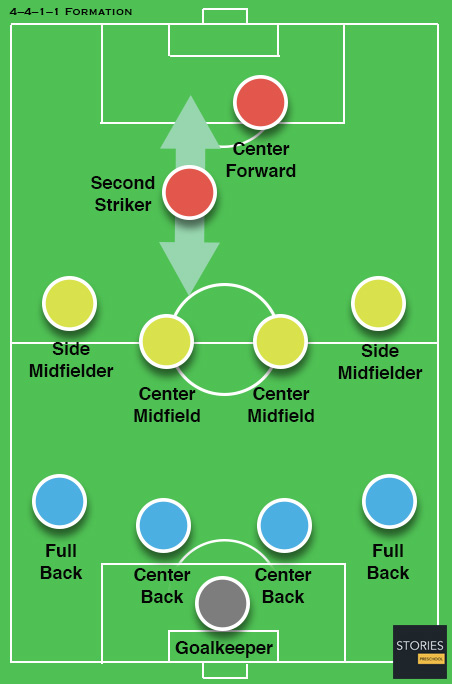

4–4–1–1 Formation

A variation of 4–4–2 with one of the strikers playing "in the hole", or as a "second striker", slightly behind their partner. The second striker is generally a more creative player, the playmaker, who can drop into midfield to pick up the ball before running with it or passing to team-mates. View Soccer Formation »

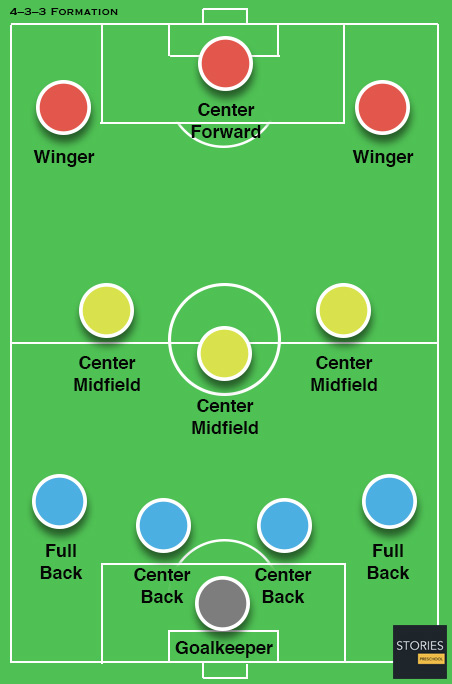

4–3–3 Formation

The 4–3–3 was a development of the 4–2–4, and was played by the Brazilian national team in the 1962 World Cup, although a 4-3-3 had also previously been used by the Uruguayan national team in the 1950 and 1954 World Cups. The extra player in midfield allows a stronger defense, and the midfield could be staggered for different effects. View Soccer Formation »

4–3–1–2 Formation

A variation of the 4–3–3 wherein a striker gives way to a central attacking midfielder. The formation focuses on the attacking midfielder moving play through the centre with the strikers on either side. It is a much narrower setup in comparison to the 4–3–3 and is usually dependent on the "1" to create chances. View Soccer Formation »

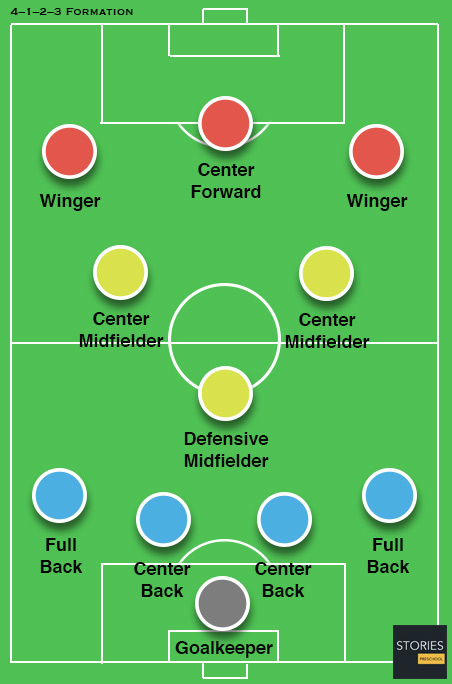

4–1–2–3 Formation

A variation of the 4–3–3 with a defensive midfielder, two central midfielders and a fluid front three. View Soccer Formation »

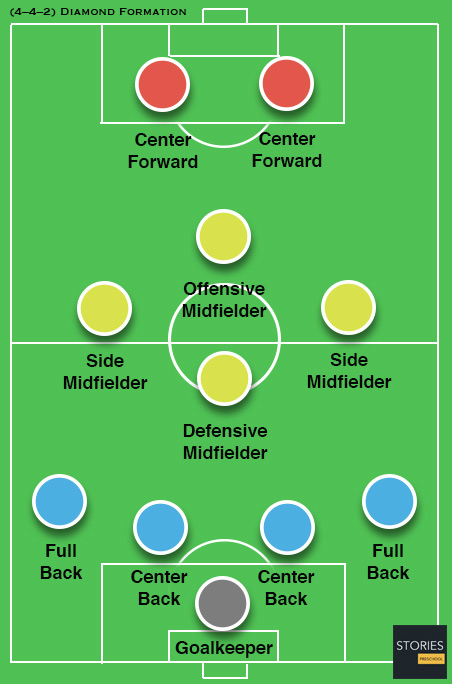

(4–4–2) Diamond Formation

The 4–4–2 diamond (also described as 4–1–2–1–2) staggers the midfield. The width in the team has to come from the full-backs pushing forward. The defensive midfielder is sometimes used as a deep lying playmaker. Its most famous example was Carlo Ancelotti's Milan, which won the 2003 UEFA Champions League Final and made Milan runners-up in 2005. View Soccer Formation »

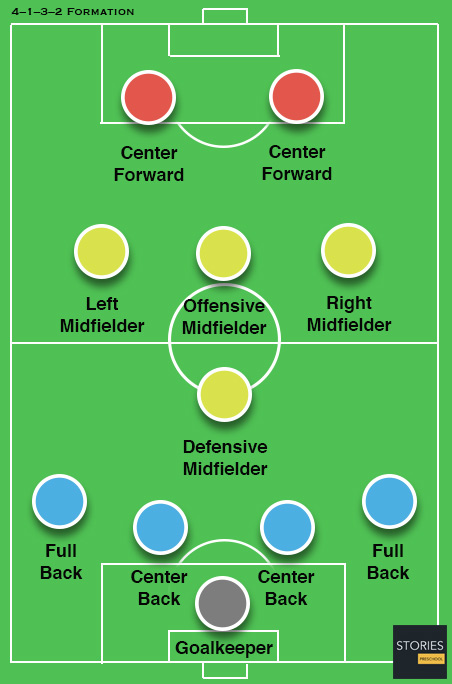

4–1–3–2 Formation

The 4–1–3–2 is a variation of the 4–1–2–1–2 and features a strong and talented defensive centre midfielder. This allows the remaining three midfielders to play farther forward and more aggressively, and also allows them to pass back to their defensive mid when setting up a play or recovering from a counterattack. View Soccer Formation »

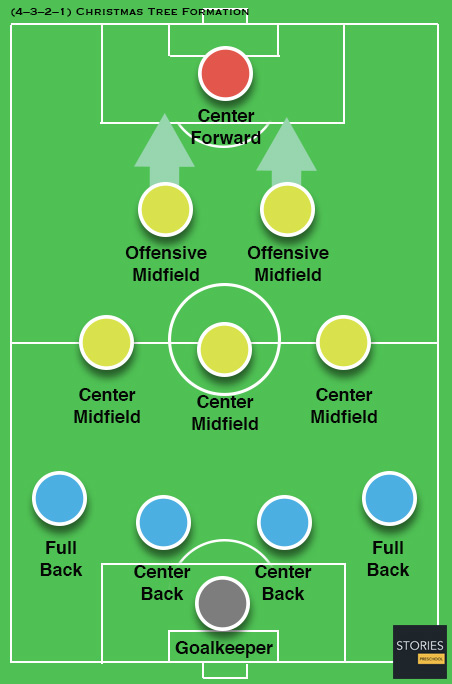

(4–3–2–1) Christmas Tree Formation

The 4–3–2–1, commonly described as the "Christmas Tree" formation, has another forward brought on for a midfielder to play "in the hole", so leaving two forwards slightly behind the most forward striker. View Soccer Formation »

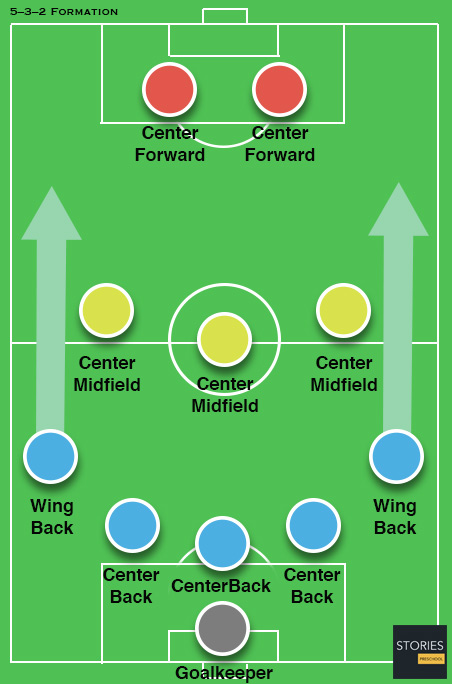

5–3–2 Formation

This formation has three central defenders (possibly with one acting as a sweeper.) This system is heavily reliant on the wing-backs providing width for the team. The two wide full-backs act as wing-backs. It is their job to work their flank along the full length of the pitch, supporting both the defense and the attack. View Soccer Formation »

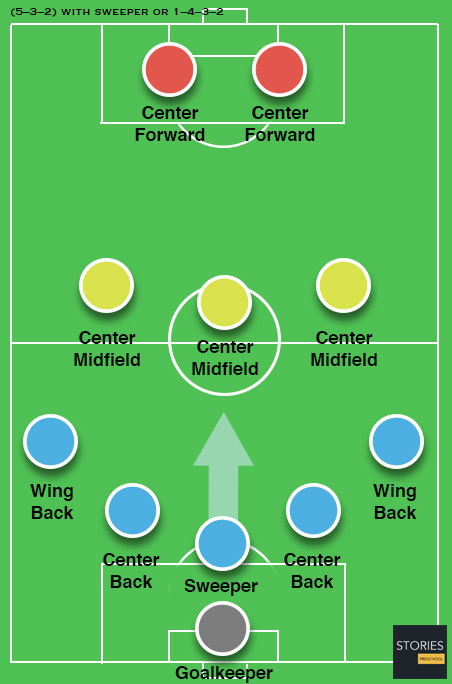

(5–3–2) with sweeper or 1–4–3–2

A variant of the 5–3–2, this involves a more withdrawn sweeper, who may join the midfield, and more advanced full-backs. View Soccer Formation »

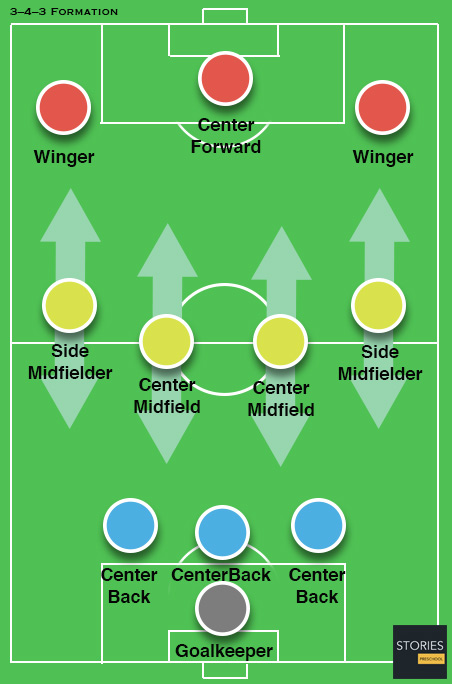

3–4–3 Formation

Using a 3–4–3, the midfielders are expected to split their time between attacking and defending. Having only three dedicated defenders means that if the opposing team breaks through the midfield, they will have a greater chance to score than with a more conventional defensive configuration, such as 4–5–1 or 4–4–2. View Soccer Formation »

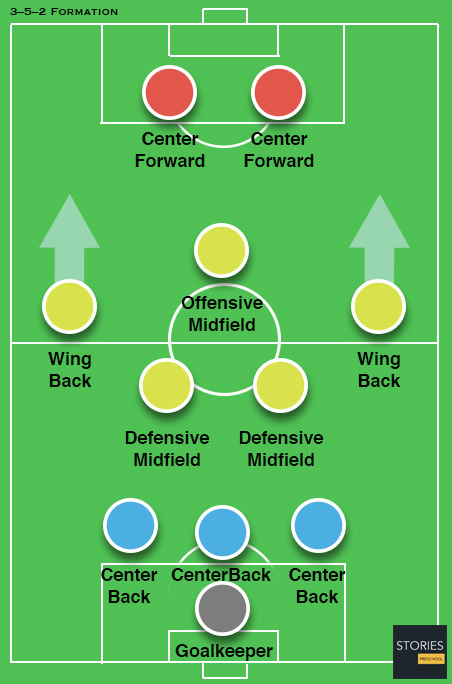

3–5–2 Formation

This formation is similar to 5–3–2 except that the two wingmen are oriented more towards the attack. Because of this, the central midfielder tends to remain further back in order to help prevent counter-attacks. It differs from the classical 3–5–2 of the WW by having a non-staggered midfield. View Soccer Formation »

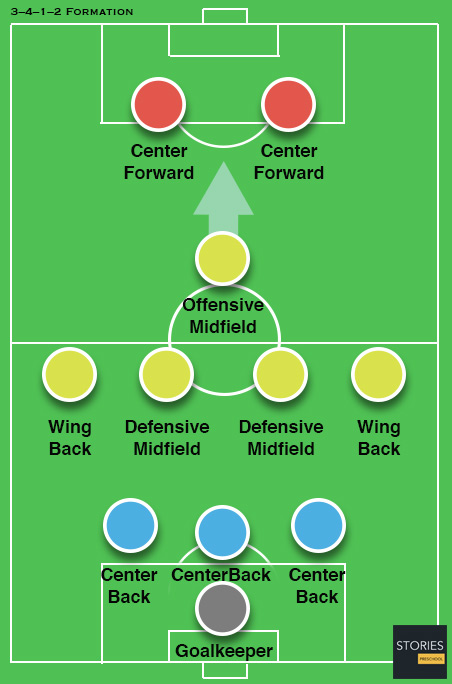

3–4–1–2 Formation

3-4-1-2 is a variant of 3-5-2 where the wingers are more withdrawn in favour of one of the central midfielders being pushed further upfield into the "number 10" playmaker position. Martin O'Neill successfully used this formation during the early years of his reign as Celtic manager, noticeably taking them to the 2003 UEFA Cup Final. View Soccer Formation »

3–6–1 Formation

This uncommon modern formation focuses on ball possession in the midfield. In fact, it is very rare to see it as an initial formation, as it is more useful for maintaining a lead or tie score. Its more common variants are 3–4–2–1 or 3–4–3 diamond, which use two wingbacks. View Soccer Formation »

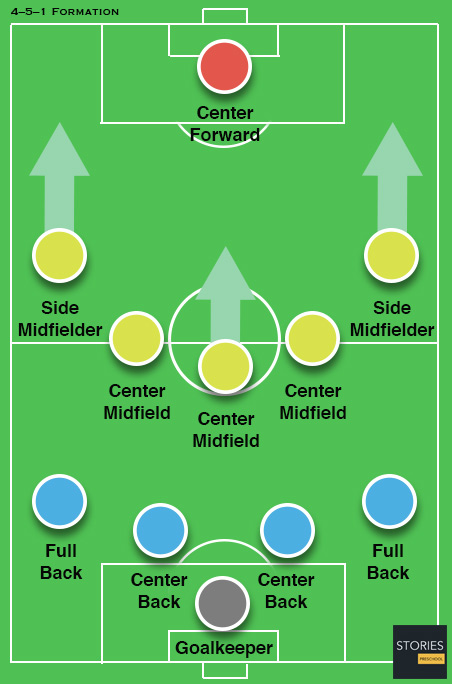

4–5–1 Formation

4–5–1 is a defensive formation; however, if the two midfield wingers play a more attacking role, it can be likened to 4–3–3. The formation can be used to grind out 0–0 draws or preserve a lead, as the packing of the centre midfield makes it difficult for the opposition to build up play. View Soccer Formation »

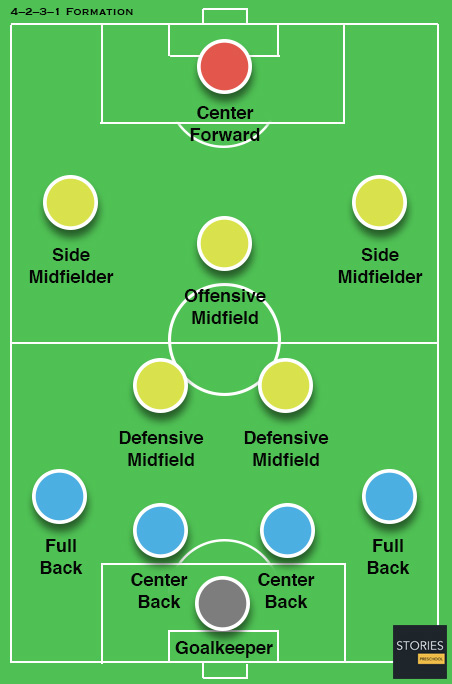

4–2–3–1 Formation

This formation is widely used by Spanish, French and German sides. While it seems defensive to the eye, it is quite a flexible formation, as both the wide players and the full-backs join the attack. In defense, this formation is similar to either the 4–5–1 or 4–4–1–1. It is used to maintain possession of the ball and stopping opponent attacks by controlling the midfield area of the field. View Soccer Formation »

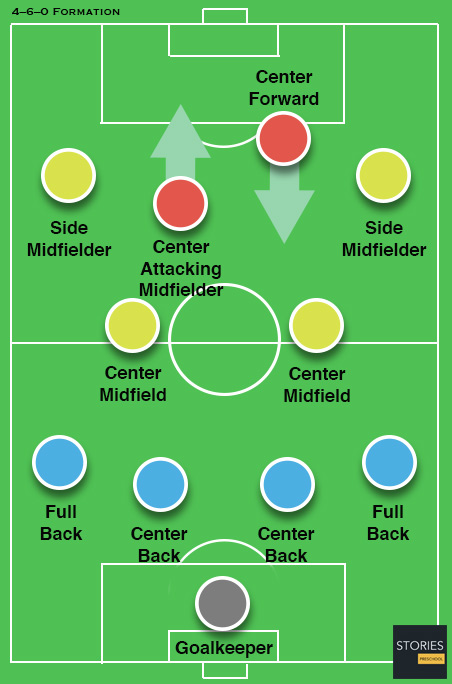

4–6–0 Formation

A highly unconventional formation, the 4–6–0 is an evolution of the 4–2–3–1 in which the centre forward is exchanged for a player who normally plays as a trequartista (that is, in the 'hole'). Suggested as a possible formation for the future of football, the formation sacrifices an out-and-out striker for the tactical advantage of a mobile front four attacking from a position that the opposition defenders cannot mark without being pulled out of position. View Soccer Formation »

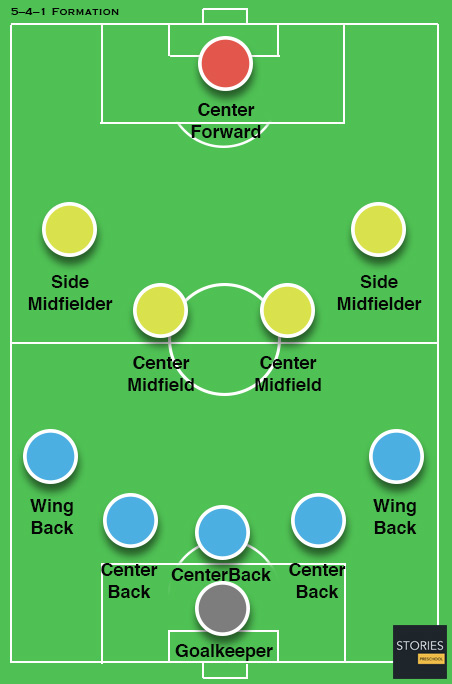

5–4–1 Formation

This is a particularly defensive formation, with an isolated forward and a packed defense. Again, however, a couple of attacking full-backs can make this formation resemble something like a 3–6–1. One of the most famous cases of its use is the UEFA 2004 European Championship winning Greek national team. View Soccer Formation »

1–6–3 Formation

The 1–6–3 formation was first utilized by Japan at the behest of General Yoshijirō Umezu in 1936. Famously, Japan defeated the heavily favoured Swedish team 3–2 at the 1936 Olympics with the unorthodox 1–6–3 formation, before going down 0–8 to Italy. The formation was dubbed the "kamikaze" formation. View Soccer Formation »

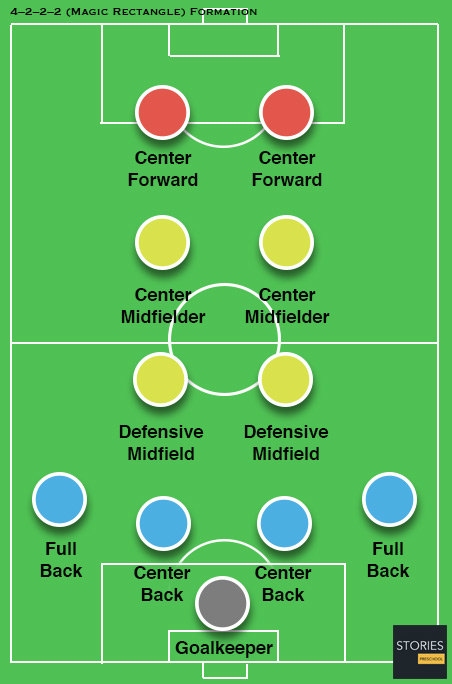

4–2–2–2 (Magic Rectangle) Formation

The "Magic Rectangle" is formed by combining two box-to-box midfielders with two deep-lying ("hanging") forwards across the midfield. This provides a balance in the distribution of possible moves and adds a dynamic quality to midfield play. View Soccer Formation »

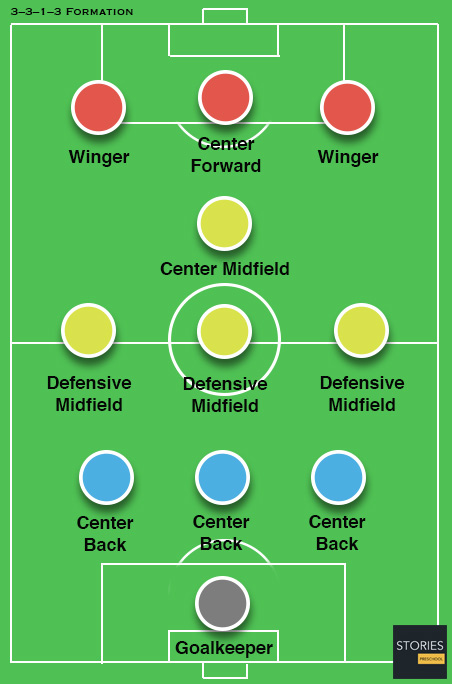

3–3–1–3 Formation

The 3–3–1–3 was formed of a modification to the Dutch 4–3–3 system Ajax had developed. Coaches like Louis van Gaal and Johan Cruyff brought it to even further attacking extremes and the system eventually found its way to Barcelona, where players such as Andrés Iniesta and Xavi were reared into 3–3–1–3's philosophy. View Soccer Formation »

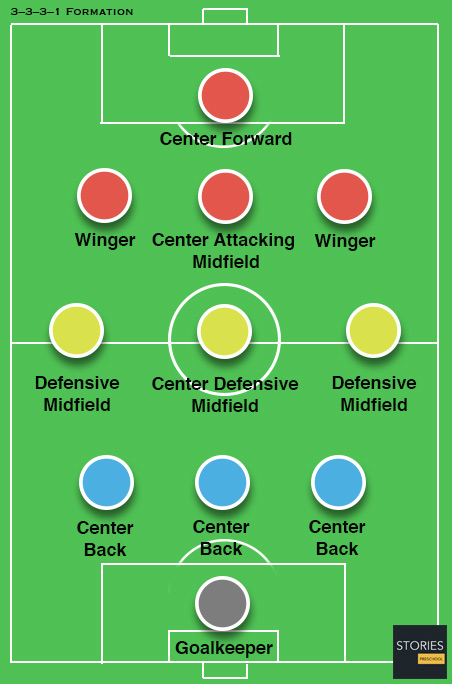

3–3–3–1 Formation

The 3–3–3–1 system is a very attacking formation and its compact nature is ideally suited for midfield domination and ball possession. It means a coach can field more attacking players and add extra strength through the spine of the team. The attacking three are usually two wing-backs or wingers with the central player of the three occupying a central attacking midfield. View Soccer Formation »

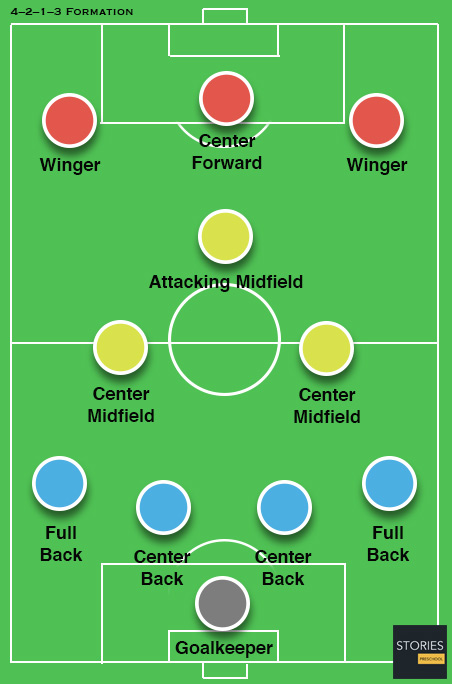

4–2–1–3 Formation

The somewhat unconventional 4–2–1–3 formation was developed by José Mourinho during his time at Internazionale including in the 2010 UEFA Champions League Final. By using captain Javier Zanetti and Esteban Cambiasso in holding midfield positions, he was able to push more players to attack. View Soccer Formation »

Incomplete Formations

When a player is sent off (ex. after being shown a red card) or leaves the field due to an injury or other reason with no ability to be replaced with a substitute teams generally fall back to defensive formations such as 4–4–1 or 5–3–1. Only when facing a negative result will a team with ten players play in a risky attacking formation such as 4–3–2 or even 4–2–3.

SPORTS

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles "Association football" and "Formation (Association football)", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.