Vietnam War (1955–1975)

Johnson's Escalation, 1963–69

At the time Lyndon B. Johnson took over the presidency after the death of Kennedy, he had not been heavily involved with policy toward Vietnam, Presidential aide Jack Valenti recalls, "Vietnam at the time was no bigger than a man's fist on the horizon. We hardly discussed it because it was not worth discussing."

Upon becoming president, however, Johnson immediately had to focus on Vietnam: on 24 November 1963, he said, "the battle against communism ... must be joined ... with strength and determination." The pledge came at a time when the situation in South Vietnam was deteriorating, especially in places like the Mekong Delta, because of the recent coup against Diệm. However, Johnson knew that he had inherited a rapidly deteriorating situation in South Vietnam, believing in the widely accepted arguments that were used for defending the South: Should they retreat or appease, either action would imperil other nations beyond the conflict.

The military revolutionary council, meeting in lieu of a strong South Vietnamese leader, was made up of 12 members headed by General Dương Văn Minh—whom Stanley Karnow, a journalist on the ground, later recalled as "a model of lethargy". Lodge, frustrated by the end of the year, cabled home about Minh: "Will he be strong enough to get on top of things?" His regime was overthrown in January 1964 by General Nguyễn Khánh. However, there was persistent instability in the military as several coups—not all successful—occurred in a short period of time.

On 2 August 1964, the USS Maddox, on an intelligence mission along North Vietnam's coast, allegedly fired upon and damaged several torpedo boats that had been stalking it in the Gulf of Tonkin. A second attack was reported two days later on the USS Turner Joy and Maddox in the same area. The circumstances of the attack were murky. Lyndon Johnson commented to Undersecretary of State George Ball that "those sailors out there may have been shooting at flying fish."

The second attack led to retaliatory air strikes, prompted Congress to approve the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on 7 August 1964, signed by Johnson, and gave the president power to conduct military operations in Southeast Asia without declaring war. Although Congressmen at the time denied that this was a full-scale war declaration, the Tonkin Resolution allowed the president unilateral power to launch a full-scale war if the president deemed it necessary. In the same month, Johnson pledged that he was not "committing American boys to fighting a war that I think ought to be fought by the boys of Asia to help protect their own land".

An undated NSA publication declassified in 2005, however, revealed that there was no attack on 4 August. It had already been called into question long before this. "The Gulf of Tonkin incident", wrote Louise Gerdes, "is an oft-cited example of the way in which Johnson misled the American people to gain support for his foreign policy in Vietnam." George C. Herring argues, however, that McNamara and the Pentagon "did not knowingly lie about the alleged attacks, but they were obviously in a mood to retaliate and they seem to have selected from the evidence available to them those parts that confirmed what they wanted to believe."

"From a strength of approximately 5,000 at the start of 1959 the Viet Cong's ranks grew to about 100,000 at the end of 1964 ... Between 1961 and 1964 the Army's strength rose from about 850,000 to nearly a million men." The numbers for U.S. troops deployed to Vietnam during the same period were quite different; 2,000 in 1961, rising rapidly to 16,500 in 1964. By early 1965, 7,559 South Vietnamese hamlets had been destroyed by the Viet Cong.

The National Security Council recommended a three-stage escalation of the bombing of North Vietnam. On 7 February 1965 following an attack on a U.S. Army base in Pleiku, Operation Flaming Dart (initiated when Soviet Soviet Union, officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. The Soviet Union fall process began with growing unrest in the Union's various constituent national republics developing into an incessant political and legislative conflict between them and the central government. Estonia was the first Soviet republic to declare state sovereignty inside the Union. Premier Alexei Kosygin was on a state visit to North Vietnam), Operation Rolling Thunder and Operation Arc Light commenced. The bombing campaign, which ultimately lasted three years, was intended to force North Vietnam to cease its support for the Viet Cong by threatening to destroy North Vietnam's air defenses and industrial infrastructure. As well, it was aimed at bolstering the morale of the South Vietnamese. Between March 1965 and November 1968, "Rolling Thunder" deluged the north with a million tons of missiles, rockets and bombs.

Soviet Union, officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. The Soviet Union fall process began with growing unrest in the Union's various constituent national republics developing into an incessant political and legislative conflict between them and the central government. Estonia was the first Soviet republic to declare state sovereignty inside the Union. Premier Alexei Kosygin was on a state visit to North Vietnam), Operation Rolling Thunder and Operation Arc Light commenced. The bombing campaign, which ultimately lasted three years, was intended to force North Vietnam to cease its support for the Viet Cong by threatening to destroy North Vietnam's air defenses and industrial infrastructure. As well, it was aimed at bolstering the morale of the South Vietnamese. Between March 1965 and November 1968, "Rolling Thunder" deluged the north with a million tons of missiles, rockets and bombs.

These books are available for download with Apple Books on your Mac or iOS device

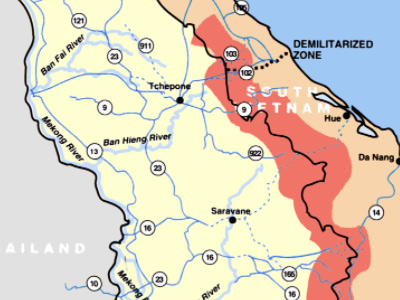

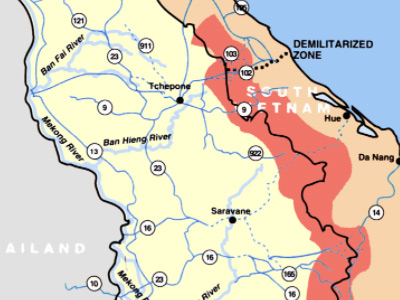

Bombing was not restricted to North Vietnam. Other aerial campaigns, such as Operation Commando Hunt, targeted different parts of the Viet Cong and NVA infrastructure. These included the Ho Chi Minh trail supply route, which ran through Laos and Cambodia. The objective of stopping North Vietnam and the Viet Cong was never reached. As Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Vann noted, "This is a political war and it calls for discriminate killing. The best weapon ... would be a knife ... The worst is an airplane." The Chief of Staff of the United States The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, D.C., and the most populous city and financial center is New York City. Air Force Curtis LeMay, however, had long advocated saturation bombing in Vietnam and wrote of the communists that "we're going to bomb them back into the Stone Age".

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, D.C., and the most populous city and financial center is New York City. Air Force Curtis LeMay, however, had long advocated saturation bombing in Vietnam and wrote of the communists that "we're going to bomb them back into the Stone Age".

Escalation and Ground War

After several attacks upon them, it was decided that U.S. Air Force bases needed more protection as the South Vietnamese military seemed incapable of providing security. On 8 March 1965, 3,500 U.S. Marines were dispatched to South Vietnam. This marked the beginning of the American ground war. U.S. public opinion overwhelmingly supported the deployment.

In a statement similar to that made to the French France, officially the French Republic is transcontinental country predominantly located in Western Europe and spanning overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. France reached its political and military zenith in the early 19th century under Napoleon Bonaparte, subjugating much of continental Europe and establishing the First French Empire. almost two decades earlier, Ho Chi Minh warned that if the Americans "want to make war for twenty years then we shall make war for twenty years. If they want to make peace, we shall make peace and invite them to afternoon tea." Some have argued that the policy of North Vietnam was not to topple other non-communist governments in South East Asia.

France, officially the French Republic is transcontinental country predominantly located in Western Europe and spanning overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. France reached its political and military zenith in the early 19th century under Napoleon Bonaparte, subjugating much of continental Europe and establishing the First French Empire. almost two decades earlier, Ho Chi Minh warned that if the Americans "want to make war for twenty years then we shall make war for twenty years. If they want to make peace, we shall make peace and invite them to afternoon tea." Some have argued that the policy of North Vietnam was not to topple other non-communist governments in South East Asia.

The Marines' initial assignment was defensive. The first deployment of 3,500 in March 1965 was increased to nearly 200,000 by December. The U.S. military had long been schooled in offensive warfare. Regardless of political policies, U.S. commanders were institutionally and psychologically unsuited to a defensive mission. In December 1964, ARVN forces had suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Bình Giã, in a battle that both sides viewed as a watershed. Previously, communist forces had utilized hit-and-run guerrilla tactics. However, at Binh Gia, they had defeated a strong ARVN force in a conventional battle. Tellingly, South Vietnamese forces were again defeated in June 1965 at the Battle of Đồng Xoài.

Desertion rates were increasing, and morale plummeted. General William Westmoreland informed Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp Jr., commander of U.S. Pacific forces, that the situation was critical. He said, "I am convinced that U.S. troops with their energy, mobility, and firepower can successfully take the fight to the NLF [National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam a.k.a. the Viet Cong]". With this recommendation, Westmoreland was advocating an aggressive departure from America's defensive posture and the sidelining of the South Vietnamese. By ignoring ARVN units, the U.S. commitment became open-ended. Westmoreland outlined a three-point plan to win the war:

- Phase 1. Commitment of U.S. (and other free world) forces necessary to halt the losing trend by the end of 1965.

- Phase 2. U.S. and allied forces mount major offensive actions to seize the initiative to destroy guerrilla and organized enemy forces. This phase would end when the enemy had been worn down, thrown on the defensive, and driven back from major populated areas.

- Phase 3. If the enemy persisted, a period of twelve to eighteen months following Phase 2 would be required for the final destruction of enemy forces remaining in remote base areas

The plan was approved by Johnson and marked a profound departure from the previous administration's insistence that the government of South Vietnam was responsible for defeating the guerrillas. Westmoreland predicted victory by the end of 1967. Johnson did not, however, communicate this change in strategy to the media. Instead he emphasized continuity. The change in U.S. policy depended on matching the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong in a contest of attrition and morale. The opponents were locked in a cycle of escalation. The idea that the government of South Vietnam could manage its own affairs was shelved.

The one-year tour of duty of American soldiers deprived units of experienced leadership. As one observer noted "we were not in Vietnam for 10 years, but for one year 10 times." As a result, training programs were shortened.

South Vietnam was inundated with manufactured goods. As Stanley Karnow writes, "the main PX [Post Exchange], located in the Saigon suburb of Cholon, was only slightly smaller than the New York Bloomingdale's ..." The American buildup transformed the economy and had a profound effect on South Vietnamese society. A huge surge in corruption was witnessed.

Washington encouraged its SEATO allies to contribute troops. Australia Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. In 1770, the British explorer James Cook mapped and claimed the east coast of Australia for Great Britain, and the First British Fleet arrived in 1788 to establish the penal colony of New South Wales. Australia sent many thousands of troops to fight for Britain during WWI., New Zealand

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. In 1770, the British explorer James Cook mapped and claimed the east coast of Australia for Great Britain, and the First British Fleet arrived in 1788 to establish the penal colony of New South Wales. Australia sent many thousands of troops to fight for Britain during WWI., New Zealand New Zealand is an island country in southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses - the North Island and the South Island - and over 700 smaller islands. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire. Subsequently, a series of conflicts between the colonial government and Māori tribes resulted in the alienation and confiscation of large amounts of Māori land. Reflecting this, New Zealand's culture is mainly derived from Māori and early British settlers., South Korea

New Zealand is an island country in southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses - the North Island and the South Island - and over 700 smaller islands. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire. Subsequently, a series of conflicts between the colonial government and Māori tribes resulted in the alienation and confiscation of large amounts of Māori land. Reflecting this, New Zealand's culture is mainly derived from Māori and early British settlers., South Korea South Korea officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Since the 21st century, South Korea has been renowned for its globally influential pop culture, particularly in music (K-pop), TV dramas (K-dramas) and cinema, a phenomenon referred to as the Korean wave., Thailand, and the Philippines all agreed to send troops. Major allies, however, notably NATO

South Korea officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Since the 21st century, South Korea has been renowned for its globally influential pop culture, particularly in music (K-pop), TV dramas (K-dramas) and cinema, a phenomenon referred to as the Korean wave., Thailand, and the Philippines all agreed to send troops. Major allies, however, notably NATO The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is an intergovernmental transnational military alliance. Established in the aftermath of World War II, the organization implements the North Atlantic Treaty, signed in Washington, DC, on 4 April 1949. NATO is a collective security system: its independent member states agree to defend each other against attacks by third parties. During the Cold War, NATO operated as a check on the threat posed by the Soviet Union. nations Canada and the United Kingdom, declined Washington's troop requests. The U.S. and its allies mounted complex operations, such as operations Masher, Attleboro, Cedar Falls, and Junction City. However, the communist insurgents remained elusive and demonstrated great tactical flexibility.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is an intergovernmental transnational military alliance. Established in the aftermath of World War II, the organization implements the North Atlantic Treaty, signed in Washington, DC, on 4 April 1949. NATO is a collective security system: its independent member states agree to defend each other against attacks by third parties. During the Cold War, NATO operated as a check on the threat posed by the Soviet Union. nations Canada and the United Kingdom, declined Washington's troop requests. The U.S. and its allies mounted complex operations, such as operations Masher, Attleboro, Cedar Falls, and Junction City. However, the communist insurgents remained elusive and demonstrated great tactical flexibility.

Meanwhile, the political situation in South Vietnam began to stabilize with the coming to power of prime minister Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and figurehead Chief of State, General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, in mid-1965 at the head of a military junta. This ended a series of coups that had happened more than once a year. In 1967, Thieu became president with Ky as his deputy, after rigged elections. Although they were nominally a civilian government, Ky was supposed to maintain real power through a behind-the-scenes military body. However, Thieu outmaneuvered and sidelined Ky by filling the ranks with generals from his faction. Thieu was also accused of murdering Ky loyalists through contrived military accidents. Thieu, mistrustful and indecisive, remained president until 1975, having won a one-candidate election in 1971.

The Johnson administration employed a "policy of minimum candor" in its dealings with the media. Military information officers sought to manage media coverage by emphasizing stories that portrayed progress in the war. Over time, this policy damaged the public trust in official pronouncements. As the media's coverage of the war and that of the Pentagon diverged, a so-called credibility gap developed.

Tet Offensive

In late 1967 the Communists lured American forces into the hinterlands at Đắk Tô and at the Marine Khe Sanh combat base in Quảng Trị Province where the United States was more than willing to fight because it could unleash its massive firepower unimpeded by civilians. However, on 30 January 1968, the NVA and the Viet Cong broke the truce that traditionally accompanied the Tết (Lunar New Year) holiday by launching the largest battle of the war, the Tet Offensive, in the hope of sparking a national uprising. Over 100 cities were attacked by over 85,000 enemy troops including assaults on General Westmoreland's headquarters and the U.S. Embassy in Saigon.

Although the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces were initially shocked by the scale of the urban offensive, they responded quickly and effectively, decimating the ranks of the Viet Cong. In the former capital city of Huế, the combined NVA and Viet Cong troops captured the Imperial Citadel and much of the city and massacred over 3,000 unarmed Huế civilians. In the following Battle of Huế American forces employed massive firepower that left 80 percent of the city in ruins. Further north, at Quảng Trị City, members of the 1st Cavalry Division and 1st ARVN Infantry Division killed more than 900 NVA and Vietcong troops in and around the city. In Saigon, 1,000 NLF (Viet Cong) fighters fought off 11,000 U.S. and ARVN troops for three weeks.

Across South Vietnam, 1,100 Americans and other allied troops, 2,100 ARVN, 14,000 civilians, and 32,000 NVA and Viet Cong lay dead.

But the Tet Offensive had another, unintended consequence. General Westmoreland had become the public face of the war. He had been named Time magazine's 1965's Man of the Year and eventually was featured on the magazine's cover three times. Time described him as "the sinewy personification of the American fighting man ... [who] directed the historic buildup, drew up the battle plans, and infused the… men under him with his own idealistic view of U.S. aims and responsibilities." Six weeks after the Tet Offensive began, "public approval of his overall performance dropped from 48 percent to 36 percent–and, more dramatically, endorsement for his handling of the war fell from 40 percent to 26 percent."

A few months earlier, in November 1967, Westmoreland had spearheaded a public relations drive for the Johnson administration to bolster flagging public support. In a speech before the National Press Club he had said a point in the war had been reached "where the end comes into view." Thus, the public was shocked and confused when Westmoreland's predictions were trumped by Tet. The American media, which had until then been largely supportive of U.S. efforts, turned on the Johnson administration for what had become an increasing credibility gap.

Although the Tet Offensive was a significant victory for allied forces, in terms of casualties and control of territory, it was a sound defeat when evaluated from the point of view of strategic consequences: it became a turning point in America's involvement in the Vietnam War because it had a profound impact on domestic support for the conflict. Despite the military failure for the Communist forces, the Tet Offensive became a political victory for them and ended the career of president Lyndon B. Johnson, who declined to run for re-election as his approval rating slumped from 48 to 36 percent. As James Witz noted, Tet "contradicted the claims of progress ... made by the Johnson administration and the military". The offensive constituted an intelligence failure on the scale of Pearl Harbor. Journalist Peter Arnett, in a disputed article, quoted an officer he refused to identify, saying of Bến Tre (laid to rubble by U.S. attacks) that "it became necessary to destroy the village in order to save it".

Walter Cronkite said in an editorial, "To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion." Following Cronkite's editorial report, President Lyndon Johnson is reported to have said, "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America." Whether this statement was actually made by Johnson has been called into doubt.

Westmoreland became Chief of Staff of the Army in March 1968, just as all resistance was finally subdued. The move was technically a promotion. However, his position had become untenable because of the offensive and because his request for 200,000 additional troops had been leaked to the media. Westmoreland was succeeded by his deputy Creighton Abrams, a commander less inclined to public media pronouncements.

On 10 May 1968, despite low expectations, peace talks began between the United States and North Vietnam in Paris. Negotiations stagnated for five months, until Johnson gave orders to halt the bombing of North Vietnam.

As historian Robert Dallek writes, "Lyndon Johnson's escalation of the war in Vietnam divided Americans into warring camps ... cost 30,000 American lives by the time he left office, [and] destroyed Johnson's presidency ..." His refusal to send more U.S. troops to Vietnam was seen as Johnson's admission that the war was lost. In effect, Johnson found that the Vietnam War was no easier to prosecute than the Korean war, learning from experience that China was likely to intervene directly if Hanoi's survival was threatened. Likewise, the Soviet Union would respond by providing more supplies and equipment to raise the cost for U.S. involvement, weakening their defenses in Europe and in the worse case trigger a nuclear confrontation. It can be seen that the refusal was a tacit admission that the war could not be won by escalation, at least not at a cost acceptable to the American people. As Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara noted, "the dangerous illusion of victory by the United States was therefore dead."

Vietnam was a major political issue during the United States presidential election in 1968. The election was won by Republican party candidate Richard Nixon.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Vietnam War (1955–1975)", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.