Vietnam War (1955–1975)

Exit of the Americans: 1973–75

The United States began drastically reducing their troop support in South Vietnam during the final years of Vietnamization. Many U.S. troops were removed from the region, and on 5 March 1971, the United States returned the 5th Special Forces Group, which was the first American unit deployed to South Vietnam, to its former base in Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Under the Paris Peace Accords, between North Vietnamese Foreign Minister Lê Đức Thọ and U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and reluctantly signed by South Vietnamese president Thiệu, United States The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, D.C., and the most populous city and financial center is New York City. military forces withdrew from South Vietnam and prisoners were exchanged. North Vietnam was allowed to continue supplying communist troops in the South, but only to the extent of replacing expended materiel. Later that year the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Kissinger and Thọ, but the Vietnamese negotiator declined it saying that a true peace did not yet exist.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country in North America. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. The United States shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south. The national capital is Washington, D.C., and the most populous city and financial center is New York City. military forces withdrew from South Vietnam and prisoners were exchanged. North Vietnam was allowed to continue supplying communist troops in the South, but only to the extent of replacing expended materiel. Later that year the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Kissinger and Thọ, but the Vietnamese negotiator declined it saying that a true peace did not yet exist.

The communist leaders had expected that the ceasefire terms would favor their side. But Saigon, bolstered by a surge of U.S. aid received just before the ceasefire went into effect, began to roll back the Viet Cong. The communists responded with a new strategy hammered out in a series of meetings in Hanoi in March 1973, according to the memoirs of Trần Văn Trà.

As the Viet Cong's top commander, Tra participated in several of these meetings. With U.S. bombings suspended, work on the Ho Chi Minh trail and other logistical structures could proceed unimpeded. Logistics would be upgraded until the North was in a position to launch a massive invasion of the South, projected for the 1975–76 dry season. Tra calculated that this date would be Hanoi's last opportunity to strike before Saigon's army could be fully trained.

In the November 1972 Election, Democratic nominee George McGovern lost 49 of 50 states to the incumbent President Richard Nixon. On 15 March 1973, President Nixon implied that the United States would intervene militarily if the communist side violated the ceasefire. Public and congressional reaction to Nixon's trial balloon was unfavorable and in April Nixon appointed Graham Martin as U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam. During his confirmation hearings in June 1973, Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger stated that he would recommend resumption of U.S. bombing in North Vietnam if North Vietnam launched a major offensive against South Vietnam. On 4 June 1973, the U.S. Senate passed the Case–Church Amendment to prohibit such intervention.

The oil price shock of October 1973 following the Yom Kippur War in Egypt caused significant damage to the South Vietnamese economy. The Viet Cong resumed offensive operations when the dry season began and by January 1974 it had recaptured the territory it lost during the previous dry season. After two clashes that left 55 South Vietnamese soldiers dead, President Thieu announced on 4 January that the war had restarted and that the Paris Peace Accord was no longer in effect. There had been over 25,000 South Vietnamese casualties during the ceasefire period.

Gerald Ford took over as U.S. president on 9 August 1974 after President Nixon resigned due to the Watergate scandal. At this time, Congress cut financial aid to South Vietnam from $1 billion a year to $700 million. The U.S. midterm elections in 1974 brought in a new Congress dominated by Democrats who were even more determined to confront the president on the war. Congress immediately voted in restrictions on funding and military activities to be phased in through 1975 and to culminate in a total cutoff of funding in 1976.

The success of the 1973–74 dry season offensive inspired Trà to return to Hanoi in October 1974 and plead for a larger offensive in the next dry season. This time, Trà could travel on a drivable highway with regular fueling stops, a vast change from the days when the Ho Chi Minh trail was a dangerous mountain trek. Giáp, the North Vietnamese defense minister, was reluctant to approve Trà's plan. A larger offensive might provoke a U.S. reaction and interfere with the big push planned for 1976. Trà appealed over Giáp's head to first secretary Lê Duẩn, who approved of the operation.

Trà's plan called for a limited offensive from Cambodia into Phước Long Province. The strike was designed to solve local logistical problems, gauge the reaction of South Vietnamese forces, and determine whether U.S. would return to the fray.

On 13 December 1974, North Vietnamese forces attacked Route 14 in Phước Long Province. Phuoc Binh, the provincial capital, fell on 6 January 1975. Ford desperately asked Congress for funds to assist and re-supply the South before it was overrun. Congress refused. The fall of Phuoc Binh and the lack of an American response left the South Vietnamese elite demoralized.

The speed of this success led the Politburo to reassess its strategy. It was decided that operations in the Central Highlands would be turned over to General Văn Tiến Dũng and that Pleiku should be seized, if possible. Before he left for the South, Dũng was addressed by Lê Duẩn: "Never have we had military and political conditions so perfect or a strategic advantage as great as we have now."

At the start of 1975, the South Vietnamese had three times as much artillery and twice the number of tanks and armored cars as the opposition. They also had 1,400 aircraft and a two-to-one numerical superiority in combat troops over their Communist enemies. However, the rising oil prices meant that much of this could not be used. They faced a well-organized, highly determined and well-funded North Vietnam. Much of the North's material and financial support came from the communist bloc. Within South Vietnam, there was increasing chaos. The departure of the American military had compromised an economy dependent on U.S. financial support and the presence of a large number of U.S. troops. South Vietnam suffered from the global recession that followed the Arab oil embargo.

Campaign 275

On 10 March 1975, General Dung launched Campaign 275, a limited offensive into the Central Highlands, supported by tanks and heavy artillery. The target was Buôn Ma Thuột, in Đắk Lắk Province. If the town could be taken, the provincial capital of Pleiku and the road to the coast would be exposed for a planned campaign in 1976. The ARVN proved incapable of resisting the onslaught, and its forces collapsed on 11 March. Once again, Hanoi was surprised by the speed of their success. Dung now urged the Politburo to allow him to seize Pleiku immediately and then turn his attention to Kon Tum. He argued that with two months of good weather remaining until the onset of the monsoon, it would be irresponsible to not take advantage of the situation.

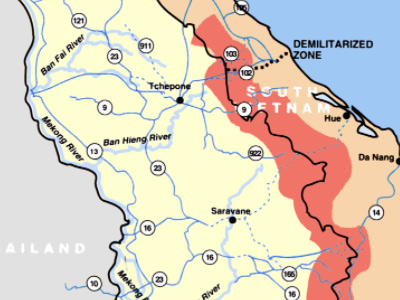

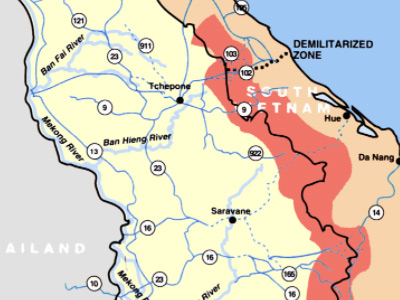

President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, a former general, was fearful that his forces would be cut off in the north by the attacking communists; Thieu ordered a retreat. The president declared this to be a "lighten the top and keep the bottom" strategy. But in what appeared to be a repeat of Operation Lam Son 719, the withdrawal soon turned into a bloody rout. While the bulk of ARVN forces attempted to flee, isolated units fought desperately. ARVN General Phu abandoned Pleiku and Kon Tum and retreated toward the coast, in what became known as the "column of tears".

As the ARVN tried to disengage from the enemy, refugees mixed in with the line of retreat. The poor condition of roads and bridges, damaged by years of conflict and neglect, slowed Phu's column. As the North Vietnamese forces approached, panic set in. Often abandoned by the officers, the soldiers and civilians were shelled incessantly. The retreat degenerated into a desperate scramble for the coast. By 1 April the "column of tears" was all but annihilated.

On 20 March, Thieu reversed himself and ordered Huế, Vietnam's third-largest city, be held at all costs, and then changed his policy several times. Thieu's contradictory orders confused and demoralized his officer corps. As the North Vietnamese launched their attack, panic set in, and ARVN resistance withered. On 22 March, the NVA opened the siege of Huế. Civilians flooded the airport and the docks hoping for any mode of escape. Some even swam out to sea to reach boats and barges anchored offshore. In the confusion, routed ARVN soldiers fired on civilians to make way for their retreat.

On 25 March, after a three-day battle, Huế fell. As resistance in Huế collapsed, North Vietnamese rockets rained down on Da Nang and its airport. By 28 March 35,000 VPA troops were poised to attack the suburbs. By 30 March 100,000 leaderless ARVN troops surrendered as the NVA marched victoriously through Da Nang. With the fall of the city, the defense of the Central Highlands and Northern provinces came to an end.

Final North Vietnamese Offensive

With the northern half of the country under their control, the Politburo ordered General Dung to launch the final offensive against Saigon. The operational plan for the Ho Chi Minh Campaign called for the capture of Saigon before 1 May. Hanoi wished to avoid the coming monsoon and prevent any redeployment of ARVN forces defending the capital. Northern forces, their morale boosted by their recent victories, rolled on, taking Nha Trang, Cam Ranh, and Da Lat.

On 7 April, three North Vietnamese divisions attacked Xuân Lộc, 40 miles (64 km) east of Saigon. The North Vietnamese met fierce resistance at Xuân Lộc from the ARVN 18th Division, who were outnumbered six to one. For two bloody weeks, severe fighting raged as the ARVN defenders made a last stand to try to block the North Vietnamese advance. By 21 April, however, the exhausted garrison were ordered to withdraw towards Saigon.

An embittered and tearful president Thieu resigned on the same day, declaring that the United States had betrayed South Vietnam. In a scathing attack, he suggested U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had tricked him into signing the Paris peace agreement two years earlier, promising military aid that failed to materialize. Having transferred power to Trần Văn Hương, he left for Taiwan on 25 April. At the same time, North Vietnamese tanks had reached Biên Hòa and turned toward Saigon, brushing aside isolated ARVN units along the way.

By the end of April, the ARVN had collapsed on all fronts except in the Mekong Delta. Thousands of refugees streamed southward, ahead of the main communist onslaught. On 27 April 100,000 North Vietnamese troops encircled Saigon. The city was defended by about 30,000 ARVN troops. To hasten a collapse and foment panic, the NVA shelled the airport and forced its closure. With the air exit closed, large numbers of civilians found that they had no way out.

Fall of Saigon

Chaos, unrest, and panic broke out as hysterical South Vietnamese officials and civilians scrambled to leave Saigon. Martial law was declared. American helicopters began evacuating South Vietnamese, U.S., and foreign nationals from various parts of the city and from the U.S. embassy compound. Operation Frequent Wind had been delayed until the last possible moment, because of U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin's belief that Saigon could be held and that a political settlement could be reached.

Schlesinger announced early in the morning of 29 April 1975 the evacuation from Saigon by helicopter of the last U.S. diplomatic, military, and civilian personnel. Frequent Wind was arguably the largest helicopter evacuation in history. It began on 29 April, in an atmosphere of desperation, as hysterical crowds of Vietnamese vied for limited space. Martin pleaded with Washington to dispatch $700 million in emergency aid to bolster the regime and help it mobilize fresh military reserves. But American public opinion had soured on this conflict.

In the United States, South Vietnam was perceived as doomed. President Gerald Ford had given a televised speech on 23 April, declaring an end to the Vietnam War and all U.S. aid. Frequent Wind continued around the clock, as North Vietnamese tanks breached defenses on the outskirts of Saigon. In the early morning hours of 30 April, the last U.S. Marines evacuated the embassy by helicopter, as civilians swamped the perimeter and poured into the grounds. Many of them had been employed by the Americans and were left to their fate.

On 30 April 1975, NVA troops entered the city of Saigon and quickly overcame all resistance, capturing key buildings and installations. A tank from the 324th Division crashed through the gates of the Independence Palace at 11:30 am local time and the Viet Cong flag was raised above it. President Dương Văn Minh, who had succeeded Huong two days earlier, surrendered.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Vietnam War (1955–1975)", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.